The Fritz X – also known as Ruhrstahl SD 1400 X, PC 1400X, Kramer X-1, and FX 1400 – was a German radio-guided anti-ship missile. It evolved from a previous armor-piercing device, incorporating several technological enhancements that markedly enhanced its effectiveness and precision, resulting in significant early successes. Despite these advancements, the Fritz X had inherent limitations that made it ineffective against Allied aircraft.

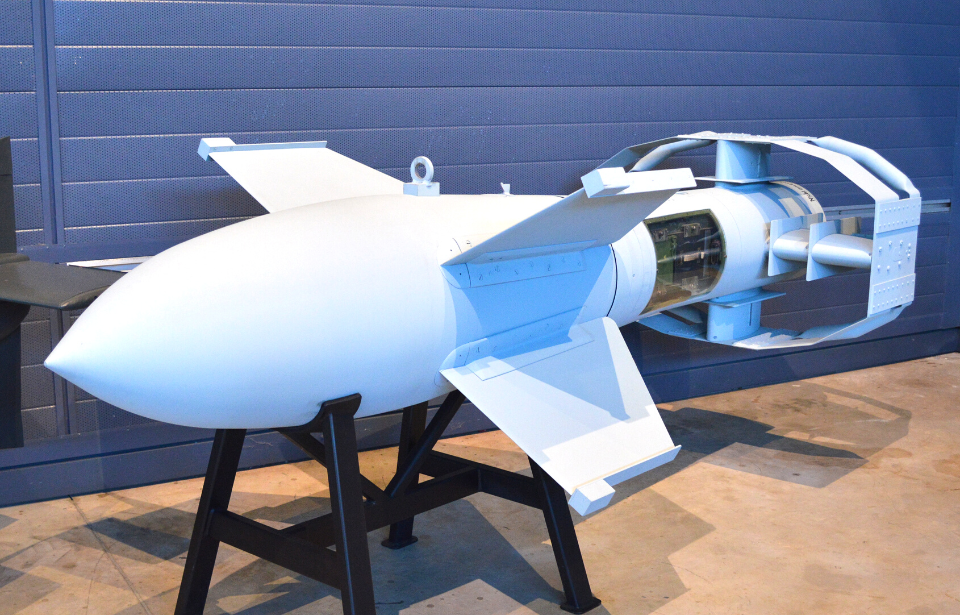

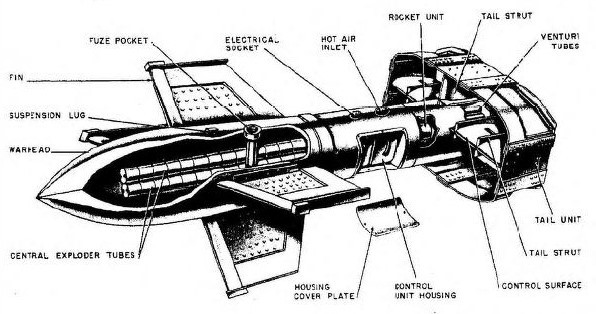

Modified PC 1400

Conceived by Max Kramer and produced by Ruhrstahl AG, the Fritz X originated from the PC 1400 (1,400 kg) bomb. Weighing 3,450 pounds, it carried a 710-pound warhead capable of penetrating up to 28 inches of armor when deployed at an altitude of between 18,000 and 20,000 feet.

In 1940, various versions were crafted to determine the optimal design. The X-2, designed for higher speeds and intended to have an infrared homing device, saw its system abandoned, with only one unit produced. The X-3, which was much larger and heavier, boasted speeds of up to 900 MPH. However, the X-1 emerged as the preferred choice for its simpler operation and development.

By 1941, the Luftwaffe initiated testing of the missile. Two years later, the project progressed to the manufacturing stage.

Fritz X specs

The Fritz X featured improved aerodynamics and was equipped with the Kehl-Strasbourg joystick radio-command system. It boasted an enlarged tail with a 12-sided framework encompassing four streamlined fins, with the two longer fins equipped with spoilers. Two gyros stabilized the explosive, and a pair of wings in an asymmetrical cruciform shape were mounted at the front.

These missiles were launched from Dornier Do 217K-2 and Heinkel He 177A Greif aircraft, with bombardiers using their tail flares to guide them. The radio-controlled spoilers enabled the Fritz X to move as instructed, allowing for remarkable accuracy unless hampered by radio jamming from the Allies.

Success in the Mediterranean Theater

The Fritz X made its debut in combat on July 21, 1943, during a raid on the Port of Augusta in Sicily. At that time, no confirmed hits were reported, and the Allies remained largely unaware of the Germans’ use of radio-guided missiles. However, the Fritz X achieved its most notable success in a subsequent attack on the Italian fleet in September 1943.

Following the arrest of Benito Mussolini, the Italian government entered into negotiations with the Allies. On September 8, the Supreme Allied Command in Europe announced the signing of an armistice. A plan was devised to transfer the Italian naval fleet to Allied ports in Tunisia and Malta. However, the Germans quickly caught wind of the plan and devised their own strategy to intercept the convoy, aiming to prevent the ships from reaching their intended destinations.

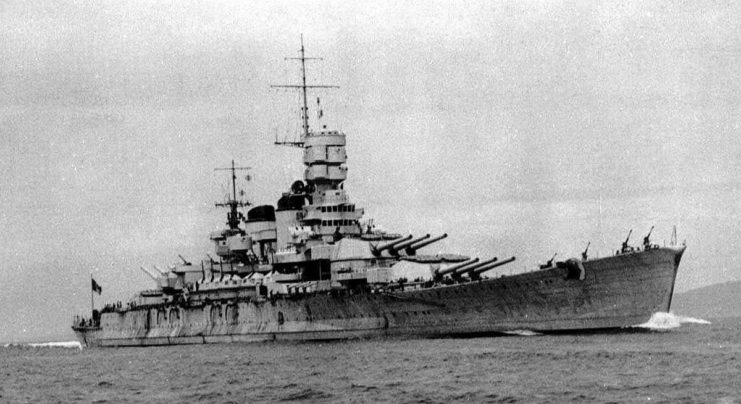

Sinking of Roma (1940)

A squadron consisting of three battleships – Roma (1940), Vittorio Veneto and Italia (1943) – accompanied by six cruisers and eight destroyers, navigated the western coastline of Corsica, making their way toward Sardinia and Tunisia. At midday, six Do 217K-2 aircraft from Gruppe III of Kampfgeschwader 100 Wiking approached the fleet, each carrying a single Fritz X missile.

The most significant success was the sinking of the Italian flagship Roma. A Fritz X missile pierced the battleship’s starboard side, detonating beneath her keel. The resulting explosion inflicted severe damage, flooding Roma‘s boiler and engine rooms while disabling two of her four propeller shafts. This reduction in speed and a series of electrical fires further compounded the crisis.

Merely seven minutes later, another Fritz X found its mark on Roma, this time exploding in her forward engine room and causing a catastrophic magazine detonation. The intensity of the blast claimed the lives of Vice Adm. Carlo Bergamini, the ship’s captain, and 1,393 crew members. Within 30 minutes of the initial strike, Roma split in two and capsized.

In the days following these events, Luftwaffe pilots continued to employ Fritz X missiles, sinking the British cruiser HMS Spartan (95) and destroyer Janus (F53), along with several merchant vessels in the vicinity. They also inflicted substantial damage on the British warship HMS Warspite (03) and cruiser Uganda (66), as well as the American light cruisers USS Philadelphia (CL-41) and Savannah (CL-42).

The Fritz X made German aircraft vulnerable

Although the Fritz X showed promise in the early days, it certainly had its drawbacks. For starters, the bomber aircraft had to fly straight and level while the missile was onboard. Secondly, they had to decelerate immediately following the bombs’ release, as the bombardiers needed a visual to guide them.

Aircraft carrying and deploying the Fritz X soon realized how vulnerable they’d become – and it didn’t take long for the Allies to identify and exploit this.

The most effective defense against Fritz X-carrying German aircraft were fighters, preventing them from flying slow and straight. Additionally, the Allies determined that creating smoke was also effective, as the missiles were less visible and, therefore, caused the bombardiers issues when it came to guiding them. The Allies also quickly set up electronic countermeasures to jam the radio-signals, causing further problems.

More from us: The German V-1 ‘Buzz Bomb’ Was Developed to Terrorize the British Public

The plan initially called for the production of 750 Fritz X missiles per month, but between April 1943 and the end of the program in December the following year, only 1,386 had been produced. Of these, 602 were used in training and testing. On top of that, the missiles weren’t as accurate as the Luftwaffe had hoped, only hitting their targets around 20 percent of the time.

That being said, the Fritz X was the starting point for future spoiler-controlled missile development.