The end of World War II, marked by Japan’s surrender, marked the culmination of a tumultuous and deadly period in human history Even though Germany waved the white flag in May 1945, Japan persisted in its resistance for several additional months. Although some credit Japan’s surrender solely to the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it’s crucial to acknowledge the many factors that played a role.

Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Two pivotal events that contributed to Japan’s surrender were the atomic bombings on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. On the morning of August 6, 1945, the first city was hit, causing widespread destruction and significant loss of life, with between 90,000-146,000 killed both during Little Boy‘s detonation and after, due to radiation exposure and burns to the skin.

Three days later, on August 9, Nagasaki faced a similar attack when the Boeing B-29 Superfortress Bockscar dropped the atomic bomb Fat Man on the city, 261 miles from Hiroshima. Like Hiroshima, Nagasaki suffered immense losses, with an estimated 60,000 to 80,000 people dying within four months of the attack.

Together, these bombings resulted in an estimated death toll of around 129,000 to 226,000 people—a devastating figure.

The atomic bombings underscored the US military’s dominance and marked the beginning of a new and frightening chapter in warfare. The possibility of further nuclear attacks that could obliterate Japanese cities led the Japanese leadership to rethink their stance; the fear of more destruction, along with the realization that conventional defenses were ineffective against such power, played a crucial role in Japan’s decision to surrender.

Declaration of war by the Soviet Union

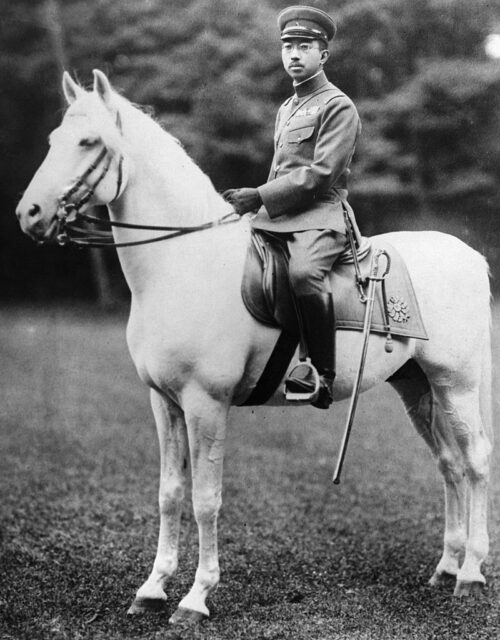

Compounding the despair following the atomic bombings, the Soviet Union’s declaration of war against Japan on August 8, 1945, dealt yet another severe blow to the Japanese military’s hopes. Officials hadn’t believed the Red Army to be much of a threat, with it assumed the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) wouldn’t have to face Joseph Stalin‘s soldiers until Spring 1946. Emperor Hirohito had also previously requested the Soviet dictator act as an intermediary between Japan and the United States.

As a result, the Japanese military and Hirohito were shocked by the sudden Soviet invasion of Manchuria, which saw 650 of the 850 troops occupying the region killed or wounded in the first two days of combat. This declaration of war by the Soviet Union eradicated any hope Japan had for a mediated peace and highlighted the nation’s growing geopolitical isolation.

Faced with the prospect of a two-front war, Japanese leaders recognized the futility of their situation – Hirohito himself even begged military officials to reconsider a surrender.

Japan’s military resources were beginning to dwindle

By 1945, Japan was facing an increasingly difficult situation. Prolonged conflict had significantly weakened its military capabilities, with the United States being primarily responsible. The country’s strategic island-hopping campaign had effectively isolated Japan, cutting off its ties to occupied territories in the Pacific. This isolation was made worse by a strict naval blockade and a relentless aerial bombing campaign targeting Japanese cities and industries, severely hampering the nation’s ability to continue the war.

As a result, there was widespread suffering and hardship among the Japanese population due to the scarcity of essential resources. Food and fuel shortages were severe, leading to an average daily caloric intake of just 1,680 for civilians. Additionally, there was a shortage of working-age males, as many had been enlisted into the military.

The leadership’s decision to surrender was largely influenced by the realization that the war was unwinnable, given the dire state of Japan’s military and resources.

Japan wanted to preserve its Emperor system

One distinctive feature of Japan’s surrender negotiations was the insistence on preserving the emperor system, with the government deeming it a non-negotiable condition. Concerns loomed large over the potential dismantling of the monarchy under unconditional surrender, significantly shaping high-level decision-making.

Eventually, the outcome materialized in the form of the “Humanity Declaration,” in which Hirohito agreed to a “Symbolic” emperor system, rejecting the emperor’s divinity and redefining his role as “the symbol of the State and of the unity of the people.”

This transition meant that while the emperor retained his ceremonial role, he would no longer hold the most political power. Instead, a new constitution would shift power.

Facilitating Japan’s surrender

The process of facilitating Japan’s surrender was marked by significant diplomatic and communicative efforts. Behind the scenes, diplomats and intermediaries worked tirelessly to establish a channel of communication between Japan and the Allied forces. These efforts were aimed at finding a mutually acceptable solution that would allow the country to surrender while addressing the concerns of all parties involved.

With all the aforementioned factors piling on top of the each other, the decision was ultimately made for Japan to surrender, with Emperor Hirohito announcing the news to the public via a radio broadcast on August 15, 1945.

The first time he’d spoken to average citizens directly, the emperor explained, “The war has lasted for nearly four years. Despite the best that has been done by everyone – the gallant fighting of the military and naval forces, the diligence and assiduity of our servants of the state, and the devoted service of our one hundred million people – the war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan’s advantage, while the general trends of the world have turned against her interest.”

More from us: Paul Tibbets Dropped the Atomic Bomb on Hiroshima and Was Given No Funeral or Gravestone

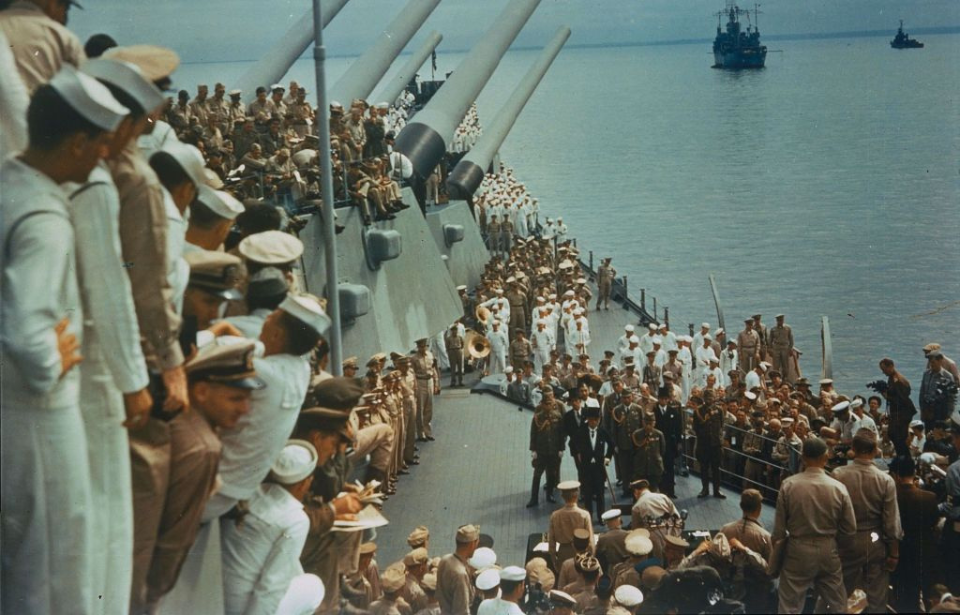

Just over two weeks later, aboard the American battleship USS Missouri (BB-63), the Japanese Instrument of Surrender was signed. Those present included representatives from the Empire of Japan and the Allied nations, with the most notable being Gen. Douglas MacArthur, Fleet Adm. Chester Nimitz and Chief of the Japanese Army General Staff Gen. Yoshijirō Umezu.