As the Second World War progressed, the Allies grew increasingly optimistic about their chances of winning, particularly following their triumph in the Normandy invasion. As a result, the military and political leaders of the countries agreed on the need to create a plan for post-war Germany. Among the various proposals, the Morgenthau Plan stood out as a favored option.

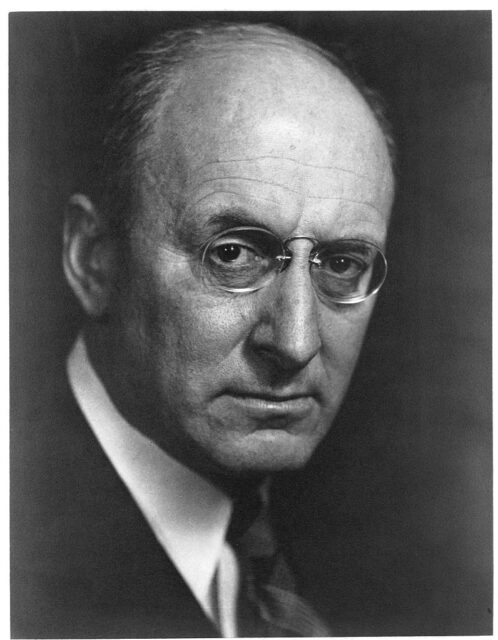

Henry Morgenthau Jr.

The plan was the brainchild of Henry Morgenthau Jr., who acted as secretary of the treasury during Franklin D. Roosevelt‘s presidency from 1934-onward. He was appointed because he was known to be strict with government spending.

When the Second World War began, Morgenthau became more heavily involved in areas of the administration that weren’t explicitly financial. Of Jewish descent, he consistently tried to push Roosevelt to aid in rescuing his people from German persecution. He was also heavily involved in the Lend-Lease agreements between the United States and other countries.

In 1944, Morgenthau branched out into foreign policy, and it was during this time that he came up with his solution for what the post-war world should look like. He explained, “I appreciate the fact that this isn’t my responsibility, but I’m doing this as an American citizen, and I’m going to continue to do so, and I’m going to stick my nose into it until I know it is all right.”

He added, “I want to make Germany so impotent that she cannot forge the tool of war – another world war.”

Morgenthau Plan

The Morgenthau Plan was outlined in a document titled Suggested Post-Surrender Program for Germany.

The plan consisted of three main clauses. First Germany would undergo a mandatory demilitarization, including the disarmament of its citizens and the destruction or removal of all forms of industry that could fuel future militarism. This was to begin immediately after Germany surrendered.

The Ruhr region was a key focus for demilitarization, as it was the core of Germany’s war industry. Under the plan, the Allies would remove all factories and equipment from the area within six months after the war and destroy any that could not be removed. Residents with industrial skills were encouraged to relocate.

Once these two stages were completed, the area would be designated as international territory and managed by the United Nations (UN) to prevent it from becoming a militarized center again.

Partition of Germany

Rather than ask for reparations like with the Treaty of Versailles following the First World War, the Allies would be financially compensated through their control of the region and by taking over the factories and materials once used there.

The management of German territory wouldn’t end there:

- France would get the Saar and territories near the Moselle and Rhine.

- Poland would receive part of East Prussia and southern Silesia.

- Austria would return to its pre-1938 borders.

As for Germany, it would be divided into two separate states. Württemberg, Baden and Bavaria would become South Germany, while Saxony, Thuringia and Prussia would become known as North Germany.

Cordell Hull developed a second plan

At the root of Morgenthau’s plan was his desire to see Germany turned into a country of farmers who, without advanced technology and materials, could never again threaten Europe or the rest of the world with another war.

This wasn’t the only plan created, as Secretary of State Cordell Hull, initially tasked with the job, had also developed his own. While Morgenthau was determined to ruin Germany, Hull wanted to ensure the country could quickly get back on its feet.

Both plans were presented to Roosevelt, who said in a letter to Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands, “There are two schools of thought – those who would be altruistic in regard to the Germans, hoping by loving kindness to make them Christians again, and those who would adopt a much tougher attitude. Most decidedly, I belong to the latter school, for though I am not bloodthirsty, I want the Germans to know that this time at least, they have definitely lost the war.”

The Morgenthau Plan and German propaganda

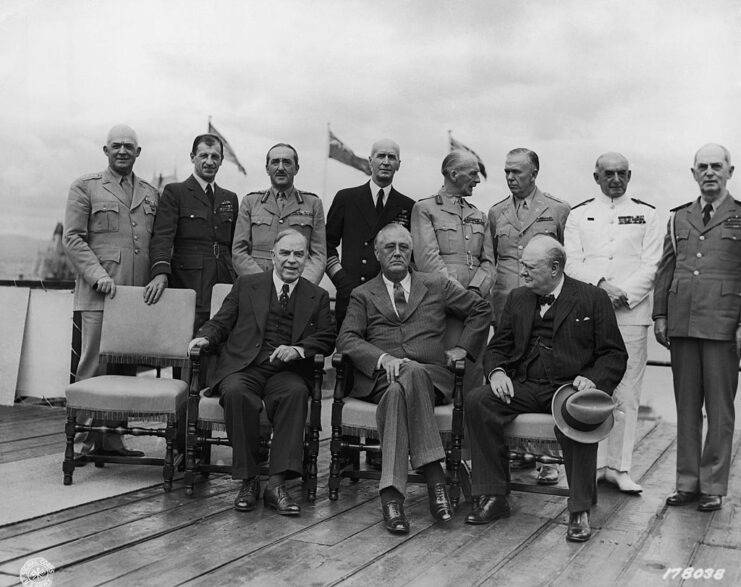

At the Second Quebec Conference in 1944, Roosevelt played a key role in presenting the Morgenthau Plan to international leaders. Initially encountering resistance from Winston Churchill, the plan gained momentum following the US’s offer of a substantial Lend-Lease agreement to the United Kingdom.

After the conference, The New York Times reported on the plan, on September 21, 1944.

Shortly thereafter, Germany’s propaganda ministry used the information to sow discord within the country’s military ranks. Morgenthau’s Jewish background intensified tensions, which were exploited to spread the idea of Jewish conspiracies against the German state. This narrative was then used by the government to justify their heinous treatment of Jewish individuals.

Marshall Plan

When Roosevelt died in April 1945, so, too, did the Morgenthau Plan. For a brief period, it looked like President Harry Truman was going to consider the idea, as he signed Directive 1067 on May 10, 1945, which said America would “take no steps looking towards the economic rehabilitation of Germany [or] designed to maintain or strengthen the German economy.”

This was short-lived, as Turman then signed Directive 1779 that July, designed to provide aid to Germany, instead. That same month, Morgenthau was forced to resign from his position in the Treasury, as he and Truman had too many differences in their political approach. Perhaps this is just as well – calculations show that, if the plan had been implemented, nearly 25 million Germans could have starved.

More from us: These ‘Night Witches’ Weren’t Burned At the Stake – They Bombed German Soldiers

The approach implemented when World War II ended was about as far away from the Morgenthau Plan as possible. Instead of turning the Germans into a bunch of farmers with little-to-no advanced technology, it provided significant economic aid, so they could stabilize their country and recover from the conflict.

The Marshall Plan, as it was called, was highly successful and allowed Germany to rebuild in a way it was never permitted to at the end of the First World War.