In each conflict, certain service members distinguish themselves with their different approaches to fighting. Among them, none was as unconventional as John “Mad Jack” Churchill, a British Commando who fearlessly charged into battle armed not with a rifle or sidearm, but with a humble longbow, a Scottish broadsword, and, notably, a set of bagpipes, which he would skillfully play while rallying his comrades into the fight.

John ‘Mad Jack’ Churchill’s early life

John Malcolm Thorpe Fleming “Mad Jack” Churchill was born in British Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) on September 16, 1906. His father, Alec, was a district engineer in the Ceylon Civil Service, in which his father had previously served.

In 1910, the family relocated to British Hong Kong, where Alec was named the director of public works. While there, the younger Churchill loved to explore the city’s rural areas, leading to a lust for adventure that continued when his family returned to Britain in 1917. Under a decade later, he graduated from the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, and was deployed to Burma with the men of the 2nd Battalion, Manchester Regiment.

While overseas, Churchill and his comrades underwent a signals course in Poona. It was during this time the infantryman became adept at playing the bagpipes, thanks to the assistance of the Pipe Major of the Cameron Highlanders. He was also known to take his motorcycle on what seemed like endless journeys, at one point coming across a herd of hostile water buffalo.

Pursuing a host of unique interests

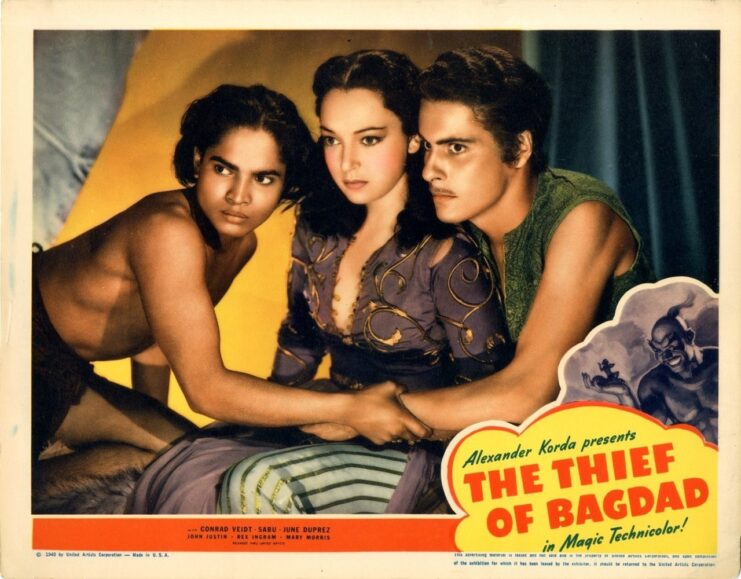

“Mad Jack” Churchill was a man with many passions. After completing his service in Burma and returning to England, he found civilian life in the British Army dull. Consequently, he made the decision to move to Nairobi, Kenya, where he pursued work as both a newspaper editor and a male model, gracing magazine advertisements and making cameo appearances in several films, including The Thief of Baghdad (1924).

Maintaining his enthusiasm for the bagpipes, Churchill dedicated himself to regular practice with the instrument. This dedication eventually led him to participate in a military piping competition in 1938, where he caused quite a stir for beating out the Scottish competitors.

In addition to his prowess with the bagpipes, Churchill was renowned for his skill with a bow and arrow. He proudly represented Great Britain at the World Archery Championships in Oslo, Norway the following year.

Joining the British Expeditionary Force (BEF)

Following the German invasion of Poland in September 1939, “Mad Jack” Churchill, then on the reserve officer list, resumed his commission with the Manchester Regiment, which was sent to France as part of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). Almost immediately, he stood out from the others, opting to wield a Scottish broadsword and a longbow, as opposed to a typical weapon for the time period.

That’s not to say, however, that Churchill wasn’t skilled with a gun. When forced to wield one, he proved to be quite proficient – he just preferred to use his broadsword and longbow.

Shortly after arriving in France, in May 1940, Churchill and his comrades ambushed a patrol of German soldiers near Richebourg, Pas-de-Calais, the veteran raising his broadsword to signal to the others that the fight had begun. He later took part in the Battle of Dunkirk, one of the most devastating engagements of World War II.

John ‘Mad Jack’ Churchill becomes a Commando

Following the Battle of Dunkirk, “Mad Jack” Churchill responded to a request for volunteers to join the British Commandos. Little was known about the unit at this time, but it promised more intense action than he’d experienced up to that point.

By December 1941, at the time of Operation Archery in Vågsøy, Norway, Churchill was second-in-command of No. 3 Commando. Over the course of the one-day mission, he and his comrades took on the German garrison stationed there, with him leading the charge by playing “March of the Cameron Men” on his bagpipes. Once the song was over, he tossed a grenade toward the enemy and charged into battle.

By the end of the raid, the British Commandos had taken 100 enemy prisoners of war (POWs) and destroyed various resources that were vital to the Germans in Norway.

Allied invasions of Sicily and Italy

Over a year after his actions in Norway, “Mad Jack” Churchill took part in the Allied invasions of Sicily and Italy, serving as the commanding officer of No. 2 Commando, with his bagpipes, broadsword and longbow still equipped. In this position, he led his men as they captured the town of Molina, losing his broadsword in the process. Not to worry, however, as he was went back to retrieve it.

Speaking about the successful raid, which resulted in the capture of 42 prisoners of war, Churchill said:

“I always bring my prisoners back with their weapons; it weighs them down. I just took their rifle bolts out and put them in a sack, which one of the prisoners carried. [They] also carried the mortar and all the bombs they could carry and also pulled a farm cart with five wounded in it…

“I maintain that, as long as you tell a German loudly and clearly what to do, if you are senior to him he will cry, ‘Jawohl‘ and get on with it enthusiastically and efficiently whatever the […] situation. That’s why they make such marvelous soldiers.”

Assisting Josip Broz Tito’s forces in Yugoslavia

Following his actions in Italy and Sicily, “Mad Jack” Churchill was sent to Yugoslavia to assist the partisan troops under Josip Broz Tito. In 1944, he led an assault on a position on the island of Brač. The partisans opted to delay the advance upon seeing a gun emplacement, but Churchill and his Commandos moved on, with just he and six others reaching their destination.

Upon their arrival, a mortar shell exploded, killing everyone but him. The last man standing, he put his bagpipes to his mouth and began playing “Will Ye No Come Back Again?” until grenade blasts knocked him unconscious. It’s believed the enemy decided to spare his life because the they believed him to be a relative of British Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

While they didn’t kill him, Churchill was taken as a prisoner of war and sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp, from which he escaped. His freedom, however, was short-lived, as he was recaptured and sent to a camp in Italy. As can be assumed, he also escaped from this facility, with him taking advantage of a power outage and slipping away from the premises.

From there, he walked over 90 miles to Verona, where he came across an American regiment.

What did John ‘Mad Jack’ Churchill get up to after World War II?

Upon returning to his British comrades, “Mad Jack” Churchill was sent to Burma, but, by then, the atomic bombs had already been dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, putting an end to the Second World War.

While many were happy to return home and assume their civilian lives, Churchill wasn’t thrilled about being away from the action. He subsequently qualified as a parachutist and was reassigned to the Seaforth Highlanders. He was then deployed to Mandatory Palestine as an executive officer with the 1st Battalion, Highland Light Infantry.

It was in Palestine that Churchill became involved in protecting a convoy of Jewish nurses and doctors, escorted by Haganah militia, who’d come under attack while delivering medical supplies to Hadassah Hospital in Jerusalem. Some 78 civilians and fighters were killed in the massacre, along with a single British soldier.

Following the attack, Churchill helped evacuate between 500-700 medical professionals, students and patients from the hospital.

An enduring legacy

Following his service in Mandatory Palestine, “Mad Jack” Churchill was an instructor at the land-air warfare school in Australia, where he subsequently developed an interest in surfing. As with his other interests, he quickly mastered the craft, becoming the first person to ride a tidal bore upon his return to England. A few years later, in 1959, he officially retired from the British Army.

More from us: Lessons Learned From the Battle of Tarawa Led to the Creation of the US Navy SEALs

Churchill lived a long and fulfilled life, spending his retirement sailing coal-fired steam launches along the Thames and collecting radio-controlled ship models. On March 8, 1996, in Surrey, he passed away, at the age of 89.