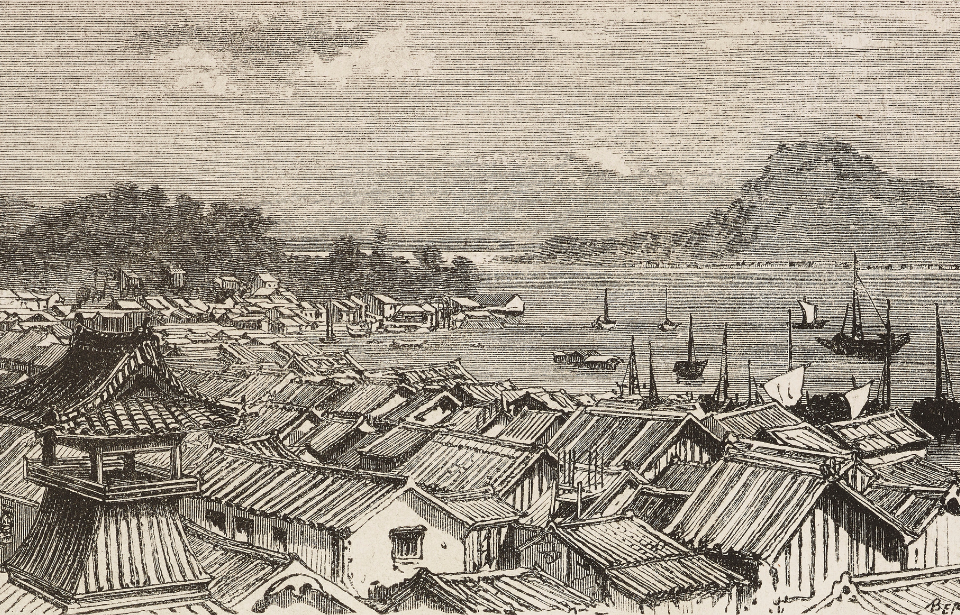

Situated on the northern edge of Japan’s Kyushu island, Kokura was home to one of the nation’s largest military arsenals. It held great importance in America’s strategy to utilize atomic bombs and hasten the conclusion of World War II. Kokura was evaluated as a potential target for both Fat Man and Little Boy. Remarkably, it escaped total destruction on both occasions.

Kokura was the backup for Hiroshima

Hiroshima was designated as the primary target for Operation Centerboard I, due to its housing of two Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) headquarters and its strategic port. Kokura and Nagasaki were secondary targets in the event of complications during the bombing.

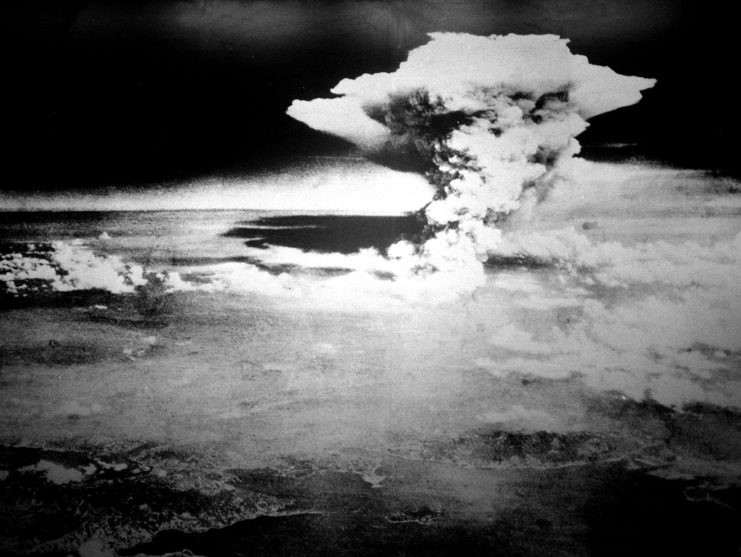

At 8:15 AM on August 6, 1945, Col. Paul Tibbets released the atomic bomb Little Boy over the city from the Boeing B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay. The resulting explosion instantly claimed the lives of an estimated 70,000-80,000 residents.

Had circumstances unfolded differently, Kokura could have been the site of the first atomic bomb drop.

The primary target for Fat Man

The second mission, codenamed Operation Centerboard II, had planned for Kokura to be the primary target for the atomic bomb Fat Man. The US had chosen the city because it was home to one of Japan’s largest military arsenals, which produced chemical and conventional weapons.

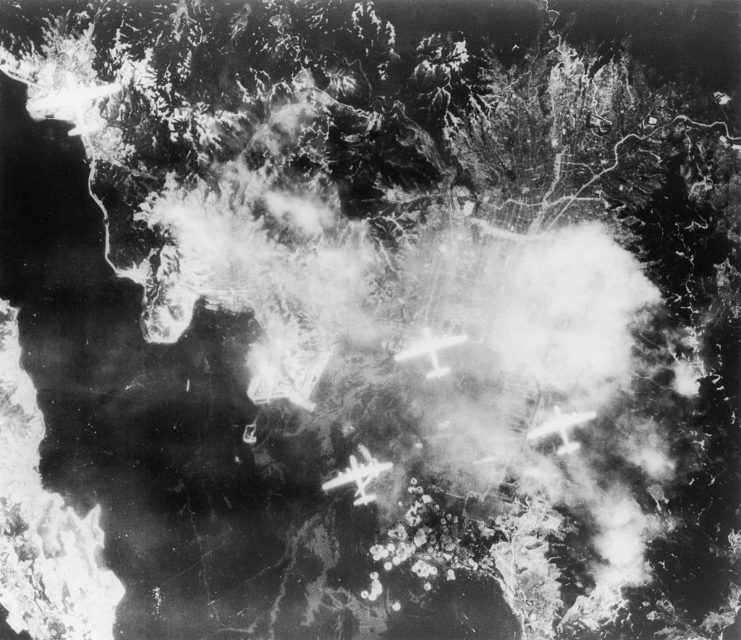

On the morning of August 9, 1945, the Enola Gay flew alongside the B-29 Laggin’ Dragon to scope out the weather conditions for the bombing later that day. They reported a 3/10 cloud coverage, with a forecast of improving conditions. This turned out to not be the case.

Unfavorable (or favorable) cloud coverage

The report from the weather aircraft was promising enough that Kokura was confirmed as the primary target. However, by the time Maj. Charles Sweeney, pilot of the B-29 Bockscar, made it over Kokura, the conditions had drastically changed. Instead of the 3/10 coverage, Sweeney reported 7/10 thick cloud cover.

One of the stipulations in dropping the atomic bomb was that the target needed to be seen visually, as the US didn’t trust radar-assisted bombing for such a dangerous weapon. Sweeney’s early report said that the “bomb must be dropped visually, but I don’t think our chances are very good.” After making three runs over the city, hoping for a break in the cloud cover, he reported that “at no time was the aiming point seen.”

Kokura and its residents were spared from the devastation of the atomic bomb.

Dropping the atomic bomb on Nagasaki

It was the lack of visibility, as well as depleting engine fuel, that forced Sweeney to change his course to the secondary target: Nagasaki. Even still, cloud cover was still causing issues.

A break in the clouds allowed Sweeney to gain visibility of the target and he successfully dropped Fat Man on Nagasaki at 11:02 AM. It exploded in the sky somewhere between the Mitsubishi Nagasaki Arms Factory’s Ohashi and Mori-Machi plants. The location was actually off target, as the pilot had dropped the bomb two miles from the planned hypocenter. That didn’t reduce the number of casualties, however, as tens of thousands of residents and factory workers lost their lives.

A firebombing/steel plant smoke screen

The weather obviously had a major impact on the decision to abandon Kokura and head to Nagasaki, but there may have been other influences, as well. For one thing, the neighboring city of Yahata was the target of US incendiary bombs the day prior. Dubbed the “Pittsburgh of Japan,” it was one of the country’s largest steel manufacturers, and it was believed the firebombing would provide smoke coverage over Kokura.

Additionally, in 2014, an 85-year-old former steel worker in Yahata, Satoru Miyashiro, explained that the city was terrified it would receive a devastating blow, so the plant burned coal tar to produce a thick black smoke that would prevent American bombers from dropping anything.

It’s difficult to say whether any one of these variables acted independently to create enough cloud cover to divert the attack to Nagasaki or if it was a combination of all three. Either way, Kokura was saved that day from being the victim of one of the most destructive weapons in the world.

Kokura in the 21st century

Kokura and Yahata were absorbed by the city of Kitakyushu in 1963, and have become a memorial for the near-bombing of the former. Kitakyushu Park is home to the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Memorial Bell and Monument, and the Kitakyushu City Museum of Peace opened in April 2022.

More from us: One of Germany’s Top Test Pilots During World War II Was a Woman

After the bombing of Nagasaki, the phrases “Kokura’s Luck” and the “Luck of Kokura” became a popular Japanese saying for when one avoids danger without even being aware something bad was going to happen.