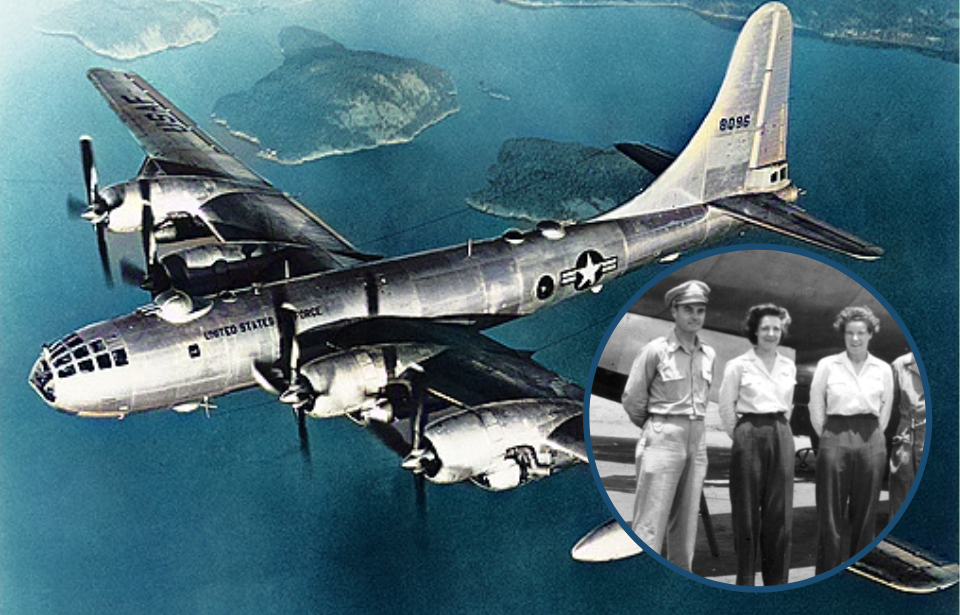

As the events leading up to the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki unfolded, Paul Tibbets faced the task of instructing a group of pilots in the operation of the newly-manufactured Boeing B-29 Superfortress. However, he encountered a significant challenge: the aviators staunchly resisted boarding the aircraft. This resistance stemmed from the B-29’s substantial size and comparatively limited testing, in comparison to other aircraft deployed during World War II.

The pilots were apprehensive about the perceived risks associated with flying this unfamiliar bomber. Nonetheless, their refusal to utilize the B-29s wasn’t a viable option. In response, Tibbets devised a clever strategy – he trained two female pilots to conduct flight demonstrations for the male aviators. This innovative plan achieved resounding success.

Problems with the B-29’s engines

After Paul Tibbets had served in both the European and Pacific Theaters, he received orders to return to the US in 1943 to help with the development of the B-29 Superfortress. Following the completion of the bomber’s testing phase, he assumed the role of director of operations for the 17th Bombardment Operational Training Wing (Very Heavy). His primary responsibility was to train pilots in the operation of the new aircraft.

However, the task of instructing these aviators proved to be a formidable one. They had genuine reasons for their reluctance, given the B-29’s history of unreliable engines and frequent fires, as well as its relative lack of comprehensive testing compared to other aircraft. Furthermore, the bomber’s notably larger size posed a considerable departure from those previously flown by the US Army Air Forces.

The women who flew the B-29 Superfortress

Tibbets thought that if he could get female pilots to train on the aircraft, the men might not be scared to fly the B-29. He recruited two Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs) for the role. He didn’t disclose to Dora Dougherty Strother or Dorothea Johnson “Didi” Moorman that there had been issues with the aircraft, and the pair didn’t experience any problems when piloting them.

Neither woman had even flown a four-engine aircraft, which is why they were picked for the job – Tibbets wanted to show that anyone could fly a B-29. He trained Strother and Moorman for only three days before deciding they were ready to give demonstrations to the male pilots.

The pair flew various flights out of the base in Alamogordo, New Mexico, with different aircrews onboard each time.

Reception as demonstration pilots

Strother and Moorman were successful in getting the male pilots to fly the B-29s. A maintenance bulletin written by Maj. Harry Shilling gave them praise for both their flying abilities and knowledge of the aircraft. He encouraged the men on the base to ask them questions about how to handle the bombers and emulate their impressive takeoffs.

Despite their success, Strother and Moorman didn’t have their jobs as demonstration pilots for long. When Tibbets’ superiors found out he was letting women fly the B-29s, they forced him to shut down the program. Air Staff Maj. Gen. Barney Giles told him that the women were “putting the big football players to shame.”

Remembering their role

Although their role as demonstration pilots may seem small, it wasn’t viewed as such by the men who watched them. On August 2, 1995, Harry McKeown, a retired lieutenant colonel with the US Air Force, wrote a letter to Strother about her role flying the B-29s. He’d met her and Moorman in 1944 when they brought a B-29 to Clovis Army Airfield, where he served as the Director of Maintenance & Supply and a test pilot.

He said that after their demonstration “we never had a pilot who didn’t want to fly the B-29,” and ended his letter on a more personal note. “I still want to thank you for your helping me that day at Clovis,” he wrote. “I will admit that I was scared… You made the difference in my flying from then on. I wasn’t the only pilot that felt this way, and I am sure that they would thank you too if they knew where you were.”

Life after the war

Both women carried on with the WASPs until the organization disbanded in 1944. Strother went on to earn her PhD from New York University and worked for Bell Helicopters from 1962-86. She kept in touch with McKeown and married him in 2002. Moorman raised five children in North Carolina after the war, and kept in close contact with Tibbets until her death in 2005.

More from us: Lumber Jills: The Women Who Made Up Britain’s Timber Corps

The WASPs, including Strother and Moorman, were denied military veteran status until 1977, when the US House and Senate voted to grant them what they had earned. This decision made them eligible for veterans benefits and also allowed the woman to commemorate their fallen sisters as veterans – something they hadn’t previously been able to do.