Throughout the Second World War, opposing forces captured a significant number of prisoners of war (POWs), totaling hundreds of thousands. Despite the meticulous care standards outlined by the Geneva Convention, the camps in Allied-occupied Germany purposefully established a classification system to evade these responsibilities.

Known as the Rheinwiesenlager and formally designated as “Prisoner of War Temporary Enclosures” (PWTE), these facilities are infrequently acknowledged or discussed.

Allied success in Europe following the D-Day landings

Following the resounding success of the D-Day landings, the Allies swiftly pushed through occupied territories, into Germany. As some enemy soldiers continued to resist, a considerable number chose to surrender, placing the responsibility for their well-being squarely on the shoulders of the Allied forces.

Initially, these surrendered troops were divided between the British and Americans. However, in early 1945, the British declined to accept more individuals into their existing camps. Consequently, the Americans shouldered the weighty burden, a formidable challenge given the increasing number of German POWs as the Allies penetrated deeper into the heart of Germany.

In response to this escalating demand, the US Army devised a solution: the establishment of the Rheinwiesenlager, a network of camps scattered throughout Allied-occupied Germany. Although initially set up in April 1945, their significance grew even more following Germany’s surrender, as they served as a means to preempt a potential uprising against the Allies.

Layout of the Rheinwiesenlager

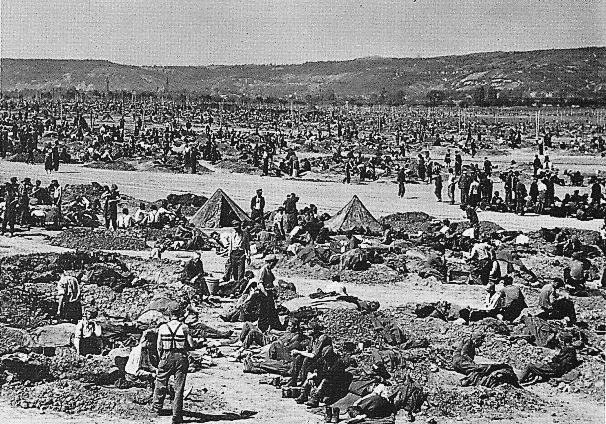

The Rheinwiesenlager were established on Allied-controlled land in West Germany, developed on farmland near railways by enclosing designated spaces with barbed wire. The land plots were subsequently divided into smaller camps, each intended to hold 5,000-10,000 people. However, many exceeded their intended capacity, with occupancy levels often surpassing 100,000 prisoners. Estimates suggest an overall total of between one and 1.9 million individuals.

The detainees at the Rheinwiesenlager were typically ordinary members of the Wehrmacht, as German officers, SS members, and others of interest were taken to different locations.

The internal organization of the camps was largely delegated to the prisoners themselves, forcing them to manage work, medical care and cooking. The guards overseeing the enclosures were, for the most part, also prisoners, enticed with more resources than their peers to ensure compliance within the barbed wire confines.

Within the compounds, buildings were primarily used as kitchens, medical facilities and for administrative purposes. Notably, they weren’t used for housing prisoners; instead, most detainees were compelled to dig holes in the ground for accommodation.

Disarmed Enemy Forces (DEFs)

If sleeping in outdoor holes wasn’t indication enough, these prisoners were treated very poorly by their captors. Much of this was facilitated by their categorization – not as POWs, but as Disarmed Enemy Forces (DEFs).

Before the Rheinwiesenlager opened, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower established the new classification, as it meant DEFs wouldn’t have the same rights granted to POWs under the Geneva Convention on Prisoners of War (1929), as they were members of state that no longer existed. This allowed many things to happen.

It meant the Americans could “legally” prevent the Red Cross from visiting and stop the organization from sending supplies. The Geneva Convention was designed to prevent the poor treatment of POWs. Without such protections, the DEFs were mistreated with little to no consequences suffered by their captors.

All this has led many to now view the inhumane actions of Eisenhower and those operating the Rheinwiesenlager as purposeful.

Rheinwiesenlager conditions

In general, the conditions in the Rheinwiesenlager were appalling.

Historian Stephen Ambrose investigated claims made about the camps and concluded, “Men were beaten, denied water, forced to live in open camps without shelter, given inadequate food rations and inadequate medical care. Their mail was withheld. In some cases prisoners made a ‘soup’ of water and grass in order to deal with their hunger.”

Pleading for more food wasn’t a viable option either, as those prisoners were often shot under the pretext of being “escapees” if they approached the barbed wire fences. There were also reports indicating locals attempting to provide aid to the POWs would be shot.

Legacy of the Rheinwiesenlager

Given the living conditions of the Disarmed Enemy Forces, it’s no wonder the death toll was high. However, because they weren’t officially known as prisoners of war, few records were kept. Instead, many Germans would simply go missing from roll call, never to be seen again.

Due to the lack of records, death estimates vary, depending on who you ask. The official statistics from the US Army state that around 3,000 people died while in the Rheinwiesenlager. German estimates, however, provide a figure of 4,537.

James Bacque, the author of Other Losses: An Investigation Into the Mass Deaths of German Prisoners at the Hands of the French and Americans After World War II, alleges the number is between 100,000 and one million. However, his claims have been discredited by his peers.

More from us: The Battle of Cologne Saw a Legendary Standoff Between a Panther and a Pershing

Want War History Online‘s content sent directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter here!

Regardless of the overall death toll, the treatment of DEFs has been heavily criticized, despite it going largely unnoticed in more recent years. Many have pointed out that the Americans violated a host of international laws on the treatment of prisoners, even though they weren’t classified as POWs, particularly in their feeding – or lack thereof.