After years of speculation and careful planning, the US military undertook the development of an anti-ballistic missile (ABM) aimed at intercepting Soviet re-entry vehicles (RVs). Known as the “Sprint missile,” this weapon was incorporated into the US Army between 1975-76, showcasing an extraordinary capability to reach remarkable speeds within seconds.

Unfortunately, the effectiveness of the ABM system was short-lived, as policy shifts eventually led to its discontinuation.

Last-ditch defensive strategy

As early as the 1940s, the US military began efforts to develop a weapon capable of intercepting theater ballistic missiles (TBMs). In 1955, the Army awarded a contract to Bell Telephone Laboratories to tackle this challenge. The company’s assessment concluded that creating an anti-ballistic missile specifically tailored to thwart TBMs was technologically feasible, requiring only minor modifications to the Nike Hercules surface-to-air missile (SAM).

The development of the Nike Zeus commenced in 1955, under Bell’s guidance. This endeavor involved numerous enhancements, including robust radar systems designed to detect intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) well in advance, facilitating effective countermeasures. Moreover, it integrated faster and more advanced computer technology.

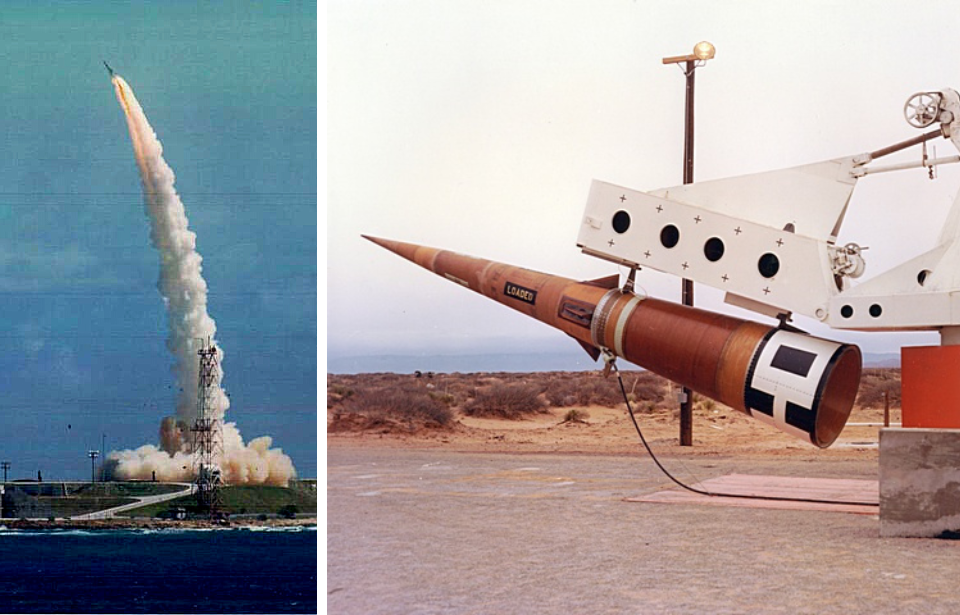

Extensive testing of the Nike Zeus occurred in 1959 and, three years later, a base was established on Kwajalein Island. The anti-ballistic missile demonstrated its effectiveness by intercepting test missiles and accurately targeting low-flying satellites.

Issues with the Nike Zeus

During development of the Nike Zeus, it became clear the ABM had quite a few issues that made it easy to defeat.

As it used 1950s-era mechanical radar, the number of targets it could track were limited. A report at the time even suggested that four warheads had a 90 percent chance of destroying a Nike Zeus base. This initially didn’t seem like a big issue, but, as ICBMs became less expensive to produce, the threat of the Soviet Union using them against the United States became more probable.

Over time, even more problems presented themselves. After nuclear testing in space in 1958, it was found radiation from warhead detonations would blanket large areas, blocking radar signals above an altitude of 60 km. If the Soviets caused an explosion above a Nike Zeus site, they could prevent observation until it too late to launch a counterattack.

Additionally, they could use radar reflectors on their warheads, which created multiple false targets.

Replacing the Nike Zeus with the Nike-X

At the behest of then-Secretary of Defense Neil H. McElroy, the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) was tasked with investigating pertinent issues. Their findings revealed that both high-altitude nuclear explosions and radar decoys ceased to be effective in the lower atmosphere due to thickening. To address this challenge, the recommendation was to await the warhead’s descent below 60 km, at which point radar detection could resume.

However, a new obstacle emerged. The warheads, hurtling at speeds of Mach 24, necessitated the deployment of similarly high-speed missiles to intercept them before reaching their targets.

Subsequently, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, who succeeded McElroy, proposed to President John F. Kennedy that funds allocated to the Nike Zeus be redirected toward developing the ARPA’s system. His argument swayed JFK and paved the way for the creation of the Nike-X.

Introducing the Sprint missile

The Sprint missile took center stage in the Nike-X program. Armed with a W66 thermonuclear warhead, its mission was to intercept re-entry vehicles (RVs) at a distance of 60 km.

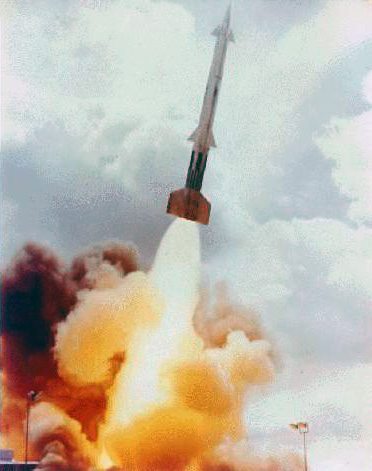

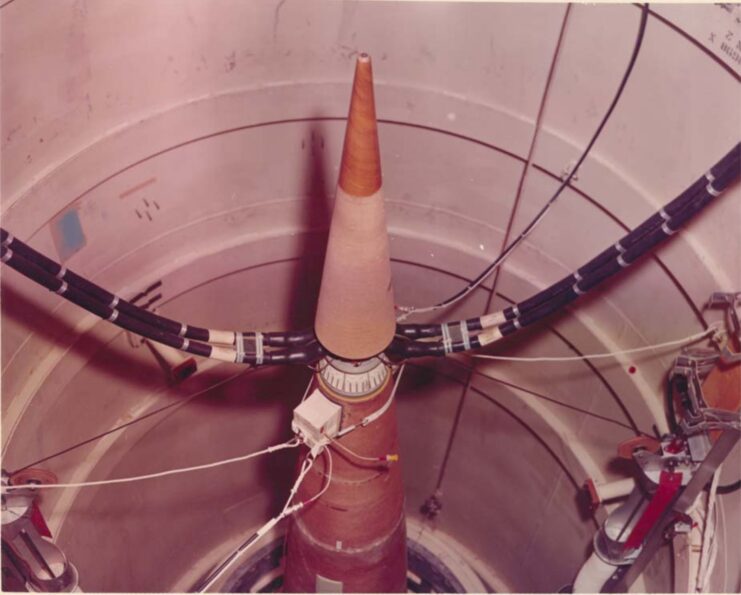

Measuring 27 feet in length and weighing 7,500 pounds, the Sprint relied on a precise launch sequence. Initially housed in a silo, the missile was launched when its cover was blown off by an explosive-driven piston. Once airborne, it would adjust its trajectory toward the target, guided by ground-based radio command guidance. This tracked incoming RVs via phased array radar and led the missile to its destination, where it annihilated its target through neutron flux.

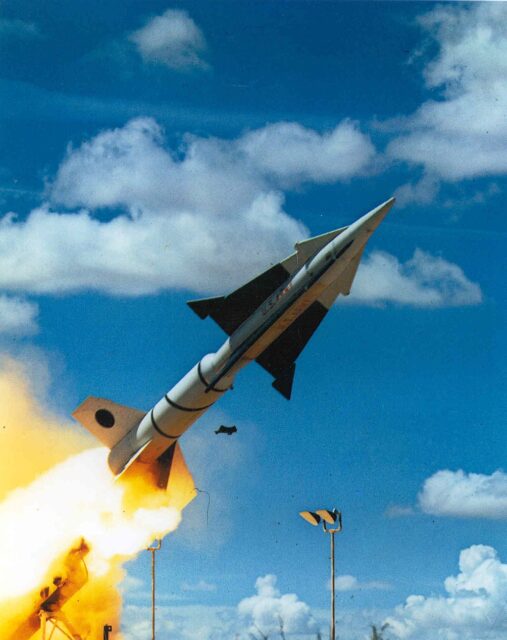

The Sprint’s performance was nothing short of remarkable. Engineered to accelerate at a staggering 100 g and reach Mach 10 in a mere five seconds, it operated at low altitudes where its skin temperature soared to 6,200 degrees Fahrenheit. To counter this, an ablative shield was employed, creating a distinct white glow around the missile as it traversed the sky.

Navigating through such extreme conditions necessitated powerful radio signals capable of penetrating the plasma enveloping the missile, ensuring precise guidance toward its intended target.

HIBEX missile

The High Boost Experiment (HIBEX) missile is considered a kind of predecessor to the Sprint missile, as well as its competitor. It was another high-acceleration missile designed in the early 1960s, and it actually provided a technological transfer to the Sprint development program.

Unlike the Sprint missile, the HIBEX had a high initial acceleration rate of nearly 400 g. Its role was to intercept RVs at an even lower altitude – as low as 20,000 feet. Unlike the Sprint, it featured a star-grain “composite modified double-base propellant” that was created by combining zirconium staples with aluminium, double-base smokeless powder and ammonium perchlorate.

Sprint II missile and the end of the Nike-X program

Over time, the Nike-X evolved into the Safeguard Program, prompting the Los Alamos National Laboratory to explore alternative warheads for a fresh design. Subsequently, efforts were directed toward enhancing the Sprint II missile.

By 1971, the Sprint II became an integral part of the Safeguard Program, serving as a protective measure for Minuteman missile fields. Its interceptor boasted a slightly reduced launch dispersion, compared to its predecessor, which enhanced hardness and minimized miss distance for improved accuracy.

Despite ongoing optimization efforts by Los Alamos to refine the design, the operational lifespan of both missiles was relatively brief.

Want War History Online‘s content sent directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter here!

During the 1970s, shifts in the ABM policies of both the US and the Soviet Union raised doubts about the effectiveness of the Safeguard Program. It was deemed unnecessary and expensive, leading to its cancellation. The official discontinuation date is unclear, but reports persisted until 1977.