Most enthusiasts of military history and cinema are familiar with the iconic 1963 film, The Great Escape. With a cast including Steve McQueen, James Garner, Charles Bronson and Richard Attenborough, it boasts a lineup of Vintage Hollywood icons. Yet, the true story that served as the inspiration for the film is not well known.

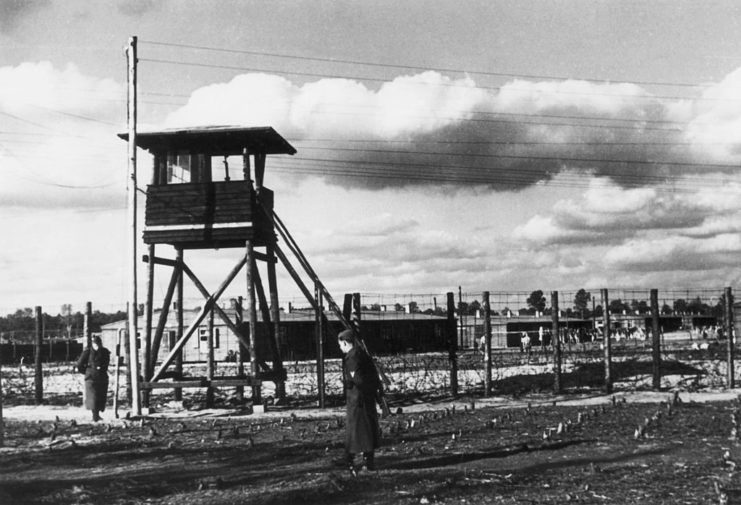

Stalag Luft III

The Great Escape was based on Paul Brickhill’s 1950 non-fiction book of the same name. The veteran had served as an Australian fighter pilot, flying Supermarine Spitfires as part of the Desert Air Force in North Africa. While flying over Tunisia in March 1943, he was shot down and taken as a prisoner of war (POW) to Dulag Luft, after which he was sent to Stalag Luft III.

Stalag Luft III was located in Lower Silesia, near the town Sagan (now Żagań, in modern-day Poland). The camp was around 100 miles southeast of Berlin. This specific location was chosen to house a German POW camp because it was a difficult area to escape from, especially by tunneling. In fact, the Germans took elaborate measures to prevent any such attempts, including raising the prisoners’ huts and burying microphones nine feet underground along the perimeter fencing.

Stalag Luft III was built on top of yellow sand, which was tough to tunnel through. This also meant the structural integrity of any tunnel would be weak.

Tunnels were worked on for nearly a year

In the Spring of 1943, over 600 prisoners at Stalag Luft III began digging tunnels, led by Royal Air Force (RAF) pilot Roger Bushell, who’d been shot down over France while assisting with the evacuation of Dunkirk. The squadron leader hoped to get 200 men out in a single attempt by digging three separate tunnels. He figured that, if a German discovered one, they wouldn’t imagine two more were also being built, and the escape plan could progress.

These three tunnels – nicknamed “Tom,” “Dick” and “Harry” – ran deep, about 30 feet below the surface. They were held up with pieces of wood, with 4,000 bed boards used in their construction. Other materials, including tin cans, were used to reinforce the tunnels.

The prisoners used stolen wire to hook up to the camp’s electrical supply, and strung lightbulbs in the tunnels to illuminate the dark space. To ensure the German guards didn’t learn what was going on, they developed an elaborate lookout system and used subtle signs to signal to others that a guard was approaching.

They also bribed the guards with numerous Red Cross goods that were unavailable in Germany, including chocolate, coffee, soap and sugar. In return, the prisoners received cameras and travel documents that they turned into identity cards, passports and travel passes.

Failing to escape from Stalag Luft III

In March 1944, the final tunnel, Harry, was completed. Prior to this, the Germans had discovered Tom and destroyed the tunnel. The prisoners had also decided to turn the other into a storage space, meaning that, when Harry was completed, it was the only usable tunnel for escape.

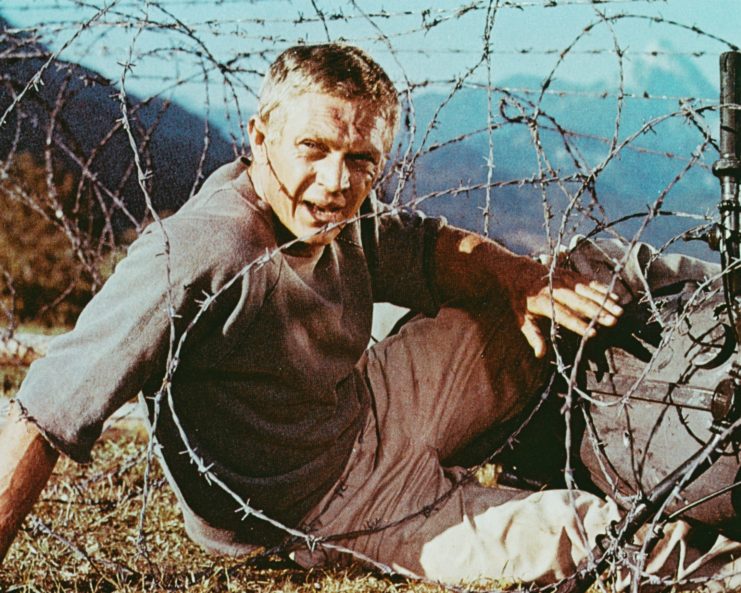

The escape was set to occur on March 24, 1944. However, the prisoners discovered a problem as the first escapee left the tunnel. When digging Harry, they’d assumed the tunnel would reach a nearby forest. However, it was soon apparent it wasn’t quite long enough, as it exited just short of the tree line, close to a watchtower.

Because of the snow on the ground and the tunnel not ending in the forest, the prisoners realized that any escapee would leave a trail as they walked into the forest. To avoid being caught, they reduced the number of escapees from one every minute to 10 an hour. Then, at around 1:00 AM, a portion of the tunnel collapsed and had to be quickly repaired.

Despite these unexpected issues, a total of 76 prisoners were able to crawl through the tunnel to freedom. Unfortunately, at around 5:00 AM on March 25, a German soldier on patrol nearly felling into the tunnel’s exit, exposing the escape plan.

Recapturing the escapees

Following the discovery of the tunnel, German authorities launched an large search effort for the escaped prisoners, ramping up patrols, scouring nearby farms and hotels, and setting up roadblocks. Within two weeks, they had successfully recaptured 73 out of the 76 men who had fled.

In response to the breakout, the German Führer personally sanctioned the execution of 50 of the escapees as a deterrent to others incarcerated at Stalag Luft III. Although depicted differently in The Great Escape, the Gestapo carried out these executions individually or in pairs, in remote locations.

Subsequently, in 1947, a military tribunal convicted 18 German soldiers of war crimes related to these killings.

The Great Escape (1963)

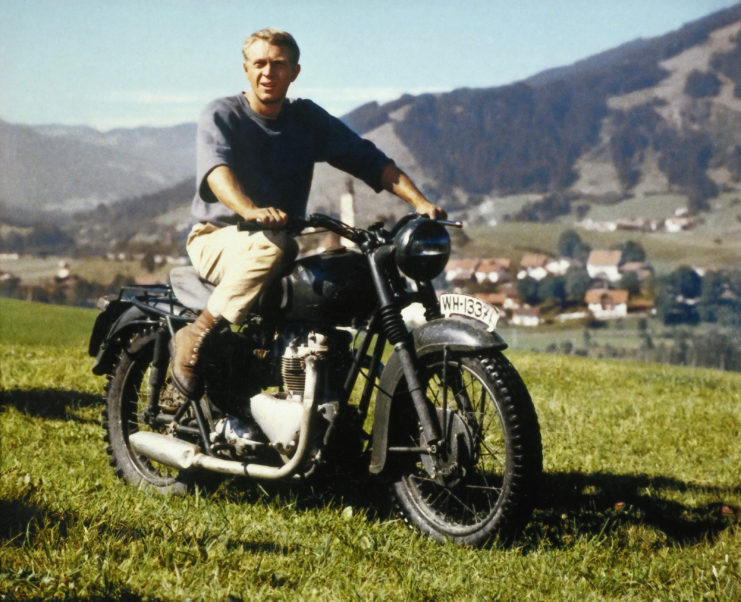

In 1963, a heavily fictionalized retelling of the events at Stalag Luft III was released. Titled The Great Escape, it featured a star-studded cast as its main characters. Among the aspects of the story that were changed to better fit American audiences was the role of the US personnel imprisoned at the POW camp. Despite being moved seven months prior to the escape attempt, they are depicted in the film as having a much larger role, thus erasing the impact of the Canadian soldiers held there.

Despite the historical inaccuracies, The Great Escape received a positive reception, becoming one of the highest-grossing films of 1963. It received a number of award nominations, including the Oscar for Film Editing and the Golden Globe for Best Picture, and was named one of the Top 10 Films of the Year by the National Board of Review (NBR) of Motion Pictures.

More from us: Solo Snipers and Infinite Ammo: 10 Errors Movies Make Involving Guns

The Great Escape has left a lasting legacy not only on Hollywood, but in regards to the stories of those who fought during the Second World War. Many credit the film with keeping alive the memories of the 50 prisoners who were executed following the escape attempt, ensuring their sacrifice isn’t forgotten to time.