During the Cold War, the US Army worked on a covert operation called Project Iceworm. The goal was to construct a hidden military base beneath Greenland’s ice sheet, equipped with numerous nuclear missiles and launch sites. Unfortunately, progress was halted by the unpredictable and unstable ice conditions, leading to the project’s eventual cancellation.

Nevertheless, a smaller military facility was finished before the project was officially terminated.

Getting permission from Denmark

In 1951, the United States and Denmark signed the Defense of Greenland agreement, which allowed NATO members to explore the establishment of military installations in Greenland to safeguard the nation and allied treaty areas. Essentially, this agreement gave the US the right to set up a base in Greenland.

The agreement did not extend to the placement of nuclear missiles. When the US Army began planning a base in Greenland, Danish Prime Minister H.C. Hansen advised against introducing nuclear missiles to avoid escalating international tensions. Nonetheless, when US Ambassador Val Petersen inquired about the base, Hansen did not explicitly oppose the idea, allowing the project to proceed.

The Pentagon portrayed the initiative as a trial to assess construction techniques in Arctic conditions, address potential challenges with portable nuclear reactors, and conduct scientific studies on Greenland’s ice cap. However, officials left out a crucial fact: the real aim of the military base was to station nuclear missiles in Greenland.

Camp Century

The Army named the project “Camp Century,” a name that provided a highly-publicized front for the real mission. Construction kicked off in June 1959 and wrapped up a little over a year later, in October 1960.

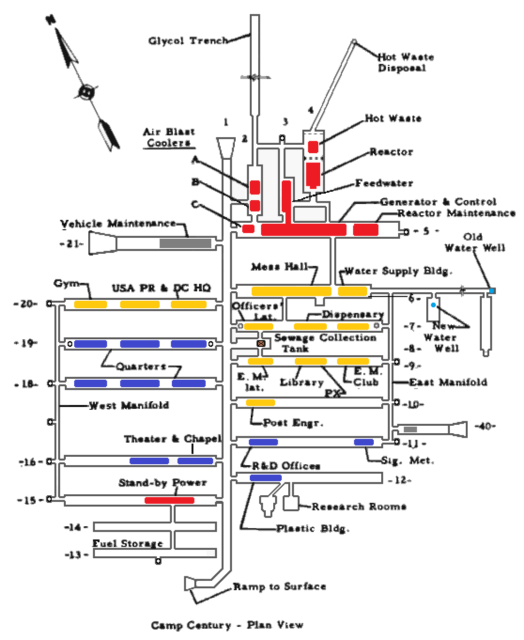

The task was a challenging one. First, a three-mile-long road had to be built, essential for transporting equipment and supplies to the site where the facility would be built. Trenches were then carved into the ice, topped with steel arches to form the roof, and buried under snow for added protection and concealment. The longest of these trenches, called “Main Street,” stretched over 1,000 feet.

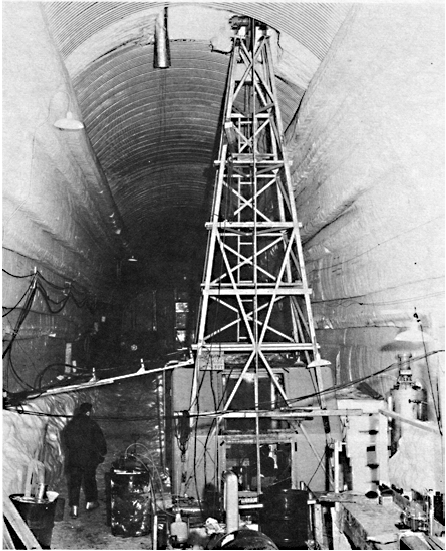

Within the trenches, wooden structures were built, with gaps between the walls and the ice to minimize melting caused by internal heat. The base was well-insulated, tapped the ice for fresh water, and was powered by the world’s first portable nuclear reactor, the PM-2A, installed in 1960.

In total, Camp Century could house more than 200 soldiers and boasted a kitchen, cafeteria, laundry, communications center, hospital, chapel, and even a barbershop. It had 26 tunnels, and its construction was a critical test of the possibility of operating beneath the ice.

Project Iceworm

Camp Century hid the Army’s actual goal, Project Iceworm, which sought to expand the tunneling model of Camp Century by creating an additional 52,000 square miles of tunnels—an area over three times larger than Denmark.

This vast military complex was intended to house 600 “Iceman” ballistic missiles that the US Military planned to deploy at intervals of four miles, along with the creation of 60 Launch Control Centers. By placing these missiles underground in Greenland, the US could quickly deploy them against enemy nations. During the Cold War, the US government’s primary focus was the Soviet Union, and locating these missiles in Greenland allowed for strategic targeting across much of the USSR.

The Iceman missile, based on the Minuteman Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM), had a range of 3,300 miles. Ensuring the operational readiness and deployment of these missiles required a stationed force of 11,000 soldiers at the base.

Problems with Project Iceworm

On the surface, Project Iceworm seemed like the perfect plan; nuclear missiles deployed within range of Soviet targets was ideal for the US. However, problems soon came to light.

After just three years, ice core samples showed that Greenland’s ice cap was moving faster than originally anticipated. Already, in 1962, the reactor room’s ceiling had begun to drop, requiring it be lifted five feet. At the rate the ice was moving, the base and its tunnels would be destroyed in as little as two years.

With this information, the Army realized it simply couldn’t risk storing hundreds of nuclear missiles there. Additionally, the modifications required to create the Iceman missiles would be costly, and issues with communicating with the weapons while operating under several feet of Arctic snow proved to be detractors from further pursuing Project Iceworm.

The operation was officially canceled in 1963, and no missiles were ever deployed to Greenland. In the summer of that year, Camp Century was converted into a summertime military base, and its PM-2A nuclear reactor was shut down, with the facility running on diesel power. The reactor was removed the following summer, and Camp Century was ultimately abandoned in 1966.

Campy Century could have a long-lasting ecological impact

Project Iceworm remained a secret until the Danish Institute of International Affairs began investigating the former military base. Documents about the Army’s true intentions were declassified in 1996, and the secret about Camp Century was finally revealed to the public.

Years after the base was shuttered, its tunnels collapsed, and now a thick layer of ice covers the once-operational facility, making it virtually unreachable. However, the operation wasn’t for nothing, as Camp Century actually provided valuable information via the collection of some of the world’s first ice core samples.

New! Want to become a trivia master? Sign up for our War History Fact of the Day newsletter!

The environmental effects of Project Iceworm may be awaiting society in the future. While Camp Century was in operation, its nuclear reactor produced over 47,000 gallons of radioactive waste that’s still buried under Greenland’s ice cap.

Scientists believe that, if climate change continues at the rate it currently is, the ice cap could melt enough to expose the nuclear waste by 2100, which could negatively impact the ecosystems within the surrounding area.