Alongside the Allies who faced the challenges in the Territory of Papua were a band of heroic figures known as the “Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels.” These Indigenous individuals offered invaluable aid to wounded Australian soldiers grappling with the unforgiving and unfamiliar landscape. Venturing through dense jungles, perilous mountains and harsh conditions, they delivered aid and solace.

Kokoda Track Campaign

The Kokoda Track Campaign was a notoriously grueling engagement in the Pacific Theater that was fought by the Australian and Japanese from July to November 1942. Spanning between 37 and 60 miles, depending on the route, the stretch of path witnessed the fight for control over what was then Australian-controlled Papua.

With the combatants forced to navigate rugged and unforgiving terrain, the campaign was marked by intense fighting, harsh environmental conditions and a relentless struggle for control. The Australians, outnumbered and ill-equipped, displayed immense courage and resilience as they defended against the advancing Japanese.

Key engagements included the fighting at Isurava, Brigade Hill and Imita Ridge, with both sides experiencing heavy casualties. Australia suffered 625 dead and 1,055 wounded, while the Japanese are estimated to have lost 2,050 soldiers and an additional 4,500 injured.

Ultimately, the Australians, supported by the Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels, successfully repelled the Japanese advance and secured a crucial victory.

‘Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels’

While the name might seem peculiar, the Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels earned their moniker from British soldiers in the 19th century, due to their distinctive hair. These individuals were local villagers who served under Australian troops during the Second World War.

Under the command of Maj. Gen. Basil Morris, these men could be conscripted as military carriers for three-year terms. Some would volunteer willingly, especially if offered a shorter service duration, while others were compelled into service.

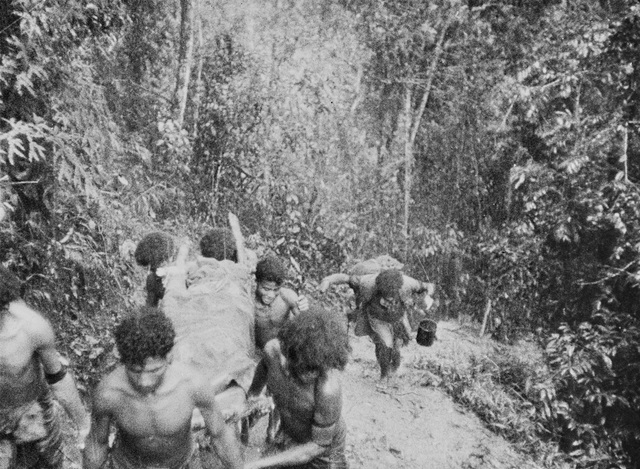

The primary role of the Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels was to transport supplies and ammunition for troops, and they played a significant role in aiding the wounded as they journeyed to field hospitals. Typically, they would gather materials from air drop zones and transport them for the Australians. On their return journey, they would carry any wounded soldiers with them.

Poor treatment on the frontlines

Soon after fighting broke out along the Kokoda Track, various Australians wrote home about the Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels. Sapper Bert Beros wrote a poem called The Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels, which was published in newspapers back in Australia.

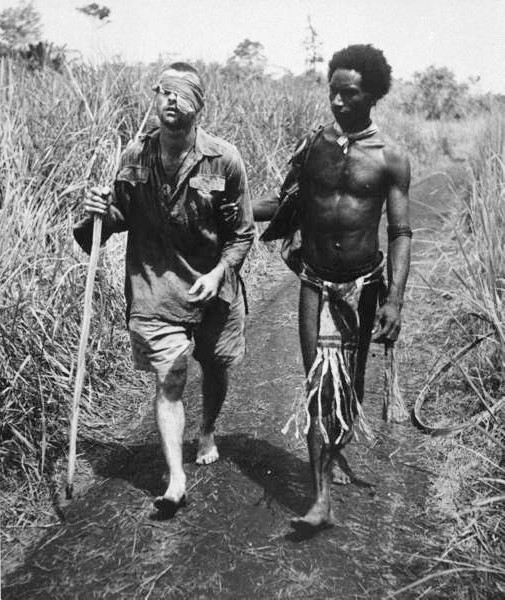

This idea of the Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels was only furthered in other letters home, proclaiming these men to be devoted and dedicated to the cause. Photojournalist George Silk captured the incredible photo of Raphael Oimbari helping recently-blinded Pvt. George Whittington to a field hospital, an image that tugged on everyone’s heartstrings and helped solidify the myth of these Indigenous men.

Although they’ve become somewhat mythologized for their role in the war effort, it cannot be overstated that much of this was forced labor in horrific conditions. While they certainly saved the lives of many Australians, the well-being of these men wasn’t prioritized, perhaps making their own frontline efforts even more admirable.

Dr. Geoffrey Vernon wrote about what they experienced: “The condition of our carriers at Eora Creek caused me more concern than that of the wounded. Overwork, overloading… exposure, cold and under-feeding were the common lot…”

Guardian angels

Even through the worst of these conditions, there’s a reason these war carriers were viewed as angels by the Australians. Regardless of their motives for doing so, the Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels put a lot of work into caring for the wounded. Maj. Henry Steward said the men they carried were “tended with the devotion of a mother and the care of a nurse.”

This level of dedication and care wasn’t abnormal, either. Maj. Gen. Frank Kingsley Norris said, ” They carried stretchers over seemingly impassible barriers, with the patient reasonably comfortable. The care they give to the patient is magnificent.

“If night finds the stretcher still on the track, they will find a level spot and build a shelter over the patient. They will make him as comfortable as possible, fetch him water and feed him if food is available, regardless of their own needs. They sleep four each side of the stretcher and if the patient moves or requires any attention during the night, this is given instantly. These were the deeds of the Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels – for us!”

Legacy of the ‘Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels’

By all accounts, the Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels didn’t abandon a single living injured patient, even under fire. It’s generally accepted among historians that the number of 625 dead during the Kokoda Track Campaign would’ve been significantly higher without their service.

How was this group of forced conscripts treated after the war? As early as 1943, some Australian soldiers wanted them to receive financial compensation and recognition for their acts. Nothing ever came of this, and it wasn’t until the 2000s that the Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels received governmental recognition.

In a 2008 speech, Sen. Guy Barnett called for them to be officially recognized for their work. He said, “They carried stretchers, stores and sometimes wounded diggers directly on their shoulders over some of the toughest terrain in the world. Without them I think the Kokoda campaign would have been far more difficult than it was.”

His efforts were successful, and the Fuzzy Wuzzy Commemorative Medallion was created. Beginning in 2009, those still living were gathered with their families for a ceremonial presentation. Despite this, many Australian veterans who received the Fuzzy Wuzzy Angel’s excellent care felt the act was coming far too late to be of any real meaning.

New! Want to become a trivia master? Sign up for our War History Fact of the Day newsletter!

More from us: Fairey Swordfish: The Outdated Biplane That Helped Sink the German Battleship Bismarck

The last of these brave men to serve in Kokoda, Faole Bokoi, died in 2016. Havala Laula, the last of them all, died the following year.