When considering guns and the colonization of the West, violence often springs to mind. Yet, the hidden asset of the Lewis and Clark Expedition was an air rifle that was crucial in the exploration of the American West. Known officially as the Girardoni air rifle, it had the potential to be a strong weapon, but remarkably, it was never used to cause harm to any person throughout the famous 1800s expedition.

Origins of the Girandoni air rifle

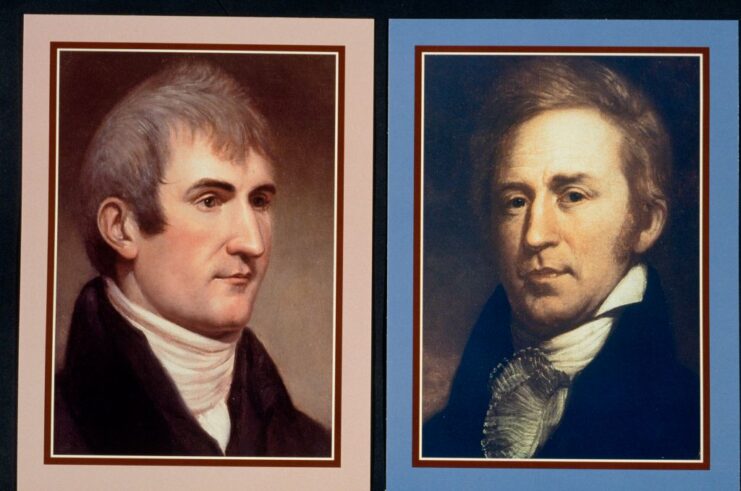

The air rifle employed by Capt. Meriwether Lewis and 2nd Lt. William Clark during their expedition was developed in Austria around 1778. Air guns had been a prominent hunting weapon in Europe since the 16th century, prized for their noiseless operation and lack of smoke when fired.

In 1778, Austrian gunsmith Bartolomeo Girandoni advanced the early air gun designs to create what would become the Girandoni air rifle. This model featured innovations that transformed it from a hunting tool into a military firearm.

The Girandoni air rifle was breech-loading and featured a 20-round tubular magazine along the barrel. Loading was simplified as the user could elevate the muzzle and use a spring-loaded slider to position a ball into place. This design allowed riflemen to load the weapon while lying down, a major advantage over traditional rifles that required standing.

Additionally, the rifle used compressed air rather than gunpowder for firing. The air reservoir was pressurized to around 800 pounds per square inch—much higher than the 35-40 pounds per square inch found in modern car tires.

A fully charged pressure flask was good for up to 30 shots before needing to be recharged.

Service with the Austrian Army

The Girandoni air rifle was in service with the Austrian Army from 1780-1815. The military initially adopted it because of its high rate of fire, low muzzle report and the lack of smoke it produced. However, it eventually fell out of use.

The first notable disadvantage was that to get it fully charged with pressurized air, 1,500 strokes of a hand pump were required. Not only was this practice time-consuming, but it also meant that, if the air pump was lost or damaged, the weapon was useless.

Another major disadvantage was that the air rifle required extensive training to be used optimally because it was so different from any other weapon at the time. Finally, the Girandoni air rifle was very expensive. Each one had to be crafted by master gunsmiths, which took both time and money. It’s estimated that probably no more than 1,300 were produced because of this.

While the air rifle eventually fell out of service, it was still history-changing. It was the first repeating rifle to enter into general military service and one of the first rifles to use a tubular magazine.

Origins of the air rifle used on the Lewis and Clark Expedition

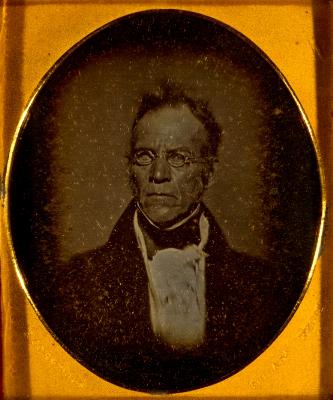

In 1804, Meriwether Lewis wrote that he had purchased an air gun, but didn’t allude to where or from whom he’d purchased it. Historians have debated between two possibilities: that the weapon was made in America and later sold to Lewis or that it was actually the Girandoni air rifle, which was manufactured in Europe and somehow brought to the United States.

Initially, the conclusion was that Lewis had purchased the air rifle from Isaiah Lukens of Philadelphia, who either made it himself or had his father, Seneca Lukens, craft it. In 1846, 40 years after Lewis and William Clark returned from their expedition, an auctioneer’s pamphlet advertised the sale of Lukens’ possessions. This included several air guns, canes and a “large air gun made for and used by Messrs Lewis & Clark in their exploding expeditions. A great curiosity.”

It should be noted that the pamphlet never states Lukens made the rifle himself. As well, in 2002, gun historian Michael Carrick determined that he wasn’t known to have been in business in Philadelphia prior to 1814. In 1803, when Lewis bought it, Lukens was still an apprentice to his father in Horsham Township, located 15 miles north of Philadelphia.

Historians now believe Lewis took a Girandoni air rifle on his expedition. An Austrian government report from January 20, 1801, states that 399 had been lost in battle, meaning there’s an increased possibility of the higher transfer of air guns in Europe and America. Furthermore, while there are no descriptions of the air rifle provided by Lewis, other eyewitness descriptions appear to have major similarities to the one produced by Girandoni.

How did Meriwether Lewis and William Clark use the air rifle?

Regardless of how Meriwether Lewis acquired his air rifle, it became an essential tool in his expedition with William Clark. The Lewis and Clark Expedition moved across the newly-acquired western portion of the United States after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. The purpose was to explore, chart and map this new territory.

Lewis didn’t see his air rifle as a weapon; rather, he saw it as a way to impress the various Native American tribes they’d likely encounter on their journey. In fact, the Lewis and Clark air rifle is mentioned at least 39 times in journals written during the expedition.

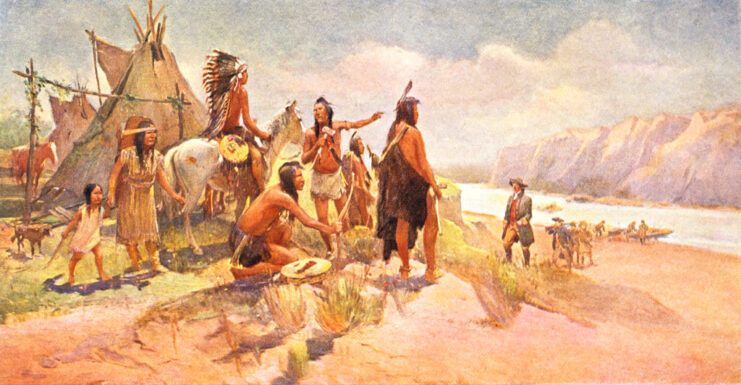

When the men involved in expedition encountered Native Americans, they did their best to impress them through pomp and ceremony. Lewis and Clark often wore their most colorful military uniforms, with their flags flying and fifes whistling. They’d meet with the group and proceed to hand out different gifts, including colored cloth, commemorative medallions and beads.

At some point during this “ceremony,” Lewis would take out his air rifle and shoot it a few times, confident he’d impress his audience.

Impressed by the air rifle

Take, for example, the reaction of the Teton Sioux, who witnessed Meriwether Lewis fire his air gun in a ceremony held on August 30, 1804. The diary account by Joseph Whitehouse, who served as a tailor on the Lewis and Clark Expedition, states:

“Captain Lewis shot his air gun and told them there was medicine in her and that she would do great execution. They were all amazed at the curiosity and soon as he had shot a few times, they all ran hastily to see the ball holes in the tree. They shouted aloud at the site of the execution, they were all amazed at the curiosity.”

Native Americans were likely impressed by the rifle because it was a technology they hadn’t yet seen. The gunstock reservoir was pumped up before the ceremony, meaning there was hardly any evidence that the weapon’s power was man-made. There was no ramming of the ball into the barrel, no primer in the pan, no flash when fired, no smoke produced and several bullets were able to be shot without a pause for reloading.

Perhaps it was for this reason – the curiosity and wonder surrounding the air rifle – that the expedition could pass through Native American villages safely. However, as air rifle and Lewis and Clark expert Robert Beeman points out, “We must avoid the very misleading thought that the Girandoni rifle opened or won the West. Rather, it was the key to Lewis and Clark returning alive and promoting the West.”

Intimidation and close calls

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark’s air rifle wasn’t just used to impress Native Americans – it was also used to intimidate them. One such instance occurred on April 3, 1806, along the banks of the Columbia River, near modern-day Portland, Oregon. Clark wrote that canoes of men, women and children came into their camp. There were about 37 people there at one time, so Lewis fired his weapon, which “astonished them in such a manner that they were orderly and kept at a proper distance during this time.”

There was only one instance in the entire three-year expedition that the air rifle was nearly used in the way it was intended. On August 11, 1806, Lewis was struck by a stray bullet in the leg and believed they were being ambushed. In response, he grabbed both his regular weapon and his air rifle to protect himself. However, the stray bullet had come from one of his own men, rather than a surprise ambush, and the rifle continued to be used for ceremonial purposes only.

Coincidentally, this was the last mention of it in expedition journals.

When the expedition ended in late August 1806, Lewis and Clark returned home, feeling excited about their successful mission. Soon after, however, the air rifle disappeared. For over a century, historians only had descriptions from the expedition journals, and it wasn’t until recently that the rifle reappeared, seemingly out of thin air.

Rediscovering the air rifle used on the Lewis and Clark Expedition

When it came to the attention of historians that Meriwether Lewis had carried an air rifle, their initial guess was that it must have been powered by a ball-shaped tank suspended beneath the gun’s breach. This design was used in many popular sporting air guns made in Europe during the 18th century.

It wasn’t until 1977 that gun historian Henry M. Stewart, Jr. discovered the auctioneer’s pamphlet for Isaiah Lukens’ estate. This gave historians more direction regarding the type of weapon they should be looking for. Enter Robert Beeman in 2004.

Beeman, an expert on air guns, was contacted by master gunsmith Ernie Cowan, who wanted to duplicate a Girandoni weapon in his collection. When Cowan and his collaborator, Rick Keller, disassembled the rifle, they found evidence of previous repairs done to the weapon. They then contacted Michael Carrick, who confirmed this work corresponded precisely to entries in the expedition journals.

More from us: Bell P-39 Airacobra: World War II’s Most Controversial Low-Altitude Fighter

Want to become a trivia master? Sign up for our War History Fact of the Day newsletter!

Beeman, who recognized the historical significance of the air rifle, donated the weapon to the permanent collection of the US Army War College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.