During the Second World War, the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) built numerous impressive warships, with the IJN Shinano being particularly notable. Originally planned as a Yamato-class battleship, strategic adjustments led to her conversion into an aircraft carrier in response to substantial losses suffered by the Japanese fleet at the Battle of Midway.

Construction of the IJN Shinano

The IJN Shinano’s construction started on May 4, 1940, at the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal. Initially progressing without issue, a key moment in 1942 saw the battleship being redirected to become an aircraft carrier. This shift was prompted by Japan’s losses against the Americans.

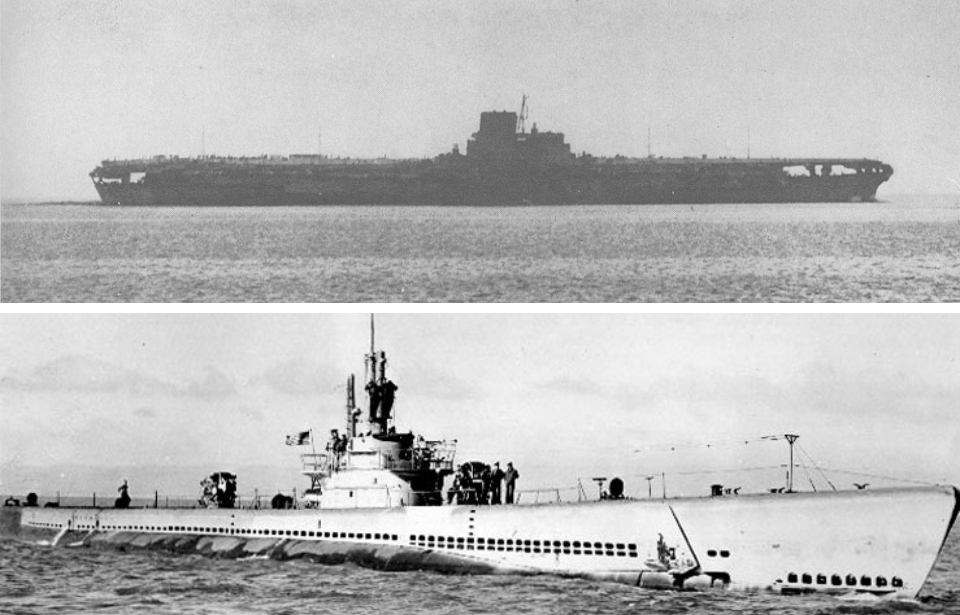

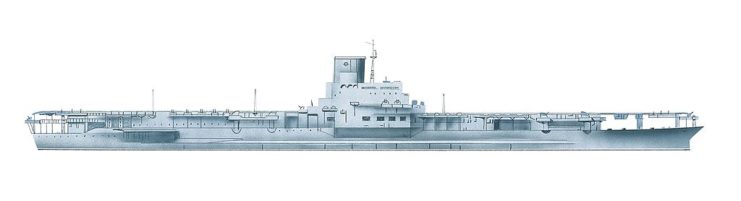

Rather than becoming a fleet carrier, Shinano was converted into a 65,800-ton, heavily armored support carrier designed primarily for reserve aircraft and fuel storage.

The construction of Shinano was shrouded in strict secrecy, safeguarded from public view by a high fence around the building area. Workers involved in the project were required to maintain absolute confidentiality, with the risk of execution for any leaks.

As a result, Shinano is the only major 20th-century warship without any construction photographs. Even after completion, the ship was filmed just twice: once by a Boeing B-29 Superfortress during reconnaissance and once by a civilian during sea trials.

Armor and armament

The IJN Shinano underwent modifications influenced by the design of the design of the Yamato and Musashi. Originally planned to have slightly thinner armor by 10-20 mm and fitted with newer anti-aircraft guns, these specifications were altered when she was repurposed into an aircraft carrier. Consequently, Shinano diverged significantly from the typical appearance of a Yamato-class ship, shedding a considerable portion of her armor and large main guns.

In her new form, Shinano took on the characteristic flat top of aircraft carriers and a streamlined flight deck.

Shinano boasted impressive dimensions, measuring 872 feet in length, with a beam of 119 feet and a draught of nearly 34 feet. Her power source consisted of 12 Kampon water boilers, driving four geared steam turbines, which in turn propelled an equal number of shafts, producing 150,000 shaft horsepower. Under optimal conditions, this setup enabled the aircraft carrier to achieve a surface speed of approximately 27-28 knots.

Traveling toward certain destruction

Initially slated for commissioning in early 1945, the construction schedulefor the IJN Shinano was expedited following the Battle of the Philippine Sea. The engagement inflicted major losses on the Japanese Navy, including two fleet carriers, one light carrier and two oilers, with several smaller vessels sustaining damage.

The accelerated construction of Shinano resulted in compromised workmanship on later components. Despite this, she was launched on October 8, 1944, and commissioned on November 19 of the same year.

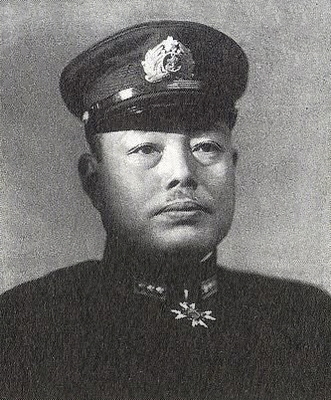

Following her commissioning, Shinano was scheduled to transit from her shipyard to Kure Naval Base, where she’d be armed and receive aircraft under the command of Capt. Toshio Abe. Despite pressure from superiors to depart immediately, Abe requested a delay, due to incomplete bailing pumps and fire mains. Unfortunately, his plea was denied, and he was forced to set sail at night, contrary to his preference for a daytime departure.

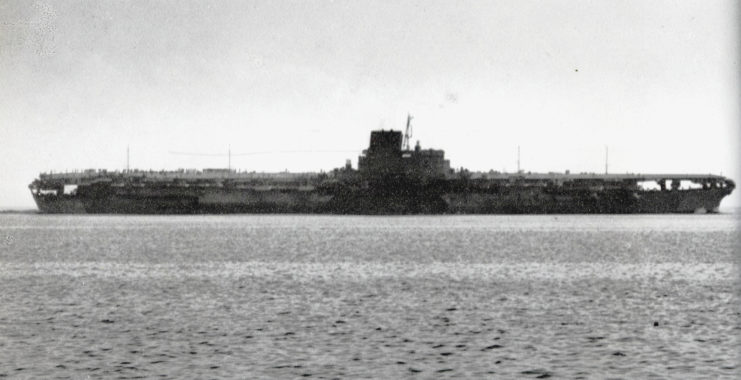

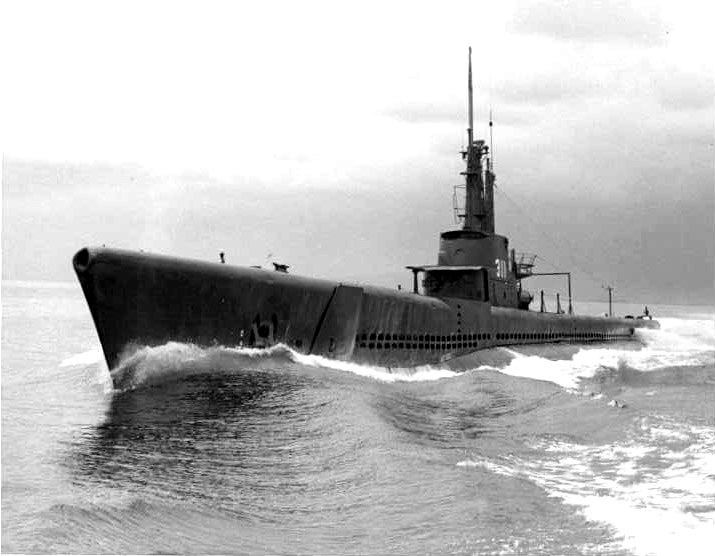

Leaving at 6:00 PM on November 28, 1944, Shinano was accompanied by Isokaze, Yukikaze and Hamakaze. While en route, the ships detected radar signals that indicated the presence of an American submarine nearby, prompting them to employ evasive maneuvers. Unbeknownst to the crew, these inadvertently placed Shinano directly in the path of the USS Archerfish (SS-311).

Sinking of the IJN Shinano

The USS Archerfish, under the command of Cmdr. Joseph Enright, had clocked the IJN Shinano two hours before the submarine was noticed by the Japanese aircraft carrier. Abe, believing they’d encountered an American wolfpack, ordered his ships to turn away from Archerfish, in an attempt to outrun the submersible. This would have worked, as Shinano was the faster out of the two, but she was forced to reduce her speed to prevent damage to the ship.

By 2:56 AM on November 29, Abe had changed direction to move toward the submarine, only to turn southwest, exposing the entire side of the ship to Archerfish. At 3:15 AM, Enright made the call to fire six torpedoes at their target, ensuring the first two hit before diving to a depth of 400 feet to wait it out.

Four of the torpedoes hit Shinano, which was enough to sink her. Enright and his crew didn’t know what ship they’d sunk until the Second World War was over, nor that it took over seven hours for the aircraft carrier to go down.

Hindsight is 20/20

Initially, those aboard the IJN Shinano underestimated the severity of the damage caused by the torpedo strikes, meaning minimal effort was made to salvage the ship. Abe, in particular, directed her to maintain maximum speed, inadvertently accelerating the flooding of the aircraft carrier.

Unfortunately, by the time they grasped the gravity of the situation, it was too late. The ship had become too heavy to be towed by escort vessels, too inundated to be pumped out and too irreparably damaged for the majority of her crew to evacuate. Out of her 2,400-man crew, 1,435 perished with the ship, including Abe and both navigators.

The survivors were sent to Mitsukejima until January of the subsequent year, preventing the widespread dissemination of news about Shinano‘s sinking. Following the conclusion of the war, the US Navy analyzed the aircraft carrier, along with other Yamato-class ships, and identified significant design flaws that rendered specific joints susceptible to leakage. It was concluded that the torpedoes from the USS Archerfish happened to strike these vulnerable joints, contributing to Shinano‘s demise.

Are you a fan of all things ships and submarines? If so, subscribe to our Daily Warships newsletter!

Regarding Enright, US Naval Intelligence initially doubted his claim of sinking a Japanese carrier, believing all had been identified. However, this was rectified after the war, and Enright was duly honored with the Navy Cross for his victorious achievement.