During the Second World War, Japanese kamikaze pilots gained notoriety for their self-sacrificial bombing tactics, intentionally converting their aircraft into human-guided bombs and willingly sacrificing their lives to target enemy naval vessels. In contrast, their German counterparts are relatively less recognized.

Emerging toward the end of the conflict, as Allied aerial bombardments intensified, these individuals were known as the Sonderkommando “Elbe.”

Allied air raids over Germany

What compelled the Luftwaffe to establish this force? Sheer desperation. By 1944, the Allies had intensified their bombing campaigns over Germany, aiming to weaken the enemy’s forces, disrupt production efforts and undermine morale. In the following year, a multitude of aerial attacks ensued.

In Dresden, the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the US Army Air Forces (USAAF) joined forces, assembling a formidable fleet of 1,200 bombers for four devastating assaults, resulting in the loss of over 25,000 lives. Shortly after, an RAF contingent of over 1,000 bombers targeted Essen, while the USAAF focused on bombing German railways. This was followed by an extended assault on Berlin, where 1,221 Allied bombers, accompanied by support fighters, prevailed over the defending Luftwaffe.

These instances represent just a glimpse of the numerous air raids launched by the Allies as the Second World War approached its conclusion, with many other aerial forces penetrating deep into Germany to strike airfields.

Forming Sonderkommando ‘Elbe’ as a last-ditch effort

In response to these attacks, the Luftwaffe made a strategic decision to establish an unconventional unit, the Sonderkommando “Elbe,” under the leadership of Oberst Hans-Joachim “Hajo” Herrmann, a German pilot. Recruitment for this specialized force commenced toward the latter part of 1944, with an emphasis on minimal training, as the pilots only required rudimentary skills for takeoff and aircraft control.

Herrmann looked for volunteers within the 18-20 age range who were prepared to carry out ramming missions against the vulnerable areas of Allied bombers. If possible, they’d parachute to safety, but there was a significant risk of these missions becoming deadly endeavors.

Most of the volunteers had been exposed to wartime German propaganda during their formative years and they were willing to make the ultimate sacrifice for their perceived cause. The unit’s motto underscored this, translating to “loyal, valiant, obedient.”

Flying the Messerschmitt Bf 109G

Herrmann’s goal for Sonderkommando “Elbe” was to put enough of these pilots in the air to cause the Allies to withdraw their bombers and regroup for a few months, allowing the Luftwaffe to do the same. To do so, they used the Messerschmitt Bf 109G, one of the most commonly-flown German aircraft.

Compared to normal Bf 109s, those flown by Sonderkommando “Elbe” were stripped of most hardware, to make them lighter, faster and easier to maneuver. They had little armor and weaponry, except for a single machine gun, usually an MG 131. Typically, the Bf 109G was equipped with four automatic weapons. In addition, the pilots were only given 60 rounds per mission, with the rationale being that, on a suicide run, they wouldn’t need more.

The one and only mission of Sonderkommando ‘Elbe’

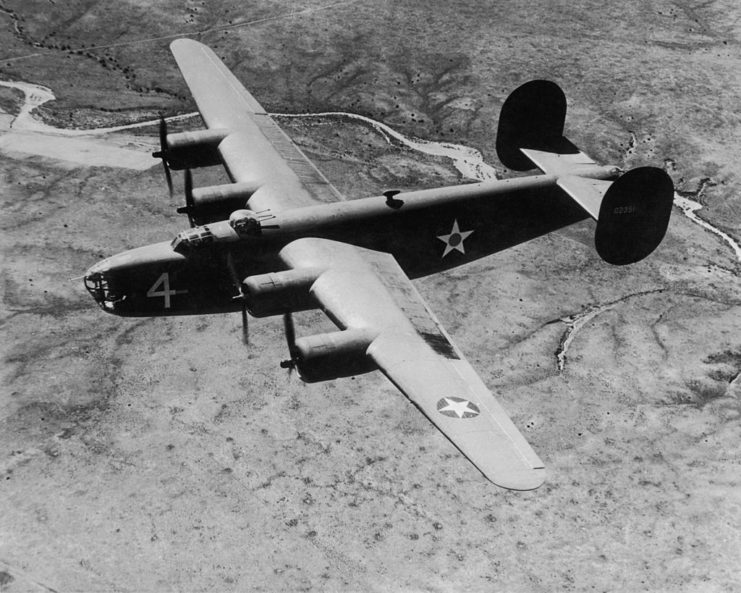

Despite Herrmann’s desire to put together a large force, Germany simply didn’t have access to enough fuel. Instead, he ended up with 180 pilots, who were deployed on their first – and last – mission on April 7, 1945. On this day, the Allies left England with a force of 1,300 Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses and Consolidated B-24 Liberators, on their way to attack oil and arms factories near Hamburg, as well as German airfields.

Out of the ordinary, however, was that they were met by the full force from Sonderkommando “Elbe.” The Luftwaffe‘s plan was to have their force of Messerschmitt Me 262s engage the Allied fighters, while the Bf 109Gs attacked their larger targets. Of the 180 pilots deployed, 120 successfully engaged the bombers. Of those, only 15 rammed their targets, and only eight Allied aircraft were destroyed.

Although the numbers were low, the initial effect Sonderkommando “Elbe” had on the Allies was immense. The bombers had no way of knowing they would encounter German kamikaze pilots. Once they realized what was going on, the plan no longer had the same effect. Both the bombers and accompanying fighters simply shot down any aircraft they believed were trying to hit them.

Notable Sonderkommando ‘Elbe’ takedowns

While the overall deployment of Sonderkommando “Elbe” was a failure, they achieved a number of successes throughout the assault on April 7, 1945. Unteroffizier Heinrich Rosner took out the lead B-24, Palace of Dallas, of the 389th Bombardment Group (Heavy) and survived bailing out of his Bf 109G. Similarly, pilot Heinrich Henkel took out the B-24 Sacktime.

The other pilots, however, were much less successful. Leutnant Hans Nagel shot down a B-17 from the 490th Bombardment Group, but was killed while ramming a second. Fähnrich Eberhard Prock also hit a B-17 and was able to bail out. However, one of the Allied North American P-51 Mustang pilots shot and killed him before he made it to the ground.

More from us: The Real-Life Men Behind the Characters of ‘SAS: Rogue Heroes’

Want War History Online‘s content sent directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter here!

Ultimately, the attack was a massive failure for the Luftwaffe, with the Allies destroying over 300 German aircraft. The following week, they took out an additional 700. Sonderkommando “Elbe” never flew again due to high losses of both pilots and aircraft.