Toward the final stages of World War II, both Allied and Axis powers crafted more and more complicated strategies to bring the war to an end. For example, the Americans devised Operation Downfall, an ambitious campaign aimed at invading the Japanese mainland. In retaliation, the Japanese employed innovative defenses such as kamikaze frogmen and manned torpedoes.

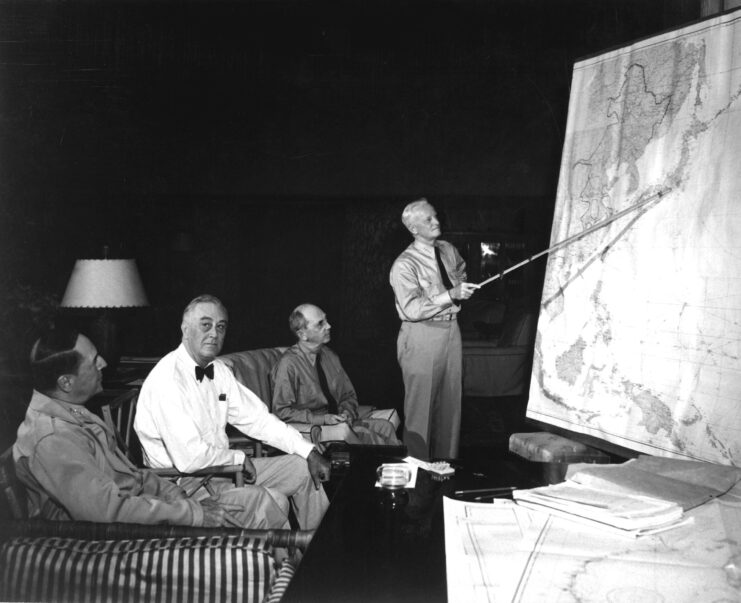

Operation Downfall

Operation Downfall was the American plan to invade and conquer Japan. It was set to unfold in two phases: Operations Olympic and Coronet. If executed, it would have been a larger amphibious invasion than D-Day.

The operation was scheduled to begin in November 1945, following the end of the war in Europe. The first phase, Olympic, would begin with a massive amphibious assault on the Japanese island of Kyūshū, which would then serve as a staging ground for future troops during Coronet. This second phase, planned for around March 1946, would target Tokyo Bay with an even larger force.

However, the planned invasion was never carried out, as Japan surrendered following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This spared both sides the catastrophic casualties that such an invasion would have entailed.

Training kamikaze frogmen

Anticipating an impending Allied invasion, the Japanese developed the Fukuryu tactic as a defensive measure. Meaning “crouching dragon,” this strategy involved kamikaze frogmen launching surprise assaults on enemy vessels from below the water.

Captain Kiichi Shintani of the Yokosuka Naval Base Anti-Submarine School in Japan first proposed this idea in 1944. Faced with a shortage of personnel and resources that made traditional defenses ineffective, he adapted tactics from past battles like Peleliu.

These operatives would hide underwater at key points along Japan’s coastline, carrying out stealthy explosive attacks under the cover of darkness to ambush enemy forces. This approach reduced their visibility and decreased the chances of being spotted or facing counterattacks.

Fukuryu attacks

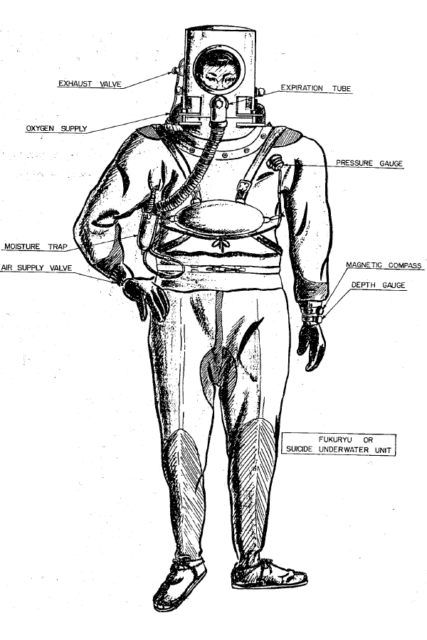

These kamikaze frogmen would emerge from their underwater hideouts in diving suits, armed with 16-foot bamboo spears fitted with Type-5 attack mines. Each contained 33 pounds of explosives and was designed to detonate when pushed against the hull of an overhead ship.

Multiple explosives were placed around these underwater hideouts for easy access by the frogmen. Due to the mission’s nature, those trained for this task weren’t expected to survive, if they were successful. They faced not only a one-way journey, but also endless, lonely hours awaiting the enemy’s arrival.

Training the kamikaze frogmen

Nevertheless, extensive preparations were undertaken to train 6,000 kamikaze frogmen for this role, which required a large amount of specialized equipment. Each frogman would be equipped with a diving suit, comprising a jacket, pants, shoes, and helmet, along with provisions of oxygen and liquid sustenance to endure approximately 10 hours submerged. Furthermore, they would be laden with 20 pounds of lead at depths ranging from 16 to 23 feet.

In addition to outfitting each operative, there was also the need to establish subterranean hideaways where they could patiently wait for approaching enemy vessels. The chosen solution involved constructing large concrete structures above ground, to later be submerged to their designated positions, though this plan was never executed. An alternative proposal considered underwater steel foxholes, but this concept was swiftly discarded due to its potential interference with nearby explosives.

Despite the clear meticulous planning by the Japanese to deploy their kamikaze frogmen, they ultimately stayed unused.

A failed initiative

The 71st Arashi were trained at Yokosuka, while the 81st Arashi would undergo training at Kure. Another unit was in the works at Sasebo. However, there were only two battalions fully trained by the time the Japanese surrendered, both with the 71st. The total equaled about 1,200 of the proposed 6,000 frogmen.

Training wasn’t the only thing falling behind, as production also proved difficult. Only 1,000 diving suits were ready at the time of surrender, and none of the real mines were constructed, only dummy ones.

Even though the Fukuryu were never used in combat, many still died during the training. Most of these fatalities were caused by issues with the breathing apparatuses in the diving suits. They were rudimentary, so each diver had to inhale through their nose and out through their mouth into a tank, which would turn the carbon monoxide back into oxygen.

If they mixed the two up, they’d inhale caustic lye and faint while underwater. If any seawater got into the tanks, a mixture was created that, when inhaled, would burn the lungs.

Want War History Online‘s content sent directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter here!

Other divers died when they got tangled in plant life on the ocean floor and were unable to free themselves. Ultimately, no enemy combatants were ever killed in Fukuryu attacks, yet so many trainees were that “they couldn’t keep up with cremation.”