The efforts at Bletchley Park in Buckinghamshire are hailed for reducing the duration of World War II by two to four years. The brightest minds in the UK labored relentlessly to crack the German Enigma Code and codes from other Axis powers. What many might not know is that a large portion of those performing this crucial task were women.

Bletchley Park’s top secret mission

Bletchley Park’s mission was once one of the world’s best-kept secrets. Breaking the German Enigma Code and Lorenz ciphers played a key role in the UK’s fight against Germany. It helped the Allies score war-changing wins in Europe – and later the Pacific – giving them a necessary edge against the Germans.

Those chosen to work at Bletchley Park often had no idea what they were signing up for. The hiring process was secretive, and each new hire was made to sign the Official Secrets Act (1939). Only when they arrived in Buckinghamshire did they learn their task was to decipher the code the Germans believed was unbreakable.

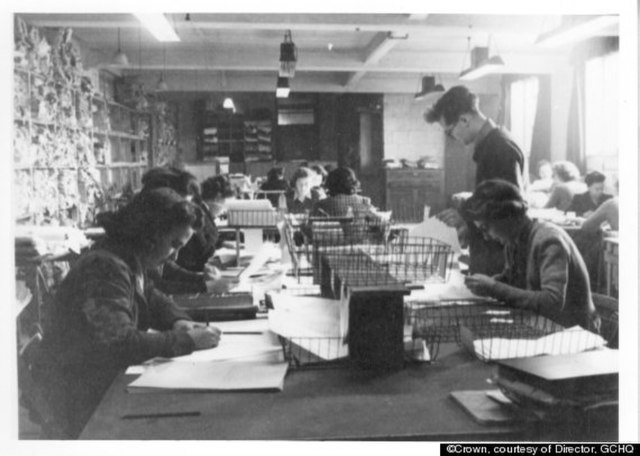

Around 10,000 personnel were working at Bletchley Park and its outstations by January 1945

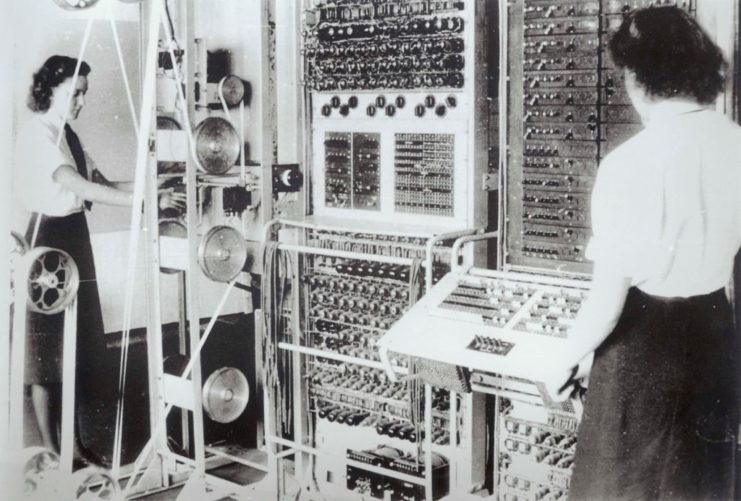

The Government Code and Cypher School managed the project. Each person had specific responsibilities, carried out in huts scattered across the sprawling estate. They employed cutting-edge technology, including the Bombe machine, to decipher codes, and by January 1945, it’s estimated that 10,000 personnel were stationed at Bletchley Park and its associated locations.

The efforts at Bletchley Park remained classified until 1974, preventing workers from sharing their wartime achievements with their families. By the time the files were made public, many had already died without witnessing their efforts and dedication acknowledged.

Women played a key role

While the most well-known codebreakers at Bletchley Park were Alan Turing and Stuart Milner-Barry, the vast majority of those working there were women. With much of the country’s men fighting in Europe, the GC&CS needed to expand recruitment.

Approximately 75 percent of those working at Bletchley Park by the end of the war were women. They were largely university educated and from families of high social standing, but later grew to include crossword enthusiasts, mathematicians and linguists.

A complete list of workers was never produced

While women were first charged with performing clerical duties, their mandate was later expanded to include the codebreaking typical done by male cryptanalysts. They were soon operating the Bombe machines and Colossus computers, considered the most important of auxiliary work. While many of their male colleagues initially believed them incapable, they soon proved themselves to be up for the task.

There have been many efforts to commemorate the women who worked at Bletchley Park. Unfortunately, the task has been made difficult by the fact a complete list of workers was never produced. This means the current roster has been compiled by friends, family, veterans, and other sources.

Alisa Maxwell

Alisa Maxwell had initially planned to join the Women’s Royal Navy Service (WRNS) when she was approached by the Foreign Office to interview for an unspecified job. She was sent to work as a temporary assistant at Bletchley Park, and just two weeks later was assigned to Hut 6, where she worked in the Block D machine room.

Maxwell was responsible for compiling information obtained by other huts and inputting them into the Bombe machine. Her most significant accomplishment came on May 7, 1945. While working alongside Intelligence Corps member Asa Briggs, her station received an uncoded message from Admiral Karl Dönitz, the German Führer‘s successor and President of Germany, announcing the country’s unconditional surrender.

Helene Aldwinckle

Helene Aldwinckle was recommended by Aberdeen University Principal William Hamilton Fyte, in part due to her memory and interest in languages. She was selected by Stuart Milner-Barry to become a permanent Foreign Office Civil Servant and sent to Bletchley Park in the summer of 1942.

She was initially placed in Registration Room 1 (RR1) and tasked with training American service personnel. When that work was complete, she was transferred to the Quiet Room (QR) in Hut 6 to decipher the Enigma codes. Her work with Americans came in handy, as it allowed her to work on longer, more complicated encryption problems, including the identification of Enigma radio signals and networks.

Aldwinckle stayed at Bletchley Park after the war to help write up the history of Hut 6. However, she was forced to leave in 1945, due to a Foreign Office policy stating women could not stay employed after marriage. Just a few months earlier, she’d wed Royal Air Force lieutenant John Aldwinckle.

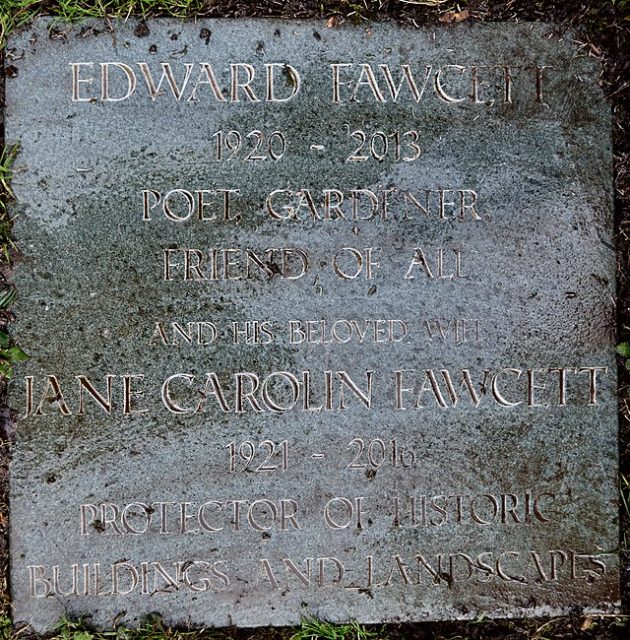

Jane Fawcett

Jane Fawcett joined Bletchley Park in 1940, after being interviewed by Stuart Milner-Barry. She was known as one of the “Debs of Bletchley Park,” due to her family’s status. She was assigned to Hut 6, a decoding room made up solely of women. There, she and her colleagues received daily Enigma keys, which they typed into their Typex machines to determine if they were recognizable German.

Through her work, she was able to help decode a message regarding the position of the German battleship, Bismarck. She and the team learned it was sailing to France, allowing the Royal Navy to attack and sink it on May 27, 1941. This is widely considered the first significant victory for the codebreakers at Bletchley Park.

Margaret Rock

Margaret Rock joined Bletchley Park on April 15, 1940, where she worked for Admiral Sir Hugh Sinclair, the Head of the GC&CS and the Secret Intelligence Service. Her education – specifically her math skills – enabled her to decode German Enigma alongside some of the best, including Alfred Dillwyn “Dilly” Knox, the Chief Cryptographer of the GC&CS.

While working with Knox, Rock became the most senior cryptographer, specializing in German and Russian codebreaking. Her biggest accomplishment came when she and her team decoded a message that gave the British forces the advantage when it came to planning the D-Day attacks.

Mavis Batey

Mavis Batey is widely considered one of the leading codebreakers of Bletchley Park. Initially stationed at one of its outstations in London, she was later transferred to the Buckinghamshire estate, where she worked as an assistant to Dilly Knox.

Want to become a trivia master? Sign up for our War History Fact of the Day newsletter!

Batey quickly adapted to her new work environment and became familiar with the different styles of individual enemy operators. In late March 1941, she was working on Italian Naval Enigma when she deciphered a message, leading to the discovery that the Italians were planning to attack the Royal Navy supply convoy off the coast of Greece. The subsequent combat became known as the Battle of Cape Matapan.

In December 1941, she broke a message between Belgrade and Berlin that enabled the team to break the Abwehr Enigma. She later broke another, the GGG. It contained messages confirming the Germans were falling for the Double-Cross intelligence being passed on by double agents.