During its peak, Đông Hà, the northernmost city in South Vietnam, was a hub of military activity. It hosted the 4th Marine Division and a helicopter base and was surrounded by artillery fire bases that played a key role in supporting troops at Con Thien and the Eastern Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). Furthermore, the city was a strategic launchpad for relief missions at the Khe Sanh garrison and was home to a bridge spanning the Cửa Việt.

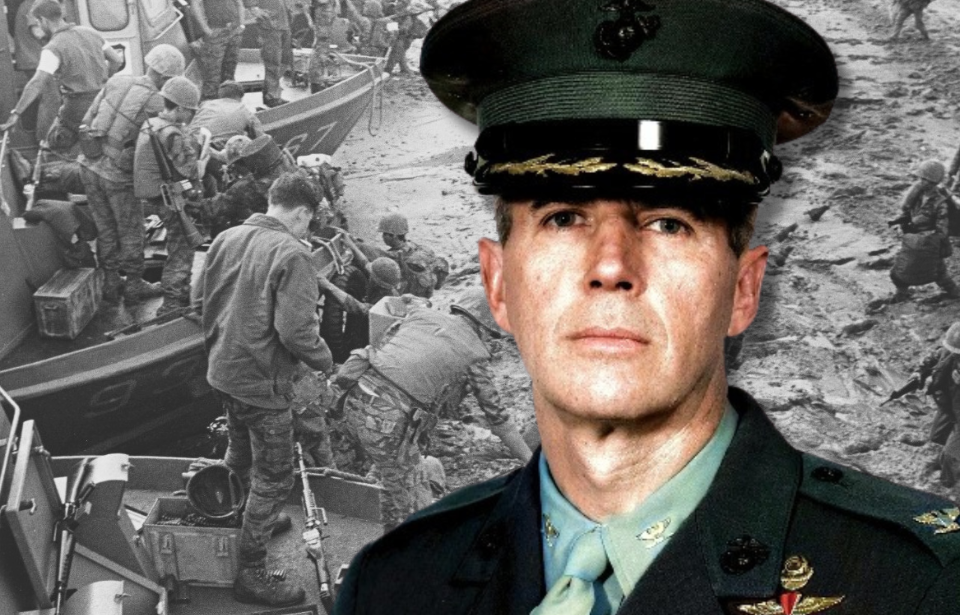

John Ripley had a lifetime of preparation

John Ripley was a daring child, driven to excel. Following in the footsteps of his two older brothers, he enlisted in the US Marine Corps upon graduating from high school in 1957. The formidable training regimen at the renowned Marine Corps Recruit Depot, Parris Island honed his ambition into an unstoppable force.

Recognizing Ripley’s talent and tenacity, he secured a coveted spot at the US Naval Academy, despite facing academic challenges. Through sheer perseverance, he earned a degree in electrical engineering and was commissioned as a second lieutenant in 1962.

At the Basic School in Quantico, Virginia, Ripley immersed himself in learning the art of leading an infantry platoon. Following graduation, he assumed roles as a rifle and weapons platoon commander, as well as a force reconnaissance platoon commander. His thirst for knowledge and adventure led him to pursue further training, with him attending the US Army’s Parachute, Jump Master and Ranger courses, alongside the US Navy’s Underwater Demolitions and Scuba courses.

Within Marine circles, Ripley earned distinction as “dual cool,” adorned with both a Scuba Badge and Jump Wings, emblematic of his multifaceted expertise and remarkable dedication.

Ripley’s Raiders and the British Royal Marines

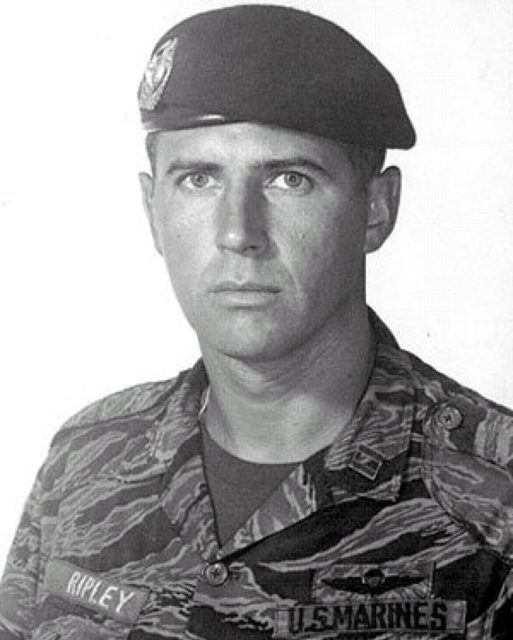

In October 1966, John Ripley assumed command of “Ripley’s Raiders,” leading them in combat at both Con Thien and Khe Sanh. Despite sustaining four wounds, he declined multiple Purple Hearts due to the policy of immediate evacuation for such injuries at the time.

Following his service in Vietnam, Ripley became an exchange officer with the British Royal Marines. After successfully completing the Commando Course, he became only the third person to accomplish a “quad bod” – completing training in Jump, Ranger, Navy SEAL and Commando programs – and was awarded the Green Beret of the Royal Marines.

Leading troops in both the Royal Marines and the Royal Navy’s Special Boat Service (SBS), Ripley undertook missions in Malaya and Norway. Despite being assigned to a desk job at Headquarters Marine Corps in late 1971, he volunteered for redeployment to Vietnam.

John Ripley joined the Vietnamese Marine Corps

John Ripley stood among the dwindling number of US Marines stationed in Vietnam, his extensive preparation about to be put to the ultimate test. Serving as a senior advisor with the 3rd Battalion of the Vietnamese Marine Corps, his combat expertise was invaluable at a time when the Vietnamese Army was unprepared.

From the over 500,000 troops in 1968, the US presence in Vietnam had dwindled to just 27,000. The South Vietnamese forces struggled with poorly trained conscripts and ineffective leadership, resulting in significant setbacks against their Northern counterparts, who stood as their antithesis in almost every aspect.

Yet, amidst this adversity, the Vietnamese Marine Corps stood out. These seasoned fighters were molded by Vietnamese instructors trained at Drill Instructor School at Parris Island and led by officers from the Basic School. Operating as a rapid response unit, they endured up to six months of continuous combat before a month-long rest at their home base. The 3rd Battalion had recently completed its refitting near Saigon and was now operating at full capacity.

A Marine may be outnumbered, but never outfought

On March 30, 1972, the North Vietnamese attacked. Intense artillery from the north of the DMZ was followed by assaults that quickly erased the forces guarding the northern approaches. Those not overrun were sent fleeing down Highway 1.

The 3rd Battalion was shifted to protect the vital bridge that provided passage over the Cửa Việt, at Đông Hà. The 304th and 308th NVA Infantry Divisions were rolling south with 200 main battle tanks. On April 1, the 3rd ARVN Division was ordered to retreat. The North Vietnamese bore down on Đông Hà. As troops streamed south, the Marines were facing an impossible task: fighting 30,000 enemy troops.

Passing hordes of refugees, they moved into their final positions and heard someone say, “Expect lots of tanks,” over the radio. They had with them just 10 light anti-tank rockets, making them almost defenseless. The 20th Tank Battalion arrived, and the Marines clambered aboard for their final movement to the bridge.

The Marines knew they had to stop the enemy from crossing the bridge

Skirmishers were already crossing upstream, over a dilapidated, railroad bridge designed for foot-traffic. John Ripley directed the tank he was in to fire, knocking back the enemy. Machine guns and mortars on the opposite bank immediately began a furious fusillade of fire against the tanks and Marines while the enemy soldiers regrouped behind a small rise that protected them from the tanks.

The small column of Marines riding M48 Pattons continued slowly, surrounded by fleeing civilian refugees. A column of Soviet-supplied T-54s was spotted across the river and taken under fire by the 20th. However, the T-54 outgunned the M48; head on, the remaining ones would slaughter their smaller opponents. The Marines knew they had to get to the bridge first. If their opponents got across, the battle – and, maybe, the war – would be lost.

Ripley’s mad dash

The M48s stopped well away from the bridge. The Marines climbed down and continued on foot. Ripley watched the lead T-54 reach the structure and begin to cross, at which point a Marine with an anti-tank rocket hit the tank. The stricken vehicle pulled back to a covered position.

Under enemy fire, Ripley made a mad dash to an old bunker some 100 meters from his position and 100 meters from the bridge. Accompanying him was his Vietnamese radioman, Maj. Jim Smock, an advisor with the 20th. A vicious firefight began as the pair made their last dash to the bridge, praying there would be a way to bring it down upon their arrival.

Đông Hà Bridge

A bundle of explosives had been delivered, but hadn’t been prepped for use. The bridge was constructed of steel I-beams, overlaid with steel decking and two feet of timber sitting atop six-feet-thick concrete supports. As such, it could only be brought down via demolition.

Since the bridge’s deck was fully exposed to enemy fire, the only way to set the explosives was by hand and from underneath. From beneath the bridge, John Ripley would be able to slide cases of TNT between the edges of the I-beams to a point in the middle of the river and set satchel charges to cut them. There were six I-beams in total, creating five “channels” through which he’d need to drag explosives.

Setting the charges

Once he’d climbed over the fence, Ripley’s legs were shredded by the razor-sharp concertina wire protecting the south end of the bridge. Despite this, he went hand-over-hand under the bridge amid the enemy fire. He finally reached the concrete support 90 meters away, and swung himself up and into the channel created by the I-beams.

Setting charges to cut the beam, Ripley traveled back down the channel. Smock passed him two 75-pound TNT cases and satchel charges, which he dragged back again. He set the charges to cut the other beam – one channel was rigged, but there were still four more to go.

Destroying the bridge

Two hours later, completely spent, all the channels were finally set to detonate. Dropping to the ground and curling into a ball, Ripley rested for only a moment before retrieving primer cord and crimping the blasting caps. He then looped the coils over his shoulders and crawled back out, legs dangling and drawing fire.

Having set the cord alight with matches, Ripley crawled out once more to set a backup detonator with electrical caps. Returning to the bunker seemed to take an eternity, as Ripley’s legs woodenly refused to move quickly. He ran under fire from the other side of the river, and, with a gut-wrenching, earthshaking explosion, the bridge was finally destroyed.

Bitter aftermath

The Marines and South Vietnamese tankers continued to hold Đông Hà. An attack from the west cut through to Highway 1 south of the city, but they continued to fight, despite being surrounded.

One by one, the M48s were destroyed or ran out of gas. Ordered to breakout, the surviving tankers shouldered rifles and joined the Marines. Continuing the fight at Quảng Trị, the 3rd Battalion was finally pulled out of the line. Of the 700 men who’d begun the fight, only 52 remained.

The Easter Offensive was beaten by the North’s inability to capture Đông Hà quickly. Eventually, theys withdrew. Three years later, they returned, this time for good.

John Ripley’s further service in the US Marine Corps

John Ripley remained in the US Marine Corps, eventually commanding an infantry battalion and, then, an infantry regiment. Always attempting to evade a desk job, he finally found one he enjoyed at the US Naval Academy as an English and History instructor. Later on, he was the commander of the Naval Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) unit at the Virginia Military Institute (VMI), in his native Virginia.

Retiring as a colonel in 1992, Ripley accepted a position as the Dean, then, later, as chancellor of Southwestern Virginia College, before moving to the Hargrave Military Academy. He returned to duty in July 1999, to lead the US Marine Corps History and Museums Division. He passed away on October 28, 2008.

More from us: Chuck Mawhinney: The Legendary USMC Sniper Who Hit 16 Enemy in 30 Seconds on a Pitch-Black Night

John Ripley earned the Navy Cross for his heroic actions on the bridge at Đông Hà, but the legacy he was most proud of was having commissioned over 500 young Marines between his time at the US Naval Academy and the VMI.