You’re likely familiar with the famous US Navy SEALs and the Army’s Green Berets, celebrated for their skills in guerrilla and counter-guerrilla tactics, alongside their central roles in training local forces and countering insurgencies during the Vietnam War. Yet, the importance of MACV-SOG should not be understated. This specialized unit effectively merged personnel from these previously mentioned groups with CIA operatives, creating a formidable covert force that executed highly successful secret missions throughout the conflict.

MACV-SOG’s operations covered a spectrum of unconventional warfare activities in Vietnam, including reconnaissance, rescue missions, psychological operations, and the capture of enemy combatants. Their missions deeply influenced the course of the war.

MACV-SOG’s top-secret beginnings

On January 24, 1964, MACV-SOG, officially known as the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group, came into existence. Comprised of operators from the most elite branches of the US military, including Green Berets, Navy SEALs, Air Force Commandos, CIA operatives and veterans of the Marine Corps’ reconnaissance units, the group was an assembly of specialized talent.

Initially, MACV-SOG’s operations in Vietnam were overseen by the Special Assistant for Counterinsurgency and Special Activities within the US Department of Defense. This arrangement granted the authority to conduct missions beyond the borders of South Vietnam. Eventually, control of the group was transferred to the military.

A significant portion of MACV-SOG’s missions occurred within North Vietnam, and the utmost secrecy was imperative. This discretion was necessitated by the official American stance that the US forces were confined to operations within South Vietnam. Additionally, the group dedicated efforts to missions in Laos and Cambodia, due to the strategic significance of the Ho Chi Minh Trail, which played a crucial role in supporting the North Vietnamese Army (NVA).

Given the exceptionally perilous nature of their tasks, MACV-SOG was exclusively composed of volunteers. The hazardous conditions were so pronounced that the casualty rate for operatives stood at a staggering 100 percent; they understood their service would likely culminate in either receiving a Purple Heart for their valor or returning home in a flag-draped casket.

Unidentifiable Americans

Due to the sensitive nature of their operations, MACV-SOG followed strict uniform guidelines aimed at blending in seamlessly with South Vietnamese forces. They wore the distinctive tiger stripe camouflage typical of their allies and avoided any visible identification such as dog tags or patches. Similarly, the Green Berets opted not to wear their trademark headgear.

In terms of armament, MACV-SOG operatives typically carried either a CAR-15 or an AK-47, along with M79 grenade launchers. Notably, all identifying serial numbers on these weapons were deliberately removed to prevent identification. Each weapon was meticulously secured to minimize noise during movements; rifles were slung with a canvas strap, while M79s were fastened with a tape-covered D-ring.

Beyond firearms, operators also carried additional weaponry like fragmentation grenades and V40 mini grenades, reflecting the unorthodox nature of their missions. For instance, Staff Sgt. Robert Graham, a MACV-SOG member, creatively used a 55-pound bow equipped with razor-edged arrows when conventional ammunition was scarce.

Ho Chi Minh Trail

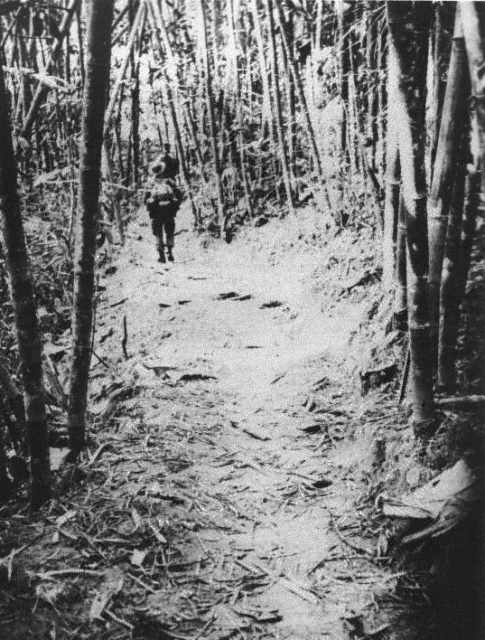

The primary theater of action for MACV-SOG was the Ho Chi Minh Trail, recognizing its strategic importance in countering guerrilla activities. Within this theater, the group served as critical field operatives, gathering intelligence for Saigon through tasks like reconnaissance, document retrieval, and interception of enemy communications.

These missions were inherently dangerous, needing substantial support from local forces who made up the majority of each unit. Typically, teams consisted of two to four American personnel working alongside four to nine South Vietnamese guerrillas.

Jim Bolen, in an interview with History of MACV-SOG, highlighted the complicated nature of missions along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, emphasizing their alignment with key routes within the network. These paths often skirted large enemy encampments housing thousands of soldiers.

Such challenges were vividly illustrated in notable missions, such as the Thanksgiving Day 1968 operation where a six-man team confronted a formidable enemy force numbering 30,000. Similarly, Frank D. Miller’s lone encounter with 100 NVA troops showed the serious risks involved.

MACV-SOG operations behind enemy lines

During an interview with the History of MACV-SOG, Jim Bolen disclosed that he and his team were assigned the duty of deploying seismic sensors along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. These sensors were monitored by Lockheed C-130E Blackbirds, providing early alerts of important enemy movements.

It is widely acknowledged that thanks to this and other intelligence-gathering endeavors, MACV-SOG played a key role in providing 75 percent of American intelligence on the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

Additionally, MACV-SOG pursued another objective during their missions along the Ho Chi Minh Trail: conducting operations to apprehend prisoners behind enemy lines. These missions were seen as one of the most dangerous tasks and could be either a primary or secondary objective, depending on the circumstances. Nonetheless, such operations received strong support from commanding officers.

Prisoner snatching behind enemy lines

Members of MACV-SOG were incentivized with a reward of $100 for each captured enemy soldier, as well as the promise of rest and relaxation (R&R). Local allies were rewarded with new watches and varying amounts of cash. This incentivization strategy proved effective, leading to several successful captures, such as 12 soldiers in Laos in 1966. These yielded valuable intelligence on enemy troop movements, sizes and base locations.

Capturing prisoners demanded inventive tactics from MACV-SOG operatives. Lynne Black, an operator, meticulously calculated the precise amount of C-4 required to incapacitate a target without causing fatal harm, a process undoubtedly fraught with trial and error. Operatives strategically placed explosives along trails, patiently awaiting the approach of enemy troops before remotely detonating the C-4. This method enabled them to swiftly extract their unconscious targets.

Throughout the Vietnam War, MACV-SOG played a pivotal role in numerous significant engagements, including Operation Steel Tiger, the Tet Offensive, Operation Tiger Hound, Operation Commando Hunt and the Easter Offensive. Despite their skill, their involvement in the conflict remained largely undisclosed until the 1980s.

More from us: Despite Being Up Against 2,000 Enemy Troops, Bernard Fisher Risked His Life to Save a Fellow Airman

It wasn’t until 2001 that the group’s members were formally recognized, with them receiving the Presidential Unit Citation.