Iva D’Aquino’s voyage to Japan

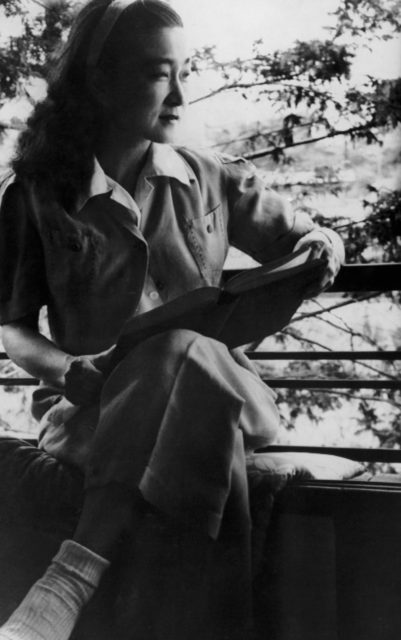

Iva Toguri was born on July 4, 1916, to Japanese immigrant parents, who settled in Los Angeles, California. Throughout her upbringing, Iva’s father emphasized assimilation into American culture, discouraging involvement in Japanese customs. Consequently, young Iva was not allowed to speak Japanese or participating in cultural gatherings, and she ate a blend of Asian and Western cuisines.

In 1941, Iva’s parents sent her to Japan to care for her ailing aunt, who suffered from high blood pressure and diabetes. However, navigating travel to Japan proved challenging amidst strained relations between Japan and the US, leading to suspicion directed towards Japanese-Americans seeking travel documents.

Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor

It wasn’t until November 1941 that Iva decided to return to Los Angeles. However, an issue with her paperwork meant she would miss her California-bound boat scheduled for December 2, 1941. Less than a week later, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and the US declared war.

Iva was immediately approached by the Japanese government, who requested she renounce her American citizenship. When she declined to do so, she was barred from obtaining a war ration card, deemed an “enemy alien” and watched closely. She wanted to be interned with other “enemy aliens,” but was denied due to her gender and Japanese ancestry.

Unable to return home, Iva remained at her aunt’s residence. She soon found herself forced out by neighbors who believed her to be an “American spy.” In need of somewhere to live, Iva relocated to a boardinghouse in Tokyo.

Iva D’Aquino’s beginnings in Japanese radio

Iva obtained a part-time transcribing job with the country’s national news agency, Dōmei Tsūshinsha. It was there she learned of her family’s relocation to an internment camp in Arizona, a fate many Japanese-Americans living on the West Coast faced. She also met her future husband, Portuguese-Japanese pacifist Felipe D’Aquino, while at the station. An act of generosity on his part would lead her to obtain another job, this time at Radio Tokyo.

While with Radio Tokyo (formally known as Nippon Hoso Kyokai), Iva worked as an English-language typist. It was during this time that she began smuggling food to inmates at a local prisoner of war (POW) camp, with her meeting Australian Capt. Charles Cousens and US Army Capt. Wallace Ince.

Cousens and Ince, along with Philippine Lt. Normando “Norman” Reyes, were approached by Japanese government officials to host a propaganda radio show. Titled The Zero Hour, it aimed to lower the morale of troops stationed in the Pacific by reporting on disasters back in the United States.

Initially written by the Japanese, complaints over poor English grammar and syntax eventually allowed the three to gain full control over the content. Due to the language barrier, they were able to fill their broadcasts with sarcasm and double entendres aimed toward the Japanese, without retribution.

Iva D’Aquino becomes “Orphan Ann”

The group swiftly approached Iva, extending an invitation for her to join them. She agreed, under the condition that she wouldn’t be forced to express anything anti-American during broadcasts. Before long, she was on the airwaves using the alias “Orphan Ann,” a nod to the Little Orphan Annie comics and the term coined by Australian soldiers for those isolated from allies: “Orphans of the Pacific.”

During The Zero Hour‘s eighteen-month run, Iva showcased comedic sketches, introduced music, but opted out of participating in newscasts. She affectionately referred to listeners as “honorable boneheads” and refused to travel down the conventional propagandist path.

As time passed, her on-air time dwindled to mere minutes per broadcast, yet her voice resonated across the Pacific. Though the identities of her and other female propagandists remained largely undisclosed, soldiers dubbed them collectively as “Tokyo Rose.” This moniker gained notoriety and posed significant legal hurdles for Iva.

Accusations of treason

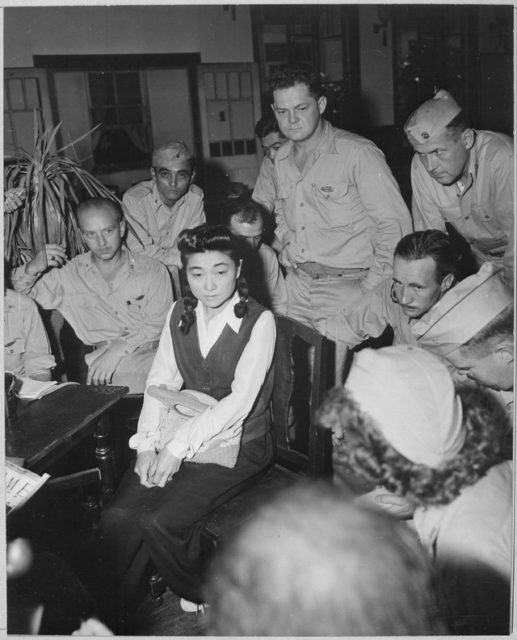

At the end of the Second World War, reporters with Cosmopolitan Magazine and the International News Service put out a $2,000 reward for an interview with the “Tokyo Rose.”

Despite not considering herself “Tokyo Rose,” Iva accepted the offer because she needed money to fund her journey back to the United States. However, upon her arrival in Yokohama on September 5, 1945, she was taken into custody by the US Army, accused of treason for aiding the enemy with her radio broadcasts.

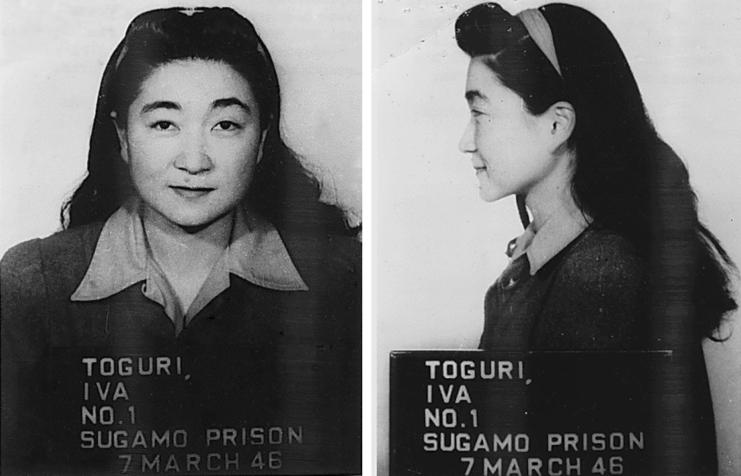

Iva was released a year later after the Army and other counterintelligence agencies found no evidence of treason during her time on Japanese radio. However, post-war America was rife with anti-Japanese sentiment, setting the stage for a difficult return home.

Arrested again on September 25, 1948, Iva faced eight charges of treason. Her trial centered on two key pieces of evidence: testimonies from Japanese witnesses who claimed she spoke negatively about the US on-air, and a supposed phrase – “Orphans of the Pacific, you are really orphans now. How will you get home now that your ships are sunk?” – she’s said to have uttered in October 1944.

Although this quote did not appear in the show’s transcripts, it became the deciding factor in her case. Iva was sentenced to 10 years in prison and fined $10,000. Her US citizenship was also revoked. She served six years and two months at the Federal Reformatory for Women in Alderson, West Virginia, before being granted parole.

Presidential pardon

Iva moved to Chicago to work for her father’s business upon her release, but she couldn’t escape the trouble of being known as the “Tokyo Rose.” The federal government issued a deportation order against her, and she was consistently denied a presidential pardon for her conviction.

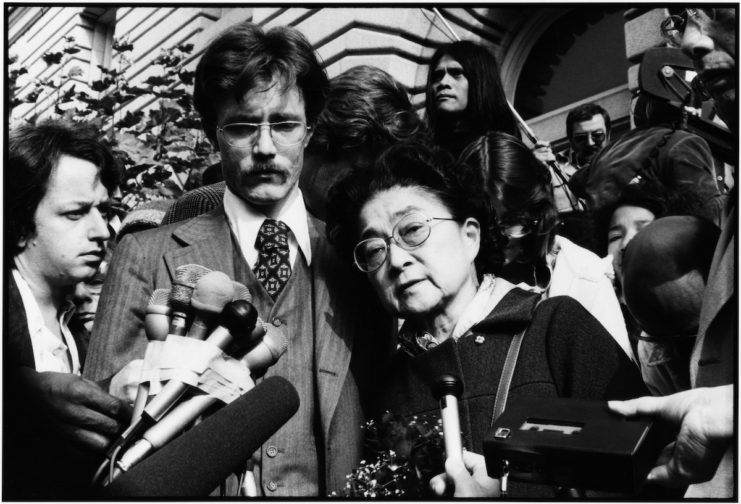

Things turned around in 1976 after two witnesses from the trial claimed they’d been threatened into testifying against Iva. This led the jury foreman to admit the presiding judge had pressured the jury to come back with a guilty verdict.

Journalists and government agencies investigated Iva’s conviction and found numerous other issues, which led advocacy groups to petition again for a presidential pardon. On the last full day of his presidency in 1977, Gerald Ford granted Iva a presidential pardon, nullifying her conviction. The pardon also restored her US citizenship.

More from us: The Bomber Mafia: Success, But At What Cost?

After being pardoned, Iva continued to live in Chicago. She unfortunately had to divorce her husband in 1980, after he was denied entry into the US. She lived a relatively private life and died of natural causes in September 2006.