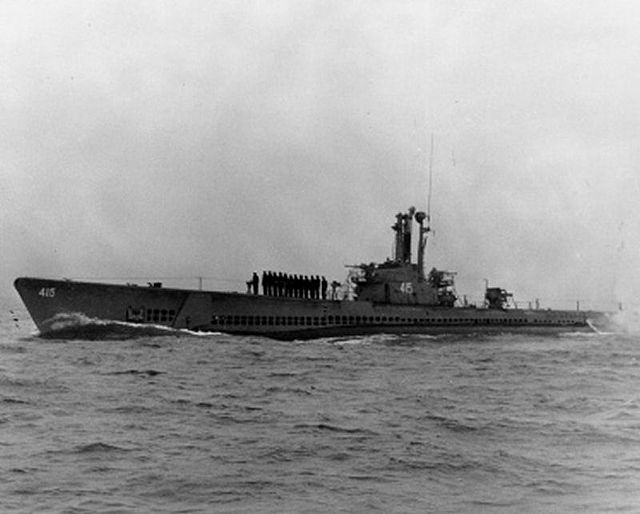

USS Grayback (SS-208)

The USS Grayback began its service on June 30, 1941, under the command of Lt. William A. Saunders. As one of the US Navy’s pioneering fleet submarines, she played a key role in the success of the Allied forces in the Pacific Theater.

Outfitted with four General Motors V16 diesel engines, four high-speed General Electric electric motors, and two 126-cell Sargo batteries, Grayback showcased notable performance, reaching speeds of 20.4 knots on the surface and 8.75 knots submerged. With a range of 11,000 nautical miles at 10 knots, the submarine could stay submerged for 48 hours at a speed of two knots.

To engage enemy vessels, Grayback was armed with a stockpile of 24 torpedoes stored in ten 21-inch torpedo tubes, supported by a Bofors 40 mm and Oerlikon 20 mm cannon. Additionally, a single three-inch deck gun was part of its weaponry. The submarine was manned by a crew of 54 enlisted men and six officers, ensuring smooth and efficient operations.

USS Grayback (SS-208) enters World War II

After the US entered World War II following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the USS Grayback became actively engaged in combat. Initially commissioned into the Atlantic Fleet, she ranked 20th in total tonnage sunk by American submarines, targeting and sinking 14 enemy ships (63,835 tons). Recognized for her exceptional service, Grayback earned eight battle stars throughout the conflict.

In February 1942, Grayback departed from Maine, bound for Hawaii. During her first war patrol along the coasts of Saipan and Guam, she engaged in a four-day standoff with a Japanese submarine. Despite the enemy vessel firing two torpedoes, Grayback managed to escape. A month later, she achieved her first sinking, taking out the Japanese cargo vessel Ishikari Maru.

Experiencing continued success

During later missions, the USS Grayback navigated the South China Sea and St. George’s Passage, confronting challenges like bright moonlight, heavy enemy patrols, and perilous waters. Despite these obstacles, the submarine and her companion ships played an important role in the success of the Guadalcanal Campaign, America’s inaugural major land offensive in the Pacific.

Grayback continued to achieve notable successes, garnering acclaim for rescuing six crewmen who survived the crash of their Martin B-26 Marauder in the Solomon Islands. Despite setbacks during her sixth patrol, her reputation flourished during subsequent missions, including her involvement in one of the first wolfpacks formed by the Submarine Force.

Among all her patrols, Grayback‘s 10th proved the most triumphant — tragically, it also marked the submarine’s final mission.

A successful final mission in the Pacific Theater

On February 24, 1944, the USS Grayback reported sinking two Japanese cargo vessels and damaging two others. The next day, her final transmission confirmed the sinking of the enemy tanker Nanho Maru and damage to the Asama Maru. With only two torpedoes left, the submarine was ordered to return to base in Fremantle, Western Australia.

Grayback was expected to arrive at Midway Island on March 7, 1944, but she never appeared. By March 30, the vessel was officially declared missing, with no survivors.

Captured Japanese records later revealed details of Grayback‘s final moments. On February 27, after attacking convoy Hi-40, the submarine used her remaining two torpedoes to sink the cargo ship Ceylon Maru in the East China Sea. Shortly after, a Nakajima B5N torpedo bomber spotted the vessel and dropped a 500-pound bomb, leading Grayback to “explode and sink immediately” to the seafloor. Anti-submarine aircraft then dropped depth charges on the area to ensure the submarine was fully incapacitated.

Grayback remained undiscovered in this location for nearly a century.

Locating the USS Grayback (SS-208)

During the Second World War, 52 American submarines were lost, taking the lives of 374 officers and 3,131 sailors. The Lost 52 Project is an initiative dedicated to locating all 52 vessels, to bring closure to the families of those who lost their lives. Using state-of-the-art technology, the team captures images and 3D scans of the wrecks they discover to help document each submarine.

On November 10, 2019, the Lost 52 Project announced it had located the USS Grayback some 50 nautical miles south of Okinawa, roughly 1,400 feet below the surface. Her deck gun was found 400 feet away from the main wreckage. The damage the submarine had sustained appeared consistent with what was listed in the Japanese report. There was severe damage aft of the conning tower, and part of the hull had imploded. As well, the bow had broken off at an angle.

A miracle discovery

It’s a miracle they even found the wreck, considering the original coordinates translated by the US Navy were 100 nautical miles off, thanks to a clerical error that was off by just one number.

The team set up a dive team to explore the wreckage, but what they found inside overshadowed the celebratory mood around such an incredible discovery. Tim Taylor, one of the team leads, shared how he felt with The New York Times, “We were elated, but it’s also sobering, because we just found 80 men.”

Prayers of family members have finally been answered

Raymond Parks, the uncle of Gloria Hurney, held the position of electrician’s mate, first class, and was among the sailors who went missing on the USS Grayback. Hurney, alongside others, had resigned themselves to the notion that they might never find the wreckage. Nevertheless, the Lost 52 Project disproved their expectations.

Are you a fan of all things ships and submarines? If so, subscribe to our Daily Warships newsletter!

Although the discovery carried a mix of emotions, it ultimately provided solace and tranquility to the families who had patiently awaited seventy-five years to uncover the final resting place of their beloved ones beneath the ocean’s surface.