The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) is widely acclaimed as a cinematic masterpiece and has won many Academy Awards. However, it is important to acknowledge that the film does include fictionalized elements into its narrative, particularly concerning the central character, Lt. Col. Nicholson.

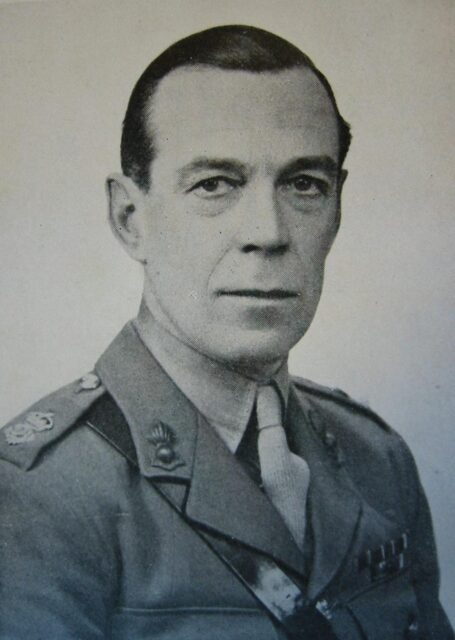

While inspired by the real-life figure Lt. Col. Philip Toosey, the movie takes liberties with his portrayal within the prisoner of war camp, portraying him in a manner that deviates from historical accuracy and paints him in a negative light, which is different from reality. Toosey’s actual conduct earned him multiple awards and deep respect from his fellow prisoners.

Philip Toosey’s father wouldn’t let him attend Cambridge

Philip Toosey was born in Oxton, Birkenhead, where he was raised as the eldest of seven siblings. His father, Charles, captained a successful shipping agency, and his mother, Caroline, was the daughter of the warden of Dublin Gaol.

Until the age of nine, Philip received his education under the guidance of his parents. He then transitioned to formal schooling, where his academic abilities shone. His excellence earned him a scholarship to Cambridge. However, despite his intellectual promise, his father had reservations about scholarly pursuits and prevented him from accepting the scholarship. Instead, Toosey began an apprenticeship under his Uncle Philip, a prominent figure in Liverpool’s cotton merchants community.

Toosey was part of the evacuation of Dunkirk

In 1927, Toosey joined the 59th (4th West Lancs) Medium Brigade, Royal Artillery of the Territorial Army under the leadership of Lt. Col. Alan C. Tod. His association with Tod proved beneficial in 1929 when his uncle’s business collapsed, prompting Toosey to join Baring Brothers merchant bankers, where he assisted his commanding officer.

Toosey advanced in the Territorial Army, achieving the rank of lieutenant by November 1931, and securing further promotions before World War II. In 1940, the 59th Brigade was deployed to Belgium but soon participated in the evacuation of Dunkirk.

Returning to the UK, Toosey was promoted to lieutenant colonel and entrusted with command of the Royal Artillery’s 135th (Hertfordshire Yeomanry) Field Regiment.

Philip Toosey refused to leave his men behind in Singapore

In 1941, Philip Toosey and his men were sent to Singapore and participated in one of the worst military defeats in British history. Given his reputable leadership, he was ordered to return to Britain with the evacuation that occurred in February 1942. However, he refused the order and stayed with his men, joining them in their captivity at the Tamarkan prisoner of war (POW) camp.

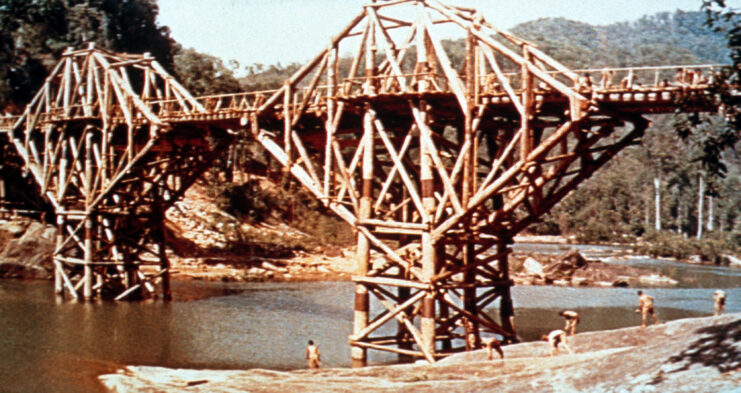

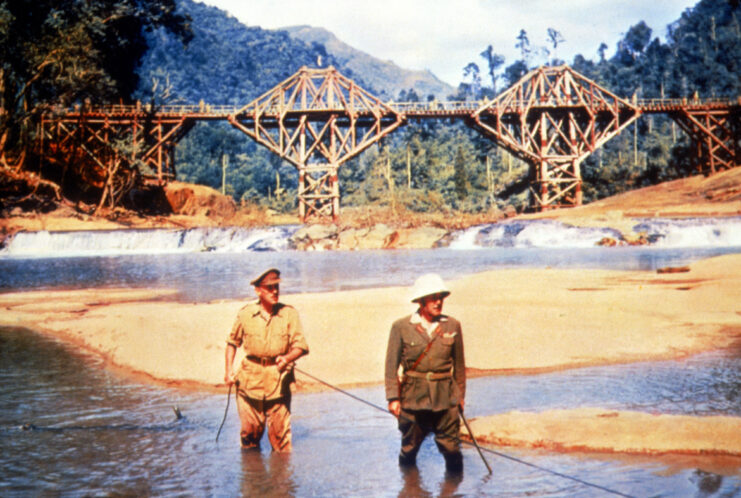

The POW camp was part of a project that sought to build several railroad bridges over the Khwae Noi; they were intended to link Thai and Burmese rail lines, to establish a more direct route between Bangkok and Rangoon, to support the Japanese occupation of Burma.

Building the bridges was no small task, and it proved to be extremely dangerous. About 100,000 conscripted Asian laborers and 12,000 POWs died working on the project, earning it the nickname, the “Death Railway.”

Attempts to sabotage construction

While imprisoned, Philip Toosey used his leadership skills to save the lives of as many of the 2,000 Allied prisoners at the camp. He organized a food and medicine smuggling operation with a Thai merchant, and disciplined the POWs to maintain cleanliness and hygiene. He insisted on a policy of unity and equality, breaking down the rank system by refusing to allow separate officers’ messes or accommodations. For his efforts, he earned the utmost respect from his men.

Along with his leadership, Toosey also tried to delay and sabotage the construction of the bridges. Collecting termites, he set them on the wooden structures, and would put things into the concrete mixtures, to prevent proper mixing. He also organized escapes from the camp, concealing disappearances and taking a beating once get aways were realized.

Toosey is granted more autonomy by the Japanese

Unfortunately, Toosey’s efforts weren’t enough to prevent the completion of the bridges. The wooden and concrete bridges were finished in 1943, as was a third made from steel. Toward the end of the war, the wood and concrete bridges were both destroyed, and, in June 1945, the steel structure was bombed, but survived.

The Japanese considered Tamarkan to be the best-run POW camp, all thanks to Toosey. As such, they granted him quite a bit of autonomy. He was later transferred to an Allied officers’ camp, where he became a liaison officer with the Japanese.

Philip Toosey saved Sgt. Maj. Saito’s life

Before the conflict, Philip Toosey weighed around 175 pounds. However, after being held captive in a prisoner-of-war camp, his weight drastically dropped to just 105 pounds, a startling transformation. True to his character, when he was freed, he chose not to return home immediately. Instead, he embarked on a 300-mile journey to help liberate his fellow prisoners, despite his weakened state.

During the Japanese war crimes trials, Toosey played a crucial role in saving Sgt. Maj. Saito, the second-in-command at Tamarkan. Saito was considered the most reasonable officer among the POWs.

Due to his softer treatment, Toosey spoke on Saito’s behalf, sparing him from facing trial and possible death or imprisonment. This advocacy created a deep mutual respect between the two men, and they continued to correspond after the war.

Controversy over The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957)

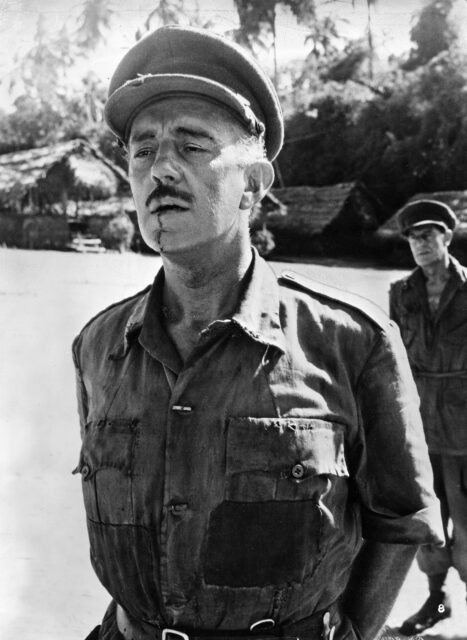

The events that occurred in Singapore and at the prisoner of war camp served as the inspiration for Pierre Boulle’s 1952 novel, The Bridge Over the River Kwai. The book was turned into an Oscar-winning film, The Bridge on the River Kwai, in which Alec Guinness plays Lt. Col. Nicholson, inspired by Toosey.

Unfortunately, the film and the novel took creative licensing with the real events, turning Toosey into someone who collaborated with the Japanese. This caused outrage among the former POWs who knew of his true involvement. When the film was released in 1957, many veterans pushed for him to speak out against the incorrect portrayal.

Toosey wrote a letter to the Daily Telegraph

At first, Toosey refused to do so, but he was later convinced to write a letter to the Daily Telegraph, encouraging other veterans to identify the injustice of the film. However, it was The Bridge on the River Kwai‘s shaping of public perception that caused him to really do something about it. He agreed to an interview with Peter Davies, conducted over the course of several years. The only stipulation was that it couldn’t be published until after his death.

After retiring from the Territorial Army in 1954, Toosey was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire and continued working with veterans. He died on December 22, 1975.

More from us: Harry Belafonte Narrowly Missed One of WWII’s Deadliest Disasters On US Soil

From the over 48 hours of footage Davies collected, he compiled a book, titled The Man Behind the Bridge, and put together a BBC Timewatch program documenting Toosey’s achievements in the war. The former soldier’s granddaughter, Julie Summers, also wrote a book outlining the true events that occurred in Thailand, titled The Colonel of Tamarkan.