Throughout the Second World War, Allied and Axis militaries struggled with desertion. Among the American forces alone, most occurred in the European Theater – an estimated 50,000. Sentences for such a crime varied, with 49 men sentenced to execution. Of that total, 48 had their sentences commuted. That left only Pvt. Eddie Slovik as the sole US soldier to be executed for desertion during the conflict.

Eddie Slovik joins the war effort

Born in Detroit, Michigan in 1920, Eddie Slovik earned quite the rap sheet at a young age. He was first arrested when he was only 12 years old, and committed numerous crimes in the following years, including disturbing the peace, break and enter, and petty theft.

Slovik served nearly a year in prison, beginning in October 1937, before he was paroled. This didn’t last long, however, as he stole a car while drunk and crashed it, which sent him back to prison. He was paroled, again, in April 1942, and went on to obtain a job in plumbing and heating.

Although World War II was well underway by this point, Slovik wasn’t eligible to enlist, as he was considered a criminal and, therefore, deemed “morally unfit for duty.” A year after marrying his wife, this classification system was changed, and he was drafted into the US Army on January 3, 1944.

After completing basic training Stateside, Slovik was sent overseas with the 3rd Replacement Depot.

Deserting his post

Eddie Slovik was transferred to the 28th Infantry Division, despite his vocal hatred of guns, and assigned to Company G, 109th Infantry Regiment.

While traveling near Elbeuf, France, he and Pvt. John Tankey were forced to take cover during an artillery attack, causing them to become separated from their comrades. The pair were left behind, and subsequently took up with a Canadian military police unit for six weeks, cooking, driving trucks and guarding enemy prisoners of war (POWs). Eventually, Slovik’s company was informed of his and Tankey’s whereabouts and arranged for them to rejoin their comrades on October 7, 1944.

Clearly, the artillery attack had a profound effect on Slovik, who informed Capt. Ralph Grotte that he was too scared to serve on the frontline, and asked, instead, to be transferred. He was very clear that, should he be assigned to the rifle platoon on the front, he would run away, to which the captain clearly responded that such actions would be considered desertion.

Grotte refused to reassign Slovik, and, as promised, the private deserted his post the following day. Tankey attempted to stop him, but was unsuccessful.

Eddie Slovik is taken into custody

Unlike many deserters, Eddie Slovik made no attempts to hide his actions, in the moment or afterward. In fact, when he left his company, he approached a cook at a military government detachment of the 112th Infantry Regiment and presented him with a handwritten note. In it, he confessed what he’d done and said he would do it again if forced to return to the front. The cook turned him over to military police, who, in turn, took him to his company commander.

Instead of immediately taking Slovik into custody, the commander urged him to destroy the note, but the private refused. He was given a second opportunity to do so by Lt. Col. Ross Henbest, who said he could return to service without charge. Unsurprisingly, Slovik, again, refused.

With no other option, Slovik was taken into custody and asked to write a secondary statement, indicating that he knew his first note would incriminate him.

Eddie Slovik is court-martialed

Eddie Slovik appeared in front of divisional judge advocate Lt. Col. Henry Sommer, who also offered him the chance to rejoin his unit. Sommer also presented him with the option to move to an entirely different infantry regiment, with the understanding that the reason for the transfer not be disclosed. Slovik was skeptical, and said, “I’ve made up my mind. I’ll take my court martial.”

As expected, he was charged with desertion to avoid hazardous duty and court-martialed on November 11, 1944. During the trial, many servicemen were called forward to attest that Slovik had intended to run away. To make matters worse, he refused to testify and defend himself.

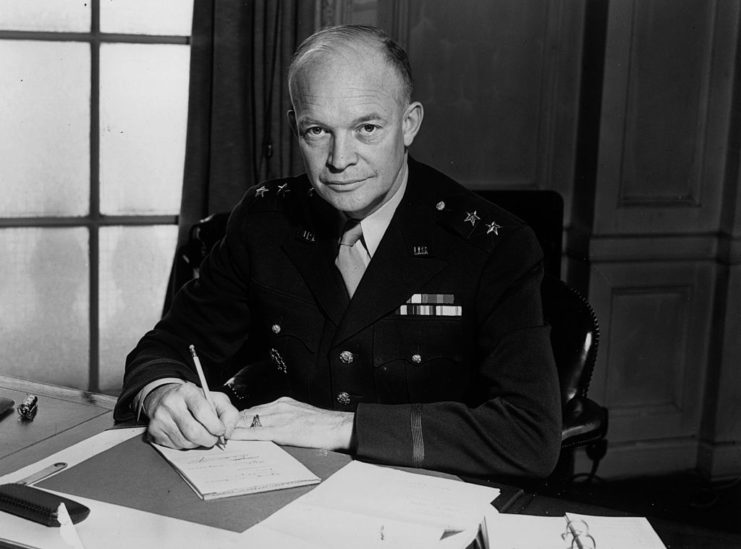

When the trial concluded, Slovik was sentenced to death. He was shocked by the verdict, as he’d been expecting to receive 20 years of hard labor. As a last ditch effort to save himself, he reached out to Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, in the hope he would commute the sentence. The Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force refused, noting that the US Army needed to discourage further desertions.

Execution at the hands of the US Army

At only 24 years old, Eddie Slovik was executed by firing squad at 10:04 AM on January 31, 1945. It’s believed his last words were to Father Carl Patrick Cummings, who was in attendance. Shortly before the execution, the chaplain said to him, “Eddie, when you get up there, say a little prayer for me,” to which Slovik responded, “Okay, Father. I’ll pray that you don’t follow me too soon.”

It’s believed Slovik was executed, rather than his sentence commuted, for a number of reasons. Some have pointed out that it was a matter of being in the wrong place, at the wrong time. The US Army was experiencing a higher than normal level of desertion, so wanted to make a statement.

According to Slovik himself, “They’re not shooting me for deserting the United States Army, thousands of guys have done that. They just need to make an example out of somebody and I’m it because I’m an ex-con. I used to steal things when I was a kid, and that’s what they are shooting me for. They’re shooting me for the bread and chewing gum I stole when I was 12 years old.”

The Execution of Private Slovik (1974)

The death of Eddie Slovik was depicted in William Bradford Huie’s 1954 book, The Execution of Private Slovik, as well as the 1974 movie of the same name.

Huie’s work came together after he was shown a European graveyard that contained the remains of unidentified US soldiers. He set to work investigating the site and identified Slovik as one of the bodies. Although Eisenhower made an effort to stop the book from being published, the then-US president was unsuccessful.

More from us: Frederic Walker: The Most Successful Anti-Submarine Commander During the Battle of the Atlantic

Interestingly, it was Frank Sinatra who first acquired the rights to turn the book into a film. There was significant public backlash to this, with many accusing the musician of being a Communist sympathizer. Ultimately, he sold the rights to filmmaker Richard Dubelman, who produced it and cast Martin Sheen in the lead role.

Overall, the movie was well-received and, for the most part, historically accurate, as the film crew referenced Slovik’s declassified military records when outlining the series of events.