During the Battle of the Bulge, Operation Bodenplatte was developed to cripple the Allied forces’ airfields in the Low Countries. While Wehrmacht troops engaged in a ground offensive in the Ardennes, the Luftwaffe was tasked with incapacitating as many Allied aircraft as possible. Unfortunately for the Germans, this operation, often dubbed the “Hangover Raid,” ultimately dealt a considerable blow to the remnants of their own air force.

Planning the Luftwaffe‘s last grandstand in the air

Following Allied advancements in France after D-Day in June 1944, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower adeptly capitalized on logistical challenges and unfavorable weather conditions to drive his forces deeper into the Germans’ heavily fortified defensive positions. The German military, including the Luftwaffe, grappled with a range of obstacles, from fuel scarcities to a lack of seasoned pilots.

Seeking to regain air superiority, Germany planned to strike Allied airfields and aircraft, to disrupt their operations across the Western Front. On September 16, 1944, Generalleutnant Werner Kreipe, head of the Luftwaffe‘s General Staff, was tasked with orchestrating such an offensive.

The plan, devised by General of Fighters Adolf Galland and endorsed by the Luftwaffe‘s commander-in-chief, detailed assaults on airfields in France, Belgium and the Netherlands, in support of the Ardennes Offensive. This strategy underwent refinement by Generalmajor Dietrich Peltz, who advocated for a unified, synchronized strike to maximize impact by preventing engagements between skilled Allied aviators and their less-seasoned German counterparts.

Several units were temporarily redeployed from duty on the Western Front to participate in what became known as Operation Bodenplatte. The primary aircraft flown were Messerschmitt Bf 109s and Focke-Wulf Fw 190s. Medium bombers and night-fighter units served as pathfinders.

Initially slated to coincide with the onset of the Battle of the Bulge, the aerial assault encountered multiple delays over subsequent weeks due to adverse weather conditions. With improved weather, the decision was made to launch the operation on New Year’s Day 1945, in conjunction with Operation Nordwind.

Operation Bodenplatte

Rather than ushering in the new year with celebrations on the evening of December 31, 1944, the Luftwaffe pilots involved in Operation Bodenplatte were directed to retire early, while ground crews diligently prepared their aircraft. In the early hours of January 1, 1945, they took off from their bases, targeting 17 airfields: Ursel, Deurne, Woensdrecht, Asch, Evere, Volkel, Grimbergen, Sint-Truiden, Ghent, Metz, Melsbroek, Ophoven, Eindhoven, Heesch, Le Culot, Gilze en Rijen and Maldegem.

A subsequent examination of the plans revealed that several targets were mistakenly attacked.

Maintaining radio silence and guided by flares from Junkers Ju-88 and -188s, the plan was to execute the strike at dawn, at roughly 9:20 AM local time. The Germans capitalized on the element of surprise, catching the Allied airfields off guard as they were unprepared for an aerial assault; despite British Intelligence noting increased Luftwaffe movement and a buildup in the region, the imminent attack had gone unnoticed.

Upon reaching the airfields across the Low Countries, it became evident that numerous Royal Air Force (RAF) squadrons were on missions or absent altogether. Grimbergen, for instance, greeted Jagdgeschwader 26 (JG.26) with an empty airfield, as the 132 Wing RAF had recently relocated to Woensdrecht. The remaining aircraft were defended by flak crews, resulting in more aircraft losses for the Luftwaffe than the Allies suffered on the ground.

Similarly, in Ghent, home to the No 131 (Polish) Wing, several Mk IX Supermarine Spitfire squadrons were away on an aerial bombing mission. Consequently, German pilots could only target buildings, trucks and a limited number of parked aircraft.

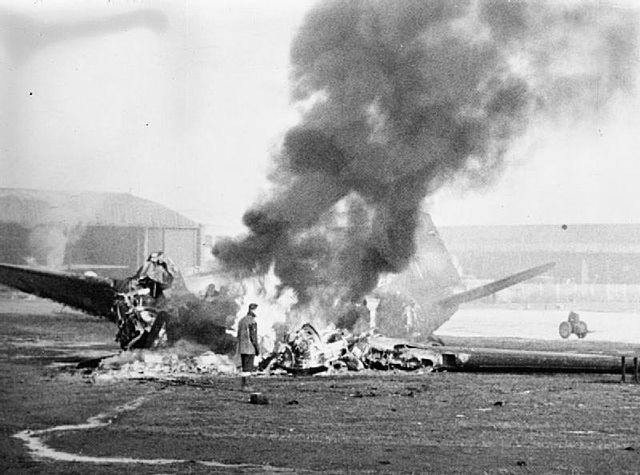

Among the heavily damaged airfields was Metz, where the American 365th Fighter Group’s fleet of Republic P-47 Thunderbolts faced strafing with machine gun and cannon fire, causing not only damage to aircraft, but also triggering explosions of fuel tanks and munitions.

Despite facing a resilient Allied defense, the Luftwaffe inflicted casualties, both in terms of human and aircraft losses. By around 12:00 PM that day, the German pilots gradually departed in ones and twos. An assessment of the inflicted damage revealed varying degrees of impact, with some targets suffering considerable damage while others escaped relatively unscathed.

The Allies suffered far less damage than the Germans

Although the Luftwaffe asserted that Operation Bodenplatte achieved success in surprising the Allies, strategically, it severely hampered what little remained of Germany’s faltering air forces. Of the 850 aircraft involved, 40 percent were destroyed or damaged. As for the pilots flying them, 143 were killed or listed as missing in action (MIA), 70 were taken as prisoners of war (POWs) and 21 suffered various injuries. This marked the Luftwaffe‘s most significant single-day loss.

Approximately half of the German aircraft downed during Operation Bodenplatte were reportedly lost to friendly fire. A post-mission analysis revealed that only a third of the air combat groups involved – 11 out of 34 – had executed their attacks on time and with surprise.

In contrast, the Allies quickly recovered from the air raids. Only 250 aircraft were destroyed and 150 were damaged and repaired. Furthermore, only a few pilots lost their lives. Within a week of Operation Bodenplatte, many aircraft had already returned to the air and were participating in the ongoing Battle of the Bulge in the Ardennes.

Why did Operation Bodenplatte go so wrong?

An examination of Operation Bodenplatte revealed the mission was destined to fail from the outset. The majority of the aviators involved lacked experience and had undergone significantly less training than their counterparts who’d flown earlier in the war. This lack of expertise manifested in their conduct during the attack, as they circled back over the airfields multiple times, giving the Allies on the ground additional opportunities to fire anti-aircraft artillery.

Inadequacies in planning also played a significant role in the mission’s downfall. Several flight paths directed pilots over heavily guarded and armed V2 launch sites, particularly around The Hague. Moreover, the maps provided by the higher command were incomplete, featuring only illustrations of the intended targets while omitting crucial details about the flight paths. This omission aimed to prevent the Allies from deciphering critical information if the documents fell into their hands.

Secrecy further contributed to the mission’s shortcomings. Most commanders were prohibited from providing advanced notice to pilots, resulting in many receiving instructions moments before taking off. This lack of detailed information led to them taking to the air without a comprehensive understanding of their mission. As far as they knew, they were participating in a reconnaissance operation.

More from us: Operation Chariot: The Daring British Raid on St. Nazaire

Ultimately, the Allies didn’t exhibit the hangover-induced vulnerability that the Luftwaffe had anticipated after their New Year’s Eve celebrations. Numerous Allied personnel had moderated their revelry the night before, aware of scheduled missions for the following day. In fact, some were en route back to base when the German attack unfolded. This fortuitous timing enabled them to offer supplementary air support, successfully eliminating several enemy aircraft.