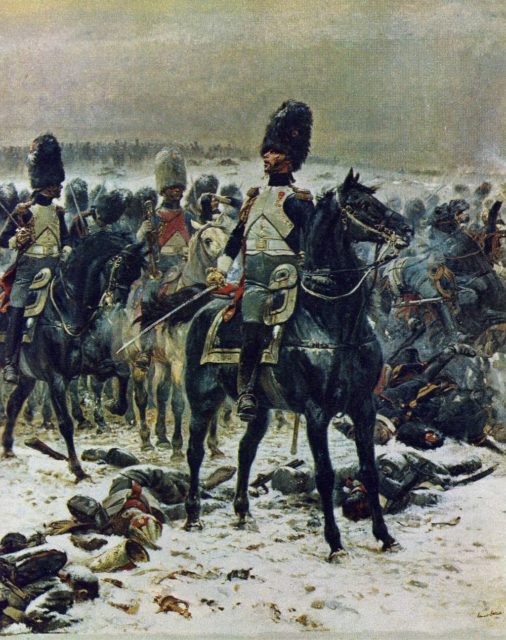

The Imperial Guard were the most famous soldiers in Napoleon Bonaparte’s army. An elite core of fighting men, they held a special place in the Emperor’s heart and served a unique function in asserting his power.

Not Always the Imperial Guard

The force that became the Imperial Guard started out as the Consular Guard in 1799 while Napoleon was First Consul. At that time, he was effectively ruler of France, although the nation was officially still a republic.

In May 1804, Napoleon became Emperor of the French. The Garde des Consuls was retitled the Garde Impériale, and the famed Imperial Guard was born.

The Imperial Guard Included Troops of all Arms

The classic image of the Imperial Guard, shaped by their actions at Waterloo, is ranks of proud and disciplined infantry. In reality, the Imperial Guard included troops from every branch of the military. There were infantrymen, cavalry, and artillery. The invasion of Spain involved Imperial Guard seamen lost in combat at Bailen.

Not All of the Imperial Guards were French

The Imperial Guard had a reputation as France’s finest fighting men, but not all of them were French. Like the rest of Napoleon’s army, they expanded and diversified with his Empire. They incorporated elite units from elsewhere in conquered or allied Europe. By the time of the invasion of Russia in 1812, the Imperial Guard included brigades of Hessian and Portuguese cavalry.

The Imperial Guard had Strict Entry Requirements

As an elite fighting force, the Imperial Guard set clear standards for entry. Candidates had to be at least 5ft 6in (1.78 meters) tall which was rarer at that time than now. They had to prove their worth as soldiers by fighting in at least three campaigns or being wounded in combat twice. They needed to be able to read and write; these were smart men, not merely fighters.

The Imperial Guard Enjoyed Special Privileges

In return for meeting these strict requirements, soldiers in the Imperial Guard received privileges far beyond those of ordinary soldiers. Their pay was greater; their rations were better, and the quarters in which they were housed were superior to those of their comrades. When supplies ran low on a campaign, what provisions remained were reserved for the Imperial Guard; to keep the best troops ready for battle.

Being an Imperial Guard Meant Carrying Extra Baggage

An ordinary French infantryman marched beneath the burden of a 58-pound pack. The Imperial Guard infantry, with their extra ceremonial equipment, brought the weight up to 65 pounds. The packs included food for a week, spare clothes, and 60 rounds of ammunition for their muskets.

The Imperial Guard had to be Careful Around Women

To ensure the chivalrous and upstanding reputation of the Imperial Guard, members had to follow strict rules in their conduct around women. They were not allowed to frequent places of ill repute, depriving them of one of the most common pleasures of off-duty soldiers. Around “proper” ladies, they also had to take care. Although they could escort a lady, she was not allowed to be seen taking a soldier’s arm.

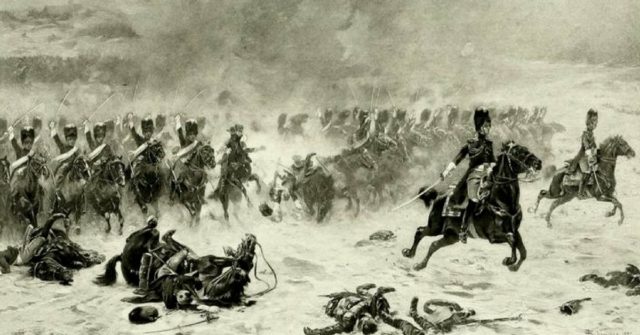

The Imperial Guard were Almost Wiped Out in Russia

The 1812 invasion of Russia, which was so disastrous for the Napoleonic army as a whole, nearly wiped out the Imperial Guard. Between the severe weather, supply shortages, and in combat against the Russians, the army took a savage beating. Rather than being protected by their elite status, the Imperial Guard at times bore the brunt of the losses. By the end of the campaign, their forces had been reduced from over 50,000 soldiers to a mere 1,500.

Napoleon Kept Expanding the Imperial Guard

Despite its setbacks and sometimes horrifying casualties, the Imperial Guard grew throughout Napoleon’s reign. At first, it remained what it had initially been set up as – an expanded personal bodyguard, consisting of 5,000 infantry, 2,000 troopers, and 24 guns. However, by January 1810, existing Imperial Guard forces in Spain were reinforced with a further 17,300 men. By the time of the Russian campaign, Guard numbers had swelled to 56,000. As Napoleon’s reign approached its end in 1814, 112,000 soldiers served in the Imperial Guard.

The Imperial Guard Served a Political Purpose

As befitting the elite troops of an Emperor, the Imperial Guard had a political function as well as a military one.

Napoleon put a lot of trust in his marshals. They gained a lot of status both within the army and with the wider public, as they were held up as examples of leadership and heroism. However, as the former marshal Bernadotte showed when he took over Sweden and then allied with Russia, these men had ambitions of their own.

In keeping a strong personal force, whose privileges were based in service to their Emperor, Napoleon provided himself with security against political maneuvering by his marshals. The very best of men were in the Imperial Guard, and their existence would be enough to deter any thoughts of a coup.

The Imperial Guard Often Acted as Battlefield Reserves

Their political function may have been one of the reasons why Napoleon so often held the Imperial Guard back in a battle, not committing them and risking casualties. It also served another purpose in allowing him to bring in a hard-hitting force at a critical juncture, usually turning the tide of combat.

It also preserved the mystique of the Guard. If they seldom fought, there was less chance of them being defeated, and so they could maintain their reputation as Europe’s elite.

The Imperial Guard Only Failed Napoleon at Waterloo

The only time the Guard failed Napoleon was at the moment of his final undoing – the Battle of Waterloo (1815). He held them back throughout most of the battle, in case he needed them to fight the Prussians. Eventually, with his reserves whittled away, he ordered the Guard to advance against the British lines.

However, he left it too late. The British had time to recover from previous attacks. For the first time, the Imperial Guard retreated and put a nail in the coffin of French morale.

Sources:

Alan Forrest (2011), Napoleon.

Robert Harvey (2006), The War of Wars: The Epic Struggle Between Britain and France: 1789-1815.

Philip Haythornthwaite (2004), The Peninsular War: The Complete Companion to the Iberian Campaigns 1807-14.

Alistair Horne (1996), How Far From Austerlitz? Napoleon 1805-1815.