One of the most powerful tools in Napoleon Bonaparte’s intellectual arsenal was the connections he drew between his own life and that of great figures from history.

This provided the French ruler with inspiration, and more importantly fulfilled an ideological purpose. By linking himself to these great men, in an age when history was seen as shaped by them, he could improve his public image, win support and provide legitimacy for his regime.

For a French ruler, no example could be more important or more appropriate than Charlemagne.

Frankish King and Holy Roman Emperor

The King of the Franks from 768 to 814 AD, Charles the Great, or Charlemagne, was one of the most influential figures in early medieval history. During his 46 year reign, he conquered most of western Europe, becoming King of the Lombards and Holy Roman Emperor – the first leader to bear the title of Roman Emperor since the fall of the Roman Empire in the west three centuries before.

With its elite cavalry troops, effective law making and inspirational cultural renaissance, Charlemagne’s Carolingian Empire would provide an inspiration for the rulers who followed. He laid the foundations for the later nations of France and Germany. In France in particular, he came to be seen as a founding national hero, a figure akin to King Alfred or the legendary Arthur in Britain.

His image was, therefore, a powerful one for Napoleon to associate with, an important example of a French ruler with Europe-wide ambitions.

Outside Encouragement

Already a fan of the Frankish king, Napoleon was encouraged in his attempts to imitate Charlemagne by others around him.

Prior to his falling out with Pope Pius VII, Napoleon was encouraged by the papacy to follow the example of Charlemagne. After all, the Frankish king had supported and protect the church during an era of chaos and violence.

Even some within what remained of the Holy Roman Empire saw Napoleon as a possible ruler for the contemporary institution that had evolved from Charlemagne’s empire. The Archbishop of Mainz and Arch-Chancellor of the Holy Roman Empire, Karl Theodor Anton Maria von Dalberg, suggest in 1806 that the best hope for preserving the Empire – which by this pointed was famously neither holy, not Roman, nor an empire – was to give the crown once held by Charlemagne to Napoleon.

With both his own interests and the influence of others encouraging him to imitate Charlemagne, Napoleon sought in several ways to make himself seem like the new version of the ancient king.

French Coronation

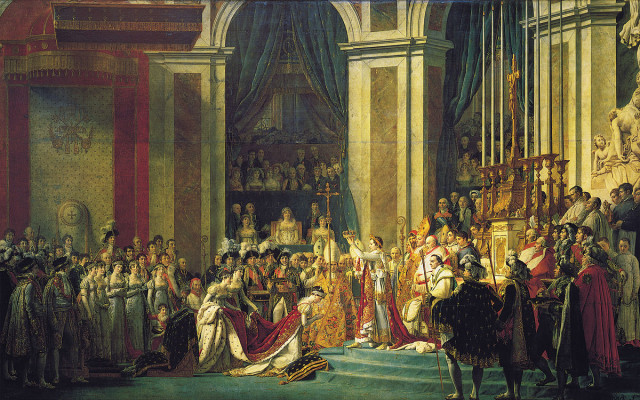

The most famous incident in which Napoleon associated himself with Charlemagne was his coronation in Notre-Dame de Paris on 2 December 1804. This was the moment at which France returned from being a republic, as it had been since the revolution, to being a monarchy. Though Napoleon had effectively ruled for several years, he now took a royal title. Like Charlemagne, he was founding a French dynastic line.

Though this was a return to the monarchy for France, it was a monarchy with a symbolically important difference. At its head was an emperor, not a king. In this way, Napoleon associated himself less strongly with the example of the overthrown royal line, against which many in France still harboured deep resentments. Instead, he had taken the title last worn in France by Charlemagne.

Just as symbolically, he gave a key role in his coronation to the Pope. Napoleon, unlike Charlemagne, crowned himself with his own hands. But like Charlemagne, he ensured that his imperial coronation carried the blessing of the head of the Catholic church.

Lombard Coronation

The coronation in Paris was not the only one Napoleon received. At Milan on 26 May 1805, he had himself crowned King of Italy. On this occasion, he was crowned with the Iron Crown of Lombardy, one of the most ancient royal relics in Europe, with a heritage and mythology stretching back to Charlemagne’s Kingdom of Lombardy.

Once again, Napoleon was taking on a title associated with Charlemagne. This time, he did so wearing a crown that many believed Charlemagne himself had worn. To hammer the point home, he marked the occasion by giving a painting of Charlemagne to the city of Milan.

Universal Monarchy

The Austrian noble Colloredo wrote of Napoleon that he “sought to become a new Charlemagne and aspired to ‘universal Monarchy’”. What Colloredo uttered as a warning, Napoleon and his associates, such as his brother Lucien, saw as a fine example of the potential for unity across the continent.

Like Charlemagne, Napoleon sought to unite all the lands he could reach, to create a single monarchy governing the nations of Europe. The dream was not to make all nations the same but to unite them under one law and one set of political values. It was an aspiration that linked Napoleon’s early endeavours in the cause of the republic with his later wars of imperial conquest.

Associations with the Great Name

Napoleon worked tirelessly to push the name of Charlemagne into the forefront of people’s minds when they saw him. He regularly spoke about the medieval emperor, telling papal representatives in 1809 that “In me you see Charlemagne. I am Charlemagne, me!” Some connections were little more subtle, though not much, as when he travelled aboard the boat Charlemagne in 1811.

He encouraged Jacques-Louis David, who famously painted propaganda pieces for the emperor’s reign, to connect him with Charlemagne. That name appears, along with others, in the rocks beneath Napoleon in David’s portrait of him crossing the Alps.

Aachen

Even Charlemagne’s capital of Aachen was incorporated into this grand work of propaganda. A portrait of the new emperor was displayed there, and in 1811 an effigy of Charlemagne was paraded through the city, with a message inscribed upon it in both German and French: “I am only surpassed by Napoleon.”