Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt was one of the strangest failures in military history. A young general and statesman at the height of his abilities he made a miscalculation that cost his armies dearly.

Yet he turned this defeat into a political triumph. Fresh from the Egyptian campaign he and his fellow Consuls took control of the French Republic.

What happened in Egypt?

The Lure of the East

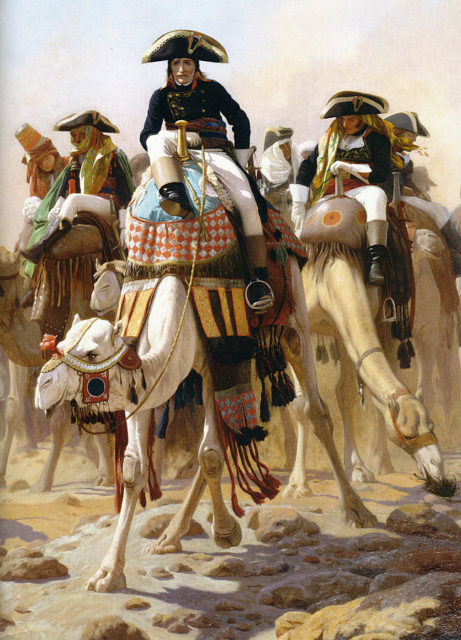

Napoleon had several reasons for invading Egypt. Culturally, there was the long-standing European dream of experiencing the exotic east. This was coupled with an interest in the Enlightenment which drove a fascination with Egypt.

Politically, he wanted a great success to cement his status in France and isolate enemies abroad.

Militarily, he wanted to undermine the British by cutting off their important trade routes. He hoped to undermine their military strength without facing the fearsome challenge of invading Britain.

A Triumphant Start

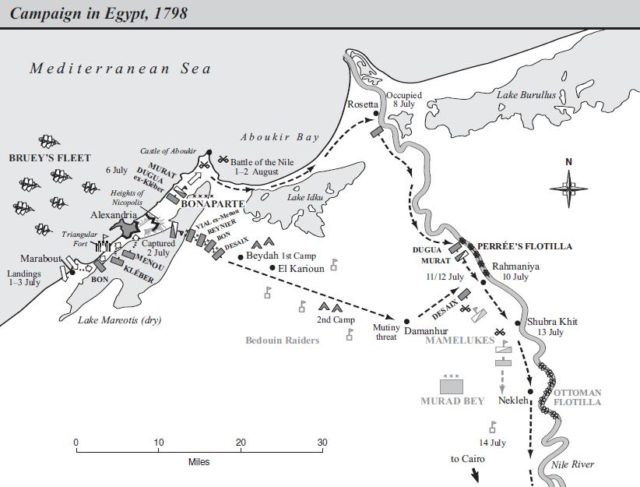

On the way to Egypt, Napoleon secured his supply route across the Mediterranean, as well as French outposts in the eastern part of that sea. The fortress City of Valletta was taken from the Knights of St John through a combination of bribery and intimidation. Malta became a strategically important French outpost.

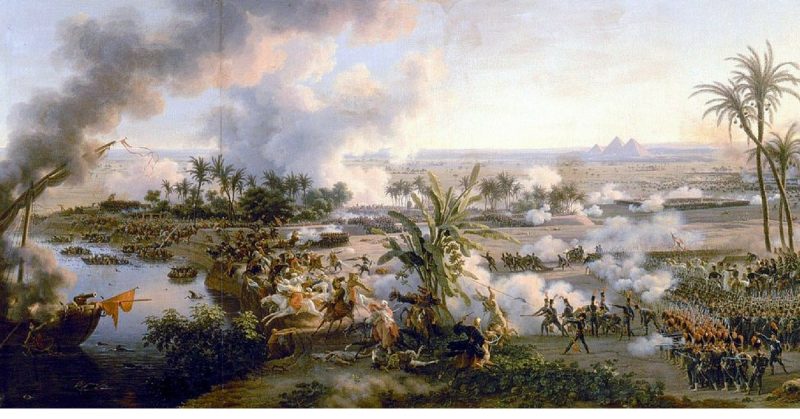

Reaching North Africa, the French faced the sort of army that filled their oriental dreams. It was a force of Mamelukes, dressed in clothes that seemed exotic to the French soldiers, wielding curved scimitars, and fighting in a disorganized fashion. This encounter reinforced French images of the spectacular but barbaric east. It also reinforced their sense of superiority over the Egyptians.

Against the Egyptians and Turks, Napoleon won a series of impressive victories at the Pyramids, Mount Tabor, and Aboukir. The Battle of the Pyramids is especially noteworthy not just for its impressive setting but also the result. The French lost 300 soldiers. The Mamelukes 2,500 men.

British Intervention

However, disaster was looming.

At the start of August 1798 the British fleet under Admiral Horatio Nelson finally tracked down the French fleet at the mouth of the Nile. Rather than wait to fight in daylight as was conventional, Nelson attacked at the end of the day, surprising the French. Daring tactics allowed him to concentrate the firepower of his fleet, wreaking havoc.

It was one of the most destructive battles in naval history, and one of Nelson’s greatest successes. The French fleet was devastated. The jewel in its crown, the 120-gun flagship L’Orient, was destroyed when her powder stores exploded, killing 1,000 crewmen. She had been carrying the wealth meant to finance Napoleon’s campaign, which sank without trace.

With their fleet gone and the British controlling the Mediterranean, the French were now cut off in Egypt. There was no hope of supplies, reinforcements, or retreat.

Advancing to Retreat

At first, Napoleon acted as if the Battle of the Nile did not matter. He continued his attempts to turn Egypt into a French colony. As it became evident the tactical situation had changed, he turned his attention north and east, heading into Syria to fight the Turks.

There he was thwarted again, this time on land. An attempt to capture the City of Acre was unsuccessful due to a combination of disease and the British. Plague swept through the French Army, and the British Navy defeated the French siege by supplying the City.

Rather than escaping Egypt to find conquests elsewhere, the French were forced to retreat to Cairo. Despite their earlier successes and the defeat of two Turkish armies, their expedition had turned from triumph to desperation.

A Beaten Army

The Army that retreated from Acre was in complete disarray. Hunger and plague were killing men in their droves. Stricken by disease, many sought an escape through opium to lessen their suffering on the way to the grave. Stragglers were cut down by the Turks. 1,200 of the sickest troops were loaded onto boats at Jaffa in the hope they might find medical care at Damietta. Some men committed suicide in front of their comrades rather than face a terrible death.

As they arrived at Cairo, Napoleon had his army greeted as conquering heroes taking part in a planned retreat. They all knew it was a lie. They were hungry, dirty, diseased, and demoralized. Only Russia would ever again bring a Napoleonic Army to such depths.

Egypt as Propaganda

Despite this, Napoleon turned the Egyptian campaign into a public image success. It stretched even his remarkable powers of propaganda, but he was willing to try.

At the heart of this effort lay two news sheets that he commissioned in Egypt.

The Courrier de l’Egypt was aimed at the troops and the ordinary citizens of France. It talked about the rich culture of the newly conquered lands, diplomatic successes with the locals, and Napoleon’s triumphs. It countered rumors of failures.

La Décade Egyptienne was more scholarly, reporting on the work of the 160 academics Napoleon had taken with him. It told of the amazing things being discovered in Egypt. Napoleon was shown as a scholar as well as a military hero.

Napoleon not only countered the damaging effects of his failure, but he also associated himself with the glamor of the east and the successes of French scholarship.

Escaping the Consequences

Napoleon consolidated his reputation through propaganda, but he escaped the physical effects far more directly. He left Egypt onboard a boat with a few of his closest companions, dodged the British Navy, and returned to France. His soldiers, having been abandoned by their heroic commander, had to make a grueling trek around the end of the Mediterranean before the survivors reached home.

Napoleon’s timing was as excellent as his propaganda. He returned to Paris apparently a conquering hero, just as French politics was entering another crisis.

Recruited by a group of conspirators, he became the military front of a coup. Napoleon then hijacked their efforts, resulting in him becoming First Consul of the Government of France.

Militarily, Egypt had been a failure for Napoleon. As far as his career was concerned, it was a success.

Sources:

Alan Forrest (2011), Napoleon.

Robert Harvey (2006), The War of Wars: The Epic Struggle Between Britain and France: 1789-1815.

Matthew D. Zarzeczny (2013), Meteors that Enlighten the Earth: Napoleon and the Cult of Great Men.