In 1807, Napoleon’s French armies crossed Spain to invade Portugal. It began a seven-year campaign known as the Peninsular War. For the Spanish, it was a deeply divisive period. Spaniards fought on both sides, resisting or supporting the French.

At the Start

At the beginning of the Peninsular War, France and Spain were allies. The Spanish had served alongside the French against Britain’s Royal Navy at the Battle of Trafalgar.

The Spanish were ineffective allies whom Napoleon could not rely upon. The deeply divided Spanish government included both pro and anti-French factions. Manuel Godoy, King Charles IV’s prime minister, wanted to abandon the alliance and invade France.

One of the reasons for Spain’s unreliability as an ally was the state of her armies. The Spanish royal finances were in a poor state, unable to support an effective military. A shortage of manpower added to the problems.

At the start of the war, some of the best Spanish troops were in Denmark and Germany under the command of the Marquis of La Romana. There, they were supporting their French allies.

When the French turned on their allies in 1808 and seized control of Spain, the results were disastrous for the Spanish. The French defeated poorly trained infantry that was supported by inadequate cavalry and artillery. General Benito San Juan was shot and hung from a tree by his own men as they believed he was going to surrender.

Much of La Romana’s force was withdrawn from northern Europe by the British navy, but the armies of patriotic resistance were still in a terrible state.

The Bonapartists

Having forced Charles IV and his son Ferdinand to surrender their throne, Napoleon installed his brother Joseph as King of Spain. With the peninsula full of French troops, many of Spain’s leaders decided it would be better to cooperate than to resist. Men such as General Gonzalo O’Farrill, the war minister, continued working for the new king.

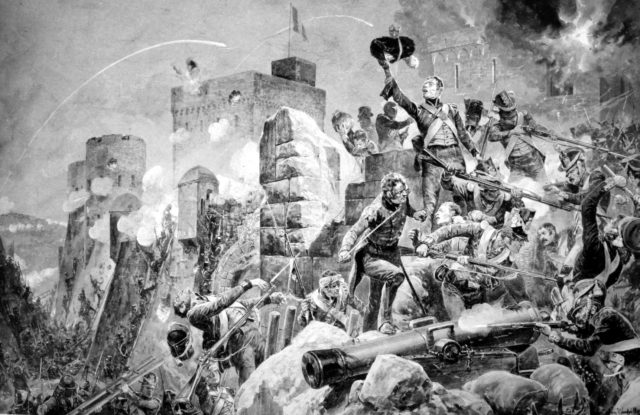

A large part of the army shifted to Joseph’s service. They served in battles such as the defense of Badajoz in 1812. They mainly did so as subsidiaries to the French army. Spanish line regiments remained less efficient than their French counterparts, their generals less effective, and their men less willing to fight. Their most reliable units included two regiments made up of foreign troops; the Royal Etranger and the Royal Irlandais.

The most reliable part of the army was Joseph’s Royal Guard, which he raised on his brother’s advice at the end of 1808. A mixture of Spanish and French troops, it consisted of elite units such as grenadiers and hussars. There was even a unit of halberdiers who had come with him from his previous post as King of Naples.

Wellington’s Allies

In 1808, the British joined the Peninsular War. Following initial failures, the campaign was taken over by Sir Arthur Wellesley, whose successes in the campaign earned him his better-known title of the Duke of Wellington.

While Wellington led the fight against the French, he was aided throughout by Spanish forces opposed to the French king.

The problems that had beset the Spanish at the start of the war continued to plague them. A shortage of resources was not helped by insurrections in overseas colonies, many of which saw revolutionary movements breaking out. Only a small number of troops from the colonies came to fight for the homeland, and the colonies were at times a drain on attention and resources.

The Spanish armies were under-equipped with both cavalry and artillery. The British helped with the latter, supplying cannons for the Spanish forces. In the beginning, many of the soldiers were poorly trained and led, although the direct experience of warfare helped to counter that.

There was one aspect on which the Spanish regulars could not be criticized, and that was their courage. Robert Blakeney wrote that “Courage was never wanting in Spanish soldiers,” even though they were often “barefoot, ragged and half-starved.”

Under leaders such as La Romana, the Spanish regulars achieved victories of their own. They also supplied additional forces in support of the British. They earned the respect of the Duke of Wellington, a hard man to please.

The Guerrillas

The most famous contribution of the Spanish came in the form of guerrilla warfare. The word guerrilla, Spanish for little war, entered into the English language due to the war.

Thousands of Spaniards under dozens of different leaders formed new groups to fight against French occupation. Men with nicknames such as Manco (one hand), El Empecinado (the obstinate), and El Pastor (the shepherd) created formations ranging from ragtag mobs ambushing French patrols through to regiments that were a match for regular troops.

The distinction between guerrilla and regular forces was not always clear. Some of the first groups to emerge were made up of professional soldiers from dispersed units, such as those led by Juan Diaz Porlier, El Marquesito. As the campaign advanced, many men found their old battlegrounds liberated and so joined the regular army, contributing both infantry and cavalry.

The guerrillas created fear and uncertainty among the French. They killed soldiers, disrupted supply lines, and distracted troops from other tasks. French units became bogged down in hunting them. Their presence undermined Bonapartist morale. General Francisco Espoz y Mina at one point claimed to have six French generals busy chasing him.

The guerrillas could be incredibly brutal to the hated occupiers. It led to atrocities and counter-atrocities on both sides, including murders of prisoners and civilians.

With different factions fighting on opposing sides, Spaniards fought Spaniards. Napoleon’s ambition and Britain’s opposition to it may have been the biggest drivers in the Peninsular War, but the greatest pain was inflicted upon Spain.

Source:

Alan Forrest (2011), Napoleon

Philip Haythornthwaite (2004), The Peninsular War: The Complete Companion to the Iberian Campaigns 1807-14