The twin battles of Jena-Auerstadt proved a major turning point for not only the Napoleonic wars, but also for 19th century Europe as a whole. Immediately, it brought about the end of Prussian resistance to Napoleon. But in the long term shocked the Prussian military system, showing their younger officers that something had to change. After this battle, Prussia began taking steps towards becoming the dominant military power in Northern Europe, eventually uniting all of the German states into the German Empire.

The War of The 4th Coalition, as the conflict between October 7th, 1806 and July 1807 was called, saw an alliance between Russia, Prussia, Great Britain, Saxony and Sweden against France. The Prussians first marched south on October 9th, as a show of force against Napoleon’s control over the Rhineland and Austrian territories. But the Prussian military wasn’t in a fit state for prolonged conflict at this point.

For most of the 18th century, the Prussian army had gained a reputation for the successful use of highly skilled mercenaries. Many of the Germanic states had armies for hire, and it was in no way hard to hire an army for a single campaign. Under Frederick the Great they enjoyed many victories in the Seven Years War. By the 4th Coalition, most of the Prussian general staff had come of age under Frederick the Great and were staunch traditionalists. Adding to this, was the disorganized command structure of the Prussian army. There were three chiefs of staff and endless squabbling between them. Because of this, while they had mobilized before Napoleon, they immediately lost the initiative. There were multiple plans of attack to defeat the French forces, but the high command couldn’t decide on which one to implement. This wasted precious time, and by October 13th, 1806 it was too late.

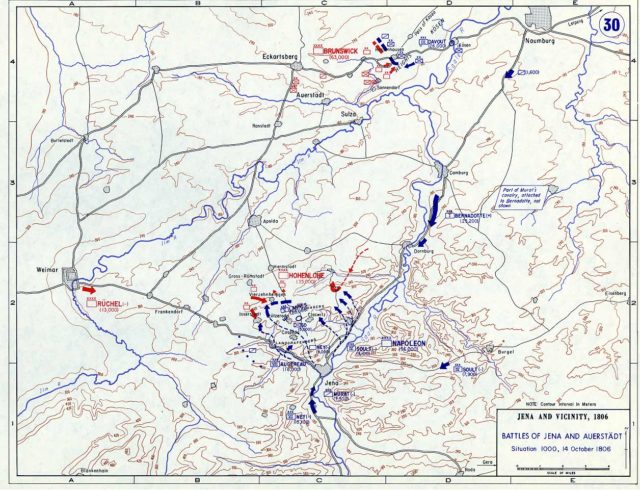

Napoleon’s forces had been marching north, with little resistance. One of his generals, Lannes, had found an advance Prussian force near the town of Jen on the 13th of October. He reported this to Napoleon, who ordered him to take up a strong position. The French troops took up a line of battle on the hills north of Jena, overlooking the plains below them. Initial contact was with only about 5,000 Prussian troops, with 15,000 marching up behind them. By the next morning, they would face around 40,000 Prussians, and Napoleon believed this to be the main enemy force in the region. He began pulling in his reserves, hoping for a decisive victory to crush the Prussians early on.

Louis Nicolas Davout, the commander of the III Corps, received orders to march from his position at Naumburg, north of Jena, to Apolda. Napoleon wanted this force, only 27,000 men, to encircle the Prussians retreating from Jena, to fully secure the victory. Davout’s troops set out around 0400 on the 14th, headed southwest.

Two hours later, Lannes, under orders from Napoleon, advanced towards the Prussians. Along with the French generals Suchet and Gazan, he captured the towns northwest of Jena. But the Prussians counterattacked and forced Lannes, who had pushed out past the French line, to fall back in line with Suchet and Gazan. The Prussians then pushed the attack, but were repulsed by French light infantry which had been hidden from view. Marshal Michel Ney now arrived on the battlefield, with an additional 3,000 men.

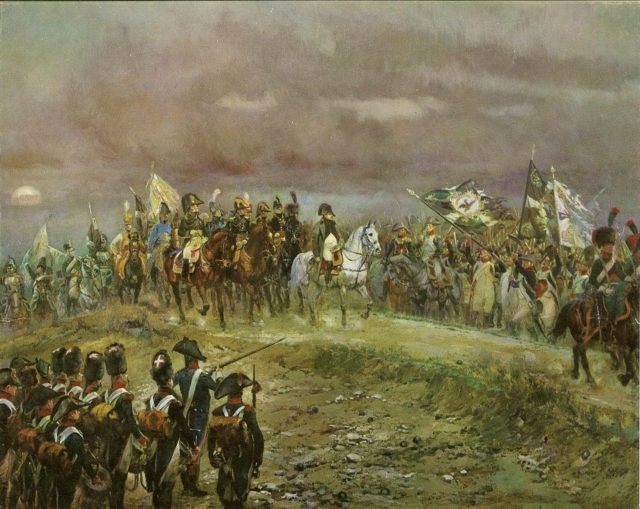

He was originally ordered to support Lannes’ right flank, but seeing that Suchet was already in position there, moved to the left. He pushed out past the French line with a combination of infantry and cavalry. While he was initially successful, he overextended himself and was quickly encircled by Prussian troops. Napoleon ordered units from the center to reinforce Ney’s weakened position, giving him a chance to retreat. This left the French center exposed, but Napoleon sent his Imperial Guard into the gap.

The Prussian infantry could have exploited this weakness, but their leaders were sticking too stiffly to their plan, and leaders in the field had too little opportunity to use their own initiative. This would eventually cost them the battle, as the French were able to solidify their position, and repulse the ensuing Prussian assaults. By the end of the day, the French had broken the Prussian line, killing 10,000 men, taking 15,000 prisoners, and capturing 150 pieces of artillery at Jena.

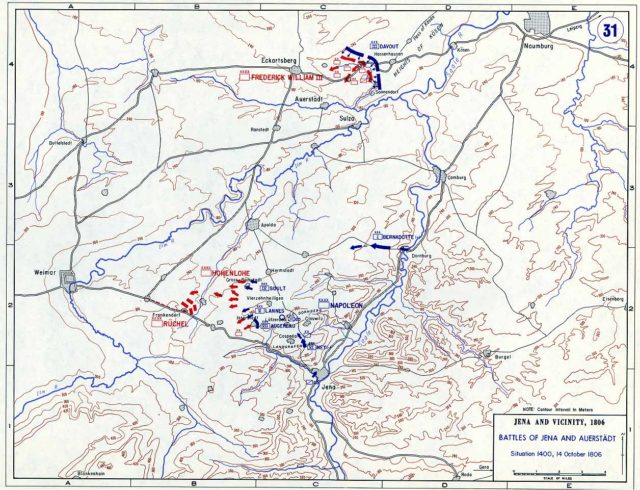

During all of this, another battle was raging to the north. Davout’s III Corps had come in contact with Prussian cavalry and artillery early in the morning and formed a defensive position at Hassenhausen. The Prussians were initially successful, with around 50,000 men, had nearly twice that of Davout. They forced the French into the town of Hassenhausen itself. Then everything went downhill for the Prussians.

Davout’s forces arrived in full around Hassenhausen. Their artillery had come into position, and they were ready to put up a defense. The Prussians attempted to launch a large-scale assault, but due to poor communication couldn’t coordinate between commanders. Their cavalry attacked to the north, only to be met by squares of French infantry. The Prussian infantry attacked to the south, but both were repulsed.

By 1100 it was clear that the Prussian troops were wavering, two of their commanders had been mortally wounded, and the Prussian king Frederick William assumed command. But the King was wrongfully convinced he was facing Napoleon himself, which terrified him. He refused to make a large scale attack, for fear that the French would have a trick up their sleeve and counter. The French then launched a full-scale attack, breaking the Prussian line, and seizing the day.

In all the Prussians lost 13,000 men near Auerstadt and another 20,000 near Jena. But Auerstadt proved to be the most humiliating defeat, for they nearly outnumbered their opponents 2 to 1. After this day, it became clear to a small group of younger Prussian officers that something had to change. Gebhard von Bluecher, Carl von Clausewitz, August Neidhart von Gneisenau, Gerhard von Scharnhorst, and Hermann von Boyen were all present that day.

These would later create a reform committee which revolutionized the Prussian military. They realized that mandatory service was necessary, that individual initiative needed to be taken by commanders at the front, and reliance on mercenaries and conscripts wasn’t a viable option anymore. Their reforms set the stage for Prussia’s military might in the rest of the 19th century, eventually allowing them to crush the French in the Franco-Prussian war, establishing the German Empire as the military powerhouse on the continent.