It is a common misconception that the Navies of the Napoleonic Wars used only massive ships, crewed by hundreds of men, which would slowly close and pass their enemy in a line of battle. In truth, every Navy employed a broad range of craft, and many experimented with varying designs, resulting in either astounding success or crushing defeat. Here is a brief description of the variety of ships used during this period, although it only scratches the surface of what was in use.

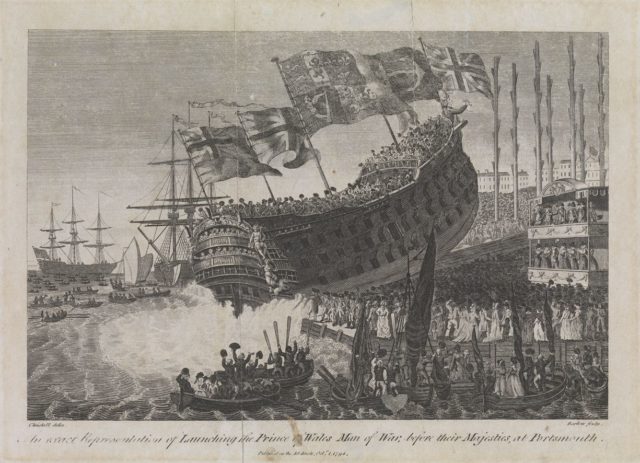

We begin with the largest, and most well-known: ships of the line of battle. Since the mid 17th century Navies had adopted a line-of-battle in major fleet actions. Each adversary formed a continuous row of powerful warships; the two lines approaching one another, each trying to outmaneuver the other. Early on, any ship available was used in these lines, but it became evident that purpose-built line of battle ships (where the modern term “Battleship” comes from) were needed.

The largest were 1st class ships of the line, three-decked, with upwards of 100 guns. These were the real battleships of the age, massive floating fortresses which formed the initial punch behind an attack. These ships, being so high above the water, were cumbersome, bulky, slow moving, and unstable. They could barely be handled in rough weather. They were usually utilized as a command ship for an Admiral or Commodore.

Their substantial size ensured they could be seen from anywhere on the battlefield and proved an impressive sight for any enemy not expecting to see such a massive ship.

Supplementing the 1st class, came the 2nd, 2-3 decks, from 84-98 guns. These proved to be slightly more useful in a chase, being somewhat lighter. They were intended for pitched battles and major fleet actions. These were the heavy hitters in a line of battle.

Taking Trafalgar as an example, there were three 1st class ships, supplemented by four 2nd rates. They were used to deliver a punishing broadside, outweighing almost anything else on the seas, weakening an opponent and opening them up to attacks from other ships.

Next, logically, came the 3rd rates, who made up the rank and file of a line of battle. Always two-deckers, with between 64 and 80 cannons. The most common had 74 guns and were around 170 feet along the gun deck. This provided a balance between the firepower needed in a line of battle, and the maneuverability necessary for mopping up and chases which occurred after a major fleet action.

The 1st and 2nd rate ships were too clumsy for this duty, but a well manned and handled 74 gunner could skirt around an enemy of equal size, and even outmaneuver some of the smaller ships if the wind was in her favor. At Trafalgar, in 1805, 20 of the 27 British ships of the line were 3rd rates, and 16 of those had 74 guns.

Between 3rd and 4th rates there was an ambiguous class of “razeed” 3rd rates. These were 3rd rate two-deckers which had their top deck removed, making them faster and more stable in rough seas. These ships had between 44 and 58 guns and filled two distinct roles. Those converted to 44 guns were used as frigates.

The 58 gun 3rd rates, while they were no longer deployed in lines of battle, provided an important source of heavy firepower for smaller fleet actions and convoy protection.

Finally came 4th rates, two-deckers with 50 guns, essentially heavy frigates. These were too small to be considered a line of battle ship, but would often be used in minor fleet actions, forming the command ships in frigate actions.

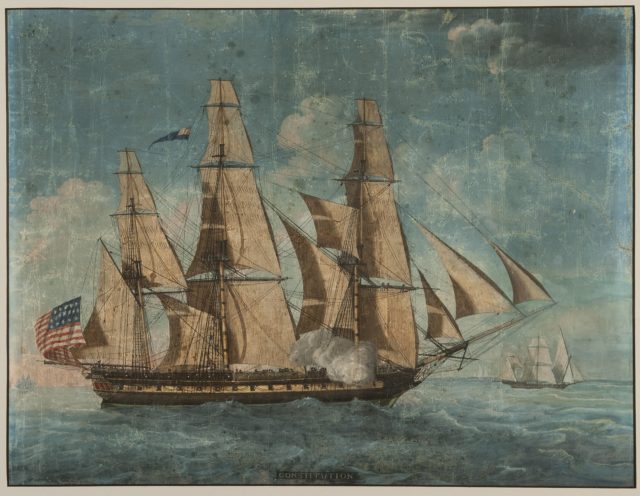

Following these are the frigates, a widely used and often misunderstood term. Officially, since the 1750’s, it meant any ship of 28 to 48 guns but, in practice, it could refer to a ship with as few as 20 guns. These were the pursuit ships, tasked with hunting down enemy convoys, merchant fleets, and lone warships. Designed for maneuverability and firepower they had a single gun deck, with additional guns on the forecastle and quarterdeck. Early frigates were armed with nine pounder cannons, meaning they fired a 9-pound ball of iron, lead, or stone.

As the naval arms race at the end of the 18th century called for bigger and better ships, 12, 18, 24, and even some 32 pounder cannons began to appear. Often a ship would carry a variety of guns onboard. This enabled them to pick off enemies at a distance, with a longer nine pounder cannon, or bash in a hull at close range, with a 24 pounder shot at only a few yards away.

Design development of frigates in this period produced the USS Constitution, an American single decker, with 44 guns launched in 1797. She represented a new construction method, allowing for a longer thinner ship, which handled better than almost any other ship of her class. Her hull was also much thicker than her counterparts in the Royal Navy, earning her the title of “Old Ironsides,” when cannon balls rolled down her sides during the War of 1812.

It took most other navies over three decades to adopt this new method of construction, giving the Americans a distinct advantage in this period, despite their lack of larger ships.

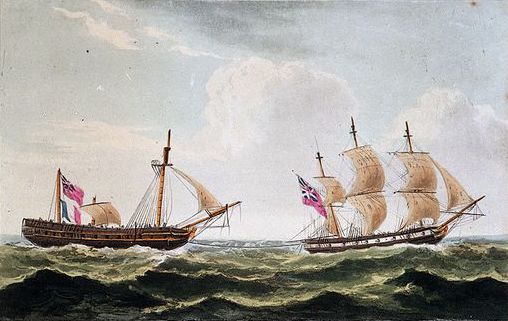

Below frigates were post ships, of 20-26 guns, essentially small frigates. These were not intended for fleet actions, or even single ship actions, but protected shipping lanes. Merchant shipping lanes provided supplies to the far-flung stations of both the British and French Empires but proved very vulnerable to enemy attacks. They were powerful enough to take on the coastal sloops and brigs which came out as raiders. Their lack of speed did not hinder them when protecting slow moving merchants.

The term “post ship” comes from the fact these were often the second command of Royal Navy officers. An officer would be made Commander and given the command of a smaller sloop or brig. If he proved himself, he could be made Post Captain and given a post ship.

All the previous ships, from the largest ship of the line, down to post ships, were full-rigged, meaning they had three masts, all rigged with square sails running across the ship. Those below post ships, include: Sloops of War, Gun Brigs, brigs, schooners, and cutters.

Sloops of War were where a Commander would start his career, but the term is something of a misnomer. A sloop is technically a single masted ship, but Sloop of War was a generic term encompassing two masted Brig-sloops and Bermuda Sloops. A Brig Sloop was a brig-rigged vessel, meaning two square-rigged masts (large sails running across the ship).

These were the most common, and the Royal Navy built many of the Cruizer class, which proved highly effective at raiding enemy shipping. Their range, both in firepower, and cruising distance was very limited, but they proved highly useful for coastal raiding and patrols.

The key advantages these ships had was their speed and maneuverability; they were able to slip past the larger, slower post ships in convoy, and strike at smaller, undefended merchants. Good luck to any lone merchant who ran into one of these fast, well-armed ships.

Gun Brigs filled a similar role, but with a focus on heavier cannons. They mounted two long guns in the bow for chasing, and ten carronades (shorter, fatter cannons which packed a more powerful punch at short range) in broadsides. They were fast and maneuverable, the idea being to get in close to an enemy, and open up with the carronades.

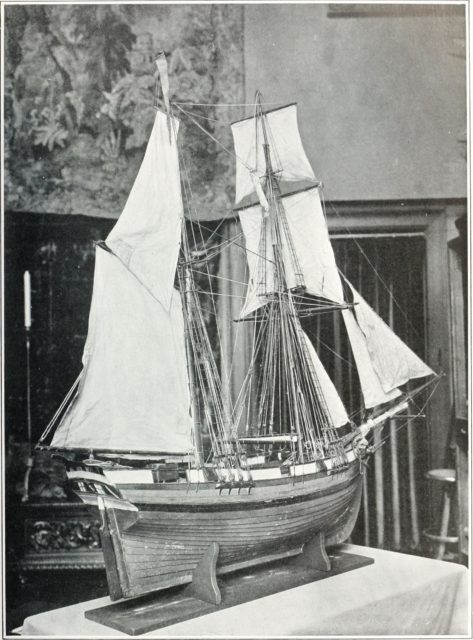

Finally, brigs, sloops, cutters, and schooners. These filled the supporting roles of a navy, being able to ferry supplies, troops, and most importantly, information around the fleet.

Packet ships, fast, small ships designed to traverse the Atlantic, were of the utmost importance at the time, and almost all news, from around the world, was transported on such vessels. The Royal Navy specifically protected Packet ships, understanding their importance for a continuous flow of information around the British Empire.