The success of Napoleon Bonaparte stands as a testament to his extraordinary talent as a general. For twenty years, his armies dominated the battlefields of Europe. Both the skill and the style of warfare he undertook transformed the way that wars were fought.

But Napoleon didn’t exist in a vacuum. So was he really a great innovator, or was he just the best at applying the techniques others had come up with?

Manoeuvrability

Strategically, Napoleon relied upon the maneuverability of his armies. By moving fast and flexibly across the landscape, they were able to fight the enemy in circumstances of his choosing, setting the French up for success.

This was in part a divide and conquer strategy. Moving quickly allowed Napoleon to fight enemy forces one at a time, rather than letting them come together to use their united weight of numbers. Even in his eventual defeat in the Hundred Days, he managed to avoid fighting the Prussians and English together until the end of the Battle of Waterloo, the dying moments of his campaign.

The way Napoleon’s armies moved was hardly unprecedented. They used the same technology and logistics as predecessors such as Frederick the Great. In this area, the real innovations would come long after Napoleon’s downfall, when the careful use of railways transformed the process of getting troops and supplies into position.

Yet there was something innovative about Napoleon’s armies that allowed them to be more maneuverable, and this was the use of large mobile corps.

Usually consisting of between 20,000 and 30,000 men and led by one of the empire’s prestigious marshals, these corps were effectively small armies in their own right. Because of their scale and high-level leadership, they could achieve swift and flexible strategic maneuvers while still facing an army when required. Combining in the bataillon carré, in which several corps marched separately but close enough to support each other, this allowed both flexibility and concentration of strength.

Using Initiative

Flexibility of planning was key to Napoleon’s success. This was less an innovation and more a matter of personal ability. He went into battles with a plan, which he then adapted in the face of the enemy. This let him make the best use of the specific circumstances he faced.

Unfortunately, his desire to respond to events prevented his subordinates from being given great initiative or developing this skill. This was demonstrated in Portugal and Spain, where the removal of Napoleon from the equation highlighted the poor judgment of some senior commanders.

Artillery

Napoleon’s background as an artillerist has led many people to focus on this element. Yet the quantity and quality of guns in his armies was not hugely different from what came before, or from what his contemporaries used. With three guns for every 1000 soldiers, he deployed a volume of artillery not much greater than that of the old regime.

While there were improvements in technology over the course of the wars, the range of these guns remained limited to around half a mile.

Where Napoleon did innovate was in concentrating the firepower of his guns. Rather than dispersing them among the infantry, he gathered guns together into substantial batteries that allowed him to achieve local superiority in areas of the battlefield. Concentration of fire was Napoleon’s great artillery innovation, and it was a valuable one.

Columns

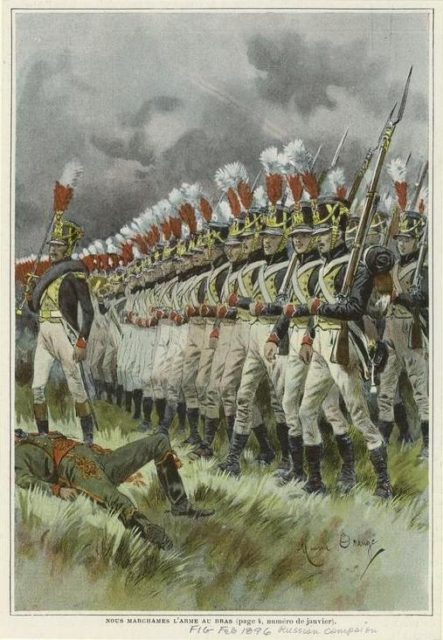

French infantry fought differently from their peers. Gathering into columns, they sacrificed frontline firepower for a shock charge that punched through thin enemy gun lines.

This innovation is associated with Napoleon, thanks to the success with which he used it. But it was not his creation. Rather, it had been suggested by his predecessor Guibert. Napoleon took a tactic someone else had developed and deployed it effectively, letting his troops do things others could not.

Skirmishers and Light Troops

The most significant change Napoleon made to the troop mix of his army was an increase in skirmishers, including light infantry, fusiliers, and grenadiers. Cavalry, sometimes used for shock charges, were at other times deployed in this role.

These skirmishers allowed Napoleon to achieve his most notable victories, those against numerically superior armies. First, he would send skirmishers forwards to find the enemy positions and engage the opposing front line while keeping most of his troops back. The main French army and its reserves were concealed so that the enemy would not know where they were coming.

Having launched a frontal assault, he would then launch a surprise attack on a flank using the troops he had held back. As the enemy rushed to bolster that flank their center would be weakened, letting him commit his reserves for the final breakthrough.

Artillery, cavalry, and line infantry all played a part in these successes. But it was the light infantry that achieved the key step of drawing the enemy into combat while keeping the main force concealed.

Adaptor or Innovator?

So was Napoleon an adaptor or an innovator?

The truth is that he was a bit of both. Building upon lessons from men such as Frederick the Great and Guibert, he created an army that was both tactically and strategically flexible, as suited his style of command. He was a leader in the trend towards more light troops, but these were not novel in themselves. He used similar artillery to his peers but deployed it far more effectively.

His ability to adapt and to innovate declined as his career went on. His opponents learned from him, adopting elements of his way of fighting and countering others. Unable to develop new techniques, he instead fell back on a classic – massed charges that relied on crude force rather than tactical thinking. Such an approach cost France greatly at Aspern-Essling (1809) and Borodino (1812), and would lead to huge sacrifices on the field of Waterloo.

The early Napoleon was a gifted adaptor and innovator. The later Napoleon was a man stuck in a rut, facing opponents who had wised up to him.