The Battle of Waterloo took place on June 18, 1815, in a gently sloping valley around six miles south of the city of Brussels in what was, at that time, the United Kingdom of the Netherlands.

The battle involved a confrontation between an Anglo-Dutch force under the command of Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington, French forces under the command of Napoleon Bonaparte, and Prussian forces under the command of Field Marshall Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher.

Most historians and scholars will agree upon these basic facts, but almost everything else is open to question. Like most significant historical events. it isn’t just the raw data that’s important here, it’s also the context and the interpretation of these facts that define what we think we know.

Let’s take a look at three quite different views of what happened at the Battle of Waterloo. These are simplified and drawn from a number of sources, but they do represent a reasonably accurate summary of the very different national accounts of the battle.

British and Dutch version

The Anglo-Dutch army was outnumbered by their French opponents on the field at Waterloo. The combined forces commanded by the Duke of Wellington numbered around 78,000, and they faced 84,000 French troops under Napoleon.

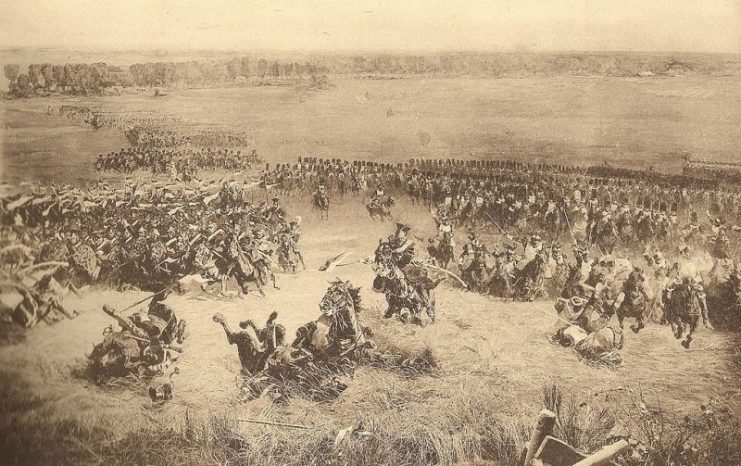

The battle commenced at around 11:30 and the Anglo-Dutch lines withstood a number of heavy French attacks before the elite Old Guard was sent out in a final, desperate attempt to break through before the arrival of the Prussians.

This failed, partly due to the tactical genius of Wellington, and Anglo-Dutch forces advanced to sweep up the remnants of the French army just as the Prussians arrived. The 1970 movie Waterloo broadly follows this scenario.

A contemporary British newspaper report modestly said of the battle: “Britain, therefore may indeed now be truly considered as at the summit of glory. Having saved herself by her own exertions, she has saved Europe by her example and support, and to her generous and noble sacrifices will Europe and the world be indebted for the overthrow and annihilation of the curse and scourge of the human race.”

French version

The French Army was massively outnumbered on the field at Waterloo. A French army of around 70,000 faced anything up to 120,000 Anglo-Dutch troops supported by an additional 30,000 Prussians.

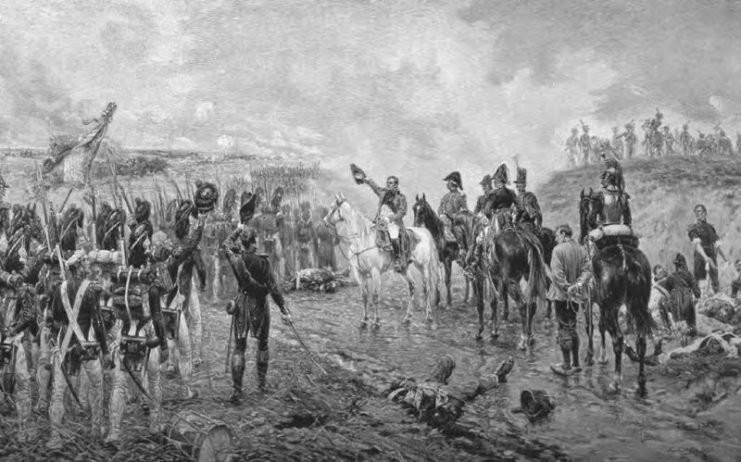

Despite facing odds of more than two-to-one, the tactical genius of Napoleon meant that the French came very close indeed to a complete victory and were defeated only by sheer force of numbers.

In a later account of the battle written during his exile on St. Elena, Napoleon wrote: “The French army, 69,000 strong, which at seven o’clock in the evening was victorious over an army of 120,000 men… saw the victory snatched from it by the arrival of Marshal Blücher with 30,600 fresh troops, a reinforcement which increased the allied army in line to nearly 150,000 men, that is to say in a proportion of two and a half against one.”

Prussian Version

The Prussian army was outnumbered by the French forces comprising a blocking force under the command of Grouchy as well as the main force under Napoleon. The French were on the point of defeating the Anglo-Dutch army when the Prussians arrived in the nick of time and attacked Napoleon’s right flank at Plancenoit.

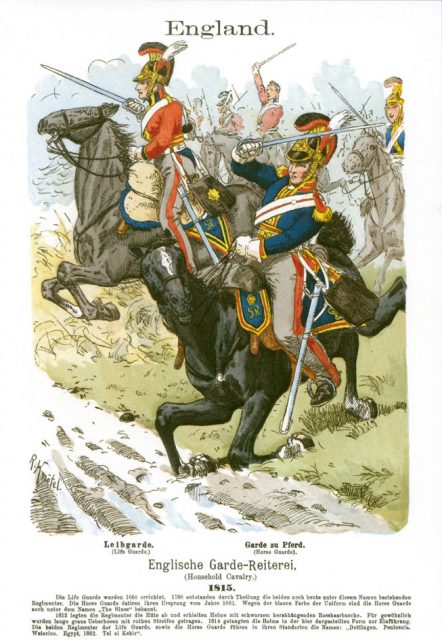

This version of the Waterloo story also notes that parts of the Anglo-Dutch army were German-speaking – the King’s German Legion, for example, defended La Haye Sainte.

In fact, this version points out that there were more German speakers on the Allied side than British, and one of the most popular German books about the Battle is titled 1815: The Waterloo Campaign: The German Victory.

Writing after the battle, General von Gneisenau, Blücher’s Chief of Staff, said of Wellington’s claim that this was a British victory: “The worst behavior has come from Wellington, who without us would have been smashed to pieces.”

Just the Facts

If we accept that there are at least three quite different interpretations of what happened on June 18, 1815, surely all we have to do is analyze the facts to see who is telling the truth. If only it were that simple.

Take the notion of just who was or wasn’t outnumbered on the field at Waterloo. Napoleon claimed that his forces comprised less than 70,000 combat troops who were facing an Anglo-Dutch army of 120,000 men before the arrival of the Prussians.

However, Wellington claimed that his army of 78,000 men faced around 84,000 seasoned French troops. Clearly, both these views can’t be true so which is correct?

Part of the issue is a force of somewhere between 17,000 and 20,000 British troops which Wellington placed to the west of the main battlefield under the command of Prince Frederick. Their purpose was to guard the route to the sea which British forces would have taken if they had been forced to retreat.

These were combat troops, but they took no part in the fighting on the 18 of June. Wellington didn’t count these troops when claiming that the Anglo-Dutch Army was outnumbered by the French; Napoleon did when claiming precisely the opposite.

That’s partly why each side claimed to be outnumbered during the battle. Which view we decide to accept probably depends on our own bias and background. I’m British, so I understood the Battle of Waterloo to be an Anglo-Dutch victory against a larger French Army, with the Prussians lending support once that battle had already been decided.

I was surprised to learn that people in France and Germany had a very different view not only of the battle but also of what I believed were key events.

For example, Wellington’s order to the commander of the First Brigade of Guards to advance, “Now Maitland, now’s your time!” is seen in most British accounts as the decisive moment what the battle was won. In French and German versions, it barely merits a mention and is not seen as especially important.

All history is characterized by interpretation. Military history is even more subject to the particular view of the historian. Facts are easy to find, but what they add up to is rarely simple or straightforward.

Perhaps Wellington was right after all – he believed that it was impossible to produce a reliable account of something as intrinsically chaotic as warfare. In a letter written to a friend two months after Waterloo he noted:

“The history of a battle, is not unlike the history of a ball. Some individuals may recollect all the little events of which the great result is the battle won or lost, but no individual can recollect the order in which, or the exact moment at which, they occurred, which makes all the difference as to their value or importance.”