Graf Spee’s eagle is once again in the news, and once again their notorious legacy is causing controversy.

The government of Uruguay has in its possession a massive, 800-pound, bronze Nazi eagle, recovered from a German battleship Graf Spee recovered off the coast of the South American nation.

But the German government is not happy with its court’s decision that Uruguay must sell or auction off the eagle, as it has long held that Nazi items should not be sold, or exhibited in public unless it’s in appropriate arena.

Obviously, Germany’s Nazi past is something that still causes deep, national shame, and officials try to lay claim to any of the symbols, valuable or not, that are part of that heritage. In this case, the eagle is very valuable indeed; it is worth up to $76 million according to some estimates.

Placing it in the appropriate historical facility, such as a war museum that does not shy away from the brutality of the Nazi regime, is how the German government would prefer to have it exhibited. If, that is, it is exhibited at all.

https://youtu.be/dt5xdqwmMsw

The bronze bird’s talons sit atop a swastika, another grim symbol of the Nazi party that was placed on everything from ships to uniforms. As the ship’s tailpiece, it effectively “announced” Germany’s presence on the high seas during World War II.

The eagle has been kept in a Naval storage facility since the battleship’s recovery process concluded; it began in 2004 and ended with the eagle’s recovery in 2006. Removing the ship was urgent, as it was in the midst of shipping lanes and posed a serious threat to commercial vessels in the area of Montevideo Harbour.

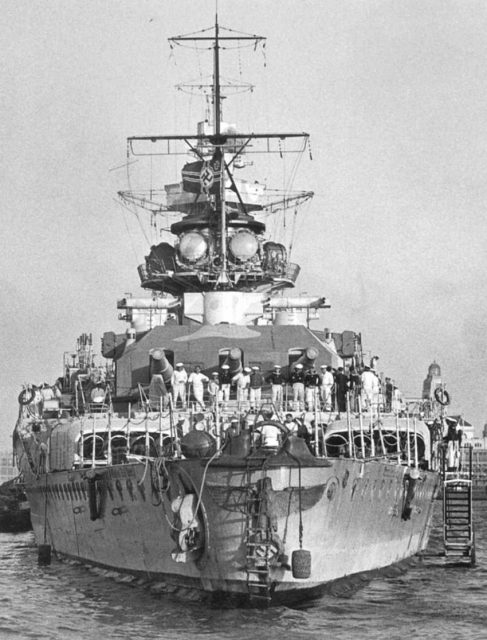

The “Graf Spee,” had sunk Allied ships in the South Atlantic, but was finally hit – but not sunk – by three Allied vessels in 1939, one from New Zealand and two from Britain. However its captain, once the crew was removed, sank the boat; he killed himself shortly afterwards in a Uruguay hotel room.

This project was funded, in part, by private money in addition to government funds. But since 1973, the Uruguay authorities has laid claim to any and all wrecks found in its waters, so by the country’s laws, the eagle’s fate is entirely up to them.

However, the German government is decidedly unhappy with this recent turn of events. In fact, when the eagle was put on exhibit for a brief period in 2006, German officials objected so vociferously that it was removed from display.

In 2006, other items from the wreck were also salvaged, including a communications tower and a cannon, neither of which caused any controversy. The eagle, however, is different to everyone – the government, the investors in the salvage project, Jewish groups, and historians.

Talk surfaced then of selling the eagle, but the government intervened, according to the New York Times (NYT), which published a piece on the debate.

At that time, many government officials expressed worry that Neo Nazis might buy the eagle, or any of the ships’ objects.

“There are ethical limits on the promotion of Nazi symbols in museums, so who are the potential buyers of these (items) if not Neo Nazis?” wondered Miguel Esmoris, director of the National Heritage Commission in an interview with the Times in 2006. “We are not against salvagers making a profit, but this is formally an archaeological site, and we cannot allow illicit trafficking in cultural and historical items.”

Others took issue with the sale, too. Roberto Bracco, a marine archaeologist also interviewed by the NYT, said, “I’ve received emails from colleagues in Europe saying that Neo Nazi groups there are very interested in acquiring the eagle,” he stated.

“This shows that the past, especially the recent past, must be carefully managed, and that Germany, Britain and the Jewish community all need to be involved in the disposition of these items.” One Jewish official, Ernesto Kreimermann, then-president of the Uruguayan Jewish Committee, concurred with Bracco.

He told the NYT: “We do not object with the recovery process itself,” he insisted. “This vessel is an historical artifact that offers testimony to one of the darkest periods of modern times.

But when it comes time for commercialization of the insignia, we believe that it must go to a museum, not into private hands, and that photographs (must) be carefully controlled.”

One Uruguayan, an 88-year-old former torpedo mechanic, told the Times, “this is madness,” meaning the entire project. “It’s too expensive, and senseless.”

Twenty-two years have passed since the eagle was discovered, and many still feel it is appropriate that the symbol, which is an imposing nine-feet in height, should land in an environment that not only understands its ugly historical significance, but is capable of controlling its image.

Is it fair that private investors lay claim to it just because they have spent money on its recovery?

Or is more appropriate – and more morally correct – for the Jewish community to decide its fate? Or should it be returned to Germany, as the country continues to struggle with its “sins” of almost 80 years ago?

The solution is still not known, but the courts have now forced the Uruguayan government’s hand, and it will indeed be sold.

Another Story From Us: The Hunt for the Pride of the German Navy – Admiral Graf Spee

Proceeds from the sale, which must occur approximately by the end of September, will be returned to the original investors. But what happens to the eagle after that? No one can say yet with any certainty.