Irmgard Furchner, a former German secretary who worked at Stutthof concentration camp in northern Poland during the Second World War, has been convicted and sentenced for her complicity in the deaths of 10,505 prisoners. The 97-year-old worked as a shorthand typist between 1943-45.

Irmgard Furchner is the first woman in decades to be tried for war crimes committed during World War II and is the first civilian female to be held accountable for her actions at a German Army-run concentration camp. As she was just 18 or 19 years old at the time, she was tried in a special juvenile court.

The trial was delayed until September 2021, as Furchner had fled from her retirement home in the German town of Quickborn, prompting the presiding judge to issue a warrant for her arrest. She was eventually located on a street in Hamburg and placed in provisional detention.

The 40-day trial occurred in two-hour increments, given her age, and heard from 30 survivors and relatives of those who had perished at Stutthof. It also heard testimony from several historians, who recounted daily life at the concentration camp and the role Furchner played in the bureaucratic processing of prisoners and their treatment.

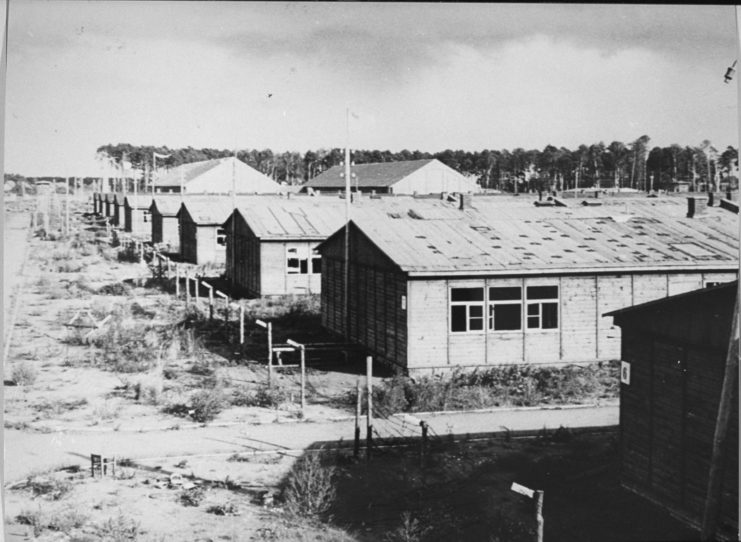

Stutthof was located near the modern-day city of Gdańsk, Poland. It originally served as a civilian internment camp under the control of the Danzig police chief, but was turned into a “labor education” camp, similar to Dachau, following its expansion in November 1941. It subsequently became a concentration camp a few months later, in January 1942.

Inmates from 28 countries were imprisoned at Stutthof, including Jewish citizens, Red Army prisoners of war (POWs) and Polish elite from Danzig and Western Prussia. The majority of prisoners – between 63,000 and 65,000 – perished during their time at the camp, with many dying of starvation, disease and exposure to the elements. Many more perished when gassing with Zyklon B was introduced to the complex in June 1944, while others were shot in the back of the neck.

In January 1945, as the Red Army advanced deeper into Germany, nearly 50,000 prisoners were evacuated and forced to march toward Lauenberg. However, they were cut off by the advancing troops, prompting the Germans to return the captives to Stutthof. A second evacuation occurred in April 1945, with the Germans loading prisoners into small boats. Those not shot were sent to Neuengamme and other camps along the Baltic coast.

It wasn’t until May 9, 1945 that the Soviets liberated the camp, rescuing around 100 prisoners who’d managed to hide.

Historian Stefan Hördler and two judges visited Stutthof and confirmed Irmgard Furchner would have been able to see some of concentration camp’s worst conditions from her position in commandant SS-Obersturmbannführer Paul-Werner Hoppe’s office, which served as the “nerve center” of the complex.

Presiding judge Dominik Gross said it was “beyond imagination” that Furchner couldn’t have noticed the stench of death and smoke coming from the camp’s crematoriums. “The defendant could have quit at any time,” he added.

The ex-secretary’s defense lawyers didn’t deny that war crimes occurred at Stutthof, but said Furchner herself wasn’t guilty of them and argued for her acquittal. Following the war, she married SS squad leader Heinz Furchstam, whom she likely met at the camp, and found employment as an administrative worker in a small town in northern Germany. Furchstam died in 1972.

At the end of the trial, Irmgard Furchner was found guilty of aiding and abetting the murders of 10,505 people and complicity in the attempted murder of five others. She received a two-year suspended sentence. At the end of the court proceedings, the 97-year-old broke her silence, saying, “I’m sorry about everything that happened. I regret that I was in Stutthof at the time – that’s all I can say.”

The verdict and sentence were in line with what prosecutors were seeking.

More from us: Ex-Concentration Camp Guard Sentenced to Five Years in Prison By German Court

Following the sentencing, Josef Salomonovic, a survivor of Stutthof, shared his feelings regarding the ex-secretary’s guilt. His father was killed by lethal injection at the camp in September 1944. “She’s indirectly guilty, even if she just sat in the office and put the stamp on my father’s death certificate,” he said.

Another survivor, Manfred Golberg, scoffed at the sentence, telling the BBC, “It’s a foregone conclusion that a 97-year-old would not be made to serve a sentence in prison – so it could only be a symbolic sentence. But the length should be made to reflect the extraordinary barbarity of being found to be complicit in the murder of more than 10,000 people.”