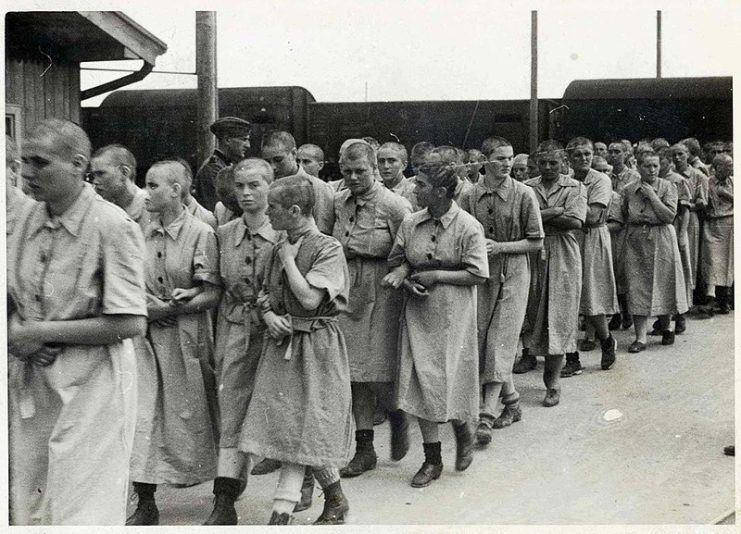

On July 13, 1942 Nemirovsky was arrested, and on July 17 was put on Convoy No. 6 for Auschwitz.

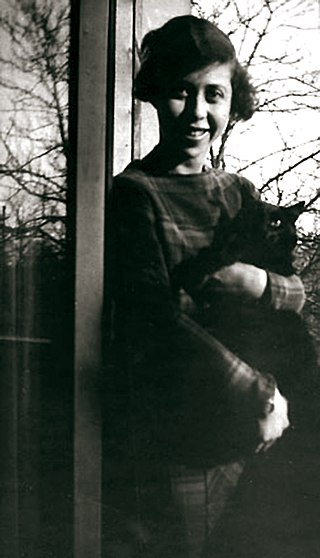

In 1930 Irene Nemirovsky’s debut novel David Golder was an absolute sensation, catapulting the young Parisien socialite into the French literary elite. By the time the book had made it to the silver screen in 1937 she had published nine novels, but her rising star faded at the outbreak of war.

The story she is best known for today, ‘Suite Francaise’ was not published until 2004, more than six decades after her death in the Auschwitz concentration camp.

Nemirovsky was born in Kiev, Ukraine, then part of the Russian Empire, into a world of privilege and luxury. Her father, Leon, was the president of a Russian bank and said to be one of the wealthiest men in the country.

Unfortunately, as the Russian Revolution gathered pace, the family found themselves living under siege conditions, hiding out in their Moscow townhouse while street battles raged all around them.

In 1917 the family was forced to flee, disguised as peasants, and entered Finland before the borders were closed. For a year they lived out a quiet life in a tiny three-house hamlet, waiting for the situation to settle down at home.

However, the Bolsheviks decided to put a bounty on Leon Nemirovsky’s head and so, after three months in Stockholm, Sweden and a stormy ten-day sailing, they arrived in Paris in 1919 when Irene was sixteen years old.

Fast forward twenty years and Irene is a literary star, married with two small daughters and settled in an apartment on the left bank of the Seine. But there were dark clouds massing on the horizon, and the political and racial tensions prompted Irene and her husband Michel Epstein to convert to Catholicism, with the entire family christened on September 2, 1939.

Nonetheless the Nazi German occupation of Paris in June 1940 pushed the family out of the city, and it seemed that history was repeating itself as Irene was on the run again. In October of that year a law was passed determining who could be classed as Jewish, along racial lines. Irene’s husband had to leave his job as banking was being “Aryanized,” and as a Russian Jew, Irene could no longer be published.

In June of the following year a further law stipulated internment or deportation for Jews. The four members of Nemirovsky’s family wore the Jewish star sewn onto the fronts of their coats, but life went on and Nemirovsky continued to write in her leather-bound notebook, keeping her script small and neat in order to make the most of every page.

It was during this exile from Paris that she began her most ambitious novel. She based the structure on Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony and dreamed of a book a thousand pages long.

The opening “movement” of the “Suite” is called “A Storm in June” and casts a pitiless eye over the events culminating in the Nazi occupation of France. She deftly describes the chaos as people of all classes flee before the enemy, some with cars piled high with mattresses, some struggling stoically with suitcases.

In the second section, “Dolce,” she turns her laser-like gaze onto an occupied village, the women charmed despite their best efforts by the refined Prussian manners of the German officer class.

On July 13, 1942 Nemirovsky was arrested, and on July 17 was put on Convoy No. 6 for Auschwitz, leaving her family and everything she owned behind her. Her husband shared the same fate just a few months later. Their daughters Denise and Elizabeth, then thirteen and five years old, escaped with a suitcase which held their mother’s notebook.

Read another story from us: Saving Anne Frank’s Diary

The daughters did not open the book for six decades, believing it was simply a private memoir. In the early 2000s, they decided it should be donated to a historical society. After the death of her younger sister, Denise discovered Suite Francaise, a blistering, savage and visceral prize-winning unfinished masterpiece, which became a runaway best seller and a hit film.