In 1941, Hitler’s Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union. The Red Army found themselves in desperate need of German interpreters.

Elena Kagan was a Russian Jew who signed up for a military translation course and was noticed for her skill with the German language. She was offered a role in Moscow but insisted on going to the front lines.

In January of 1942, she was sent to Rzhev. The Germans considered Rzhev a “springboard” to getting to Moscow. Stalin ordered that it be liberated at any cost.

The 17-month battle over Rzhev and the surrounding area contained some of the bloodiest fighting of WWII. Even so, the Soviets did not even include the battle in their official history books.

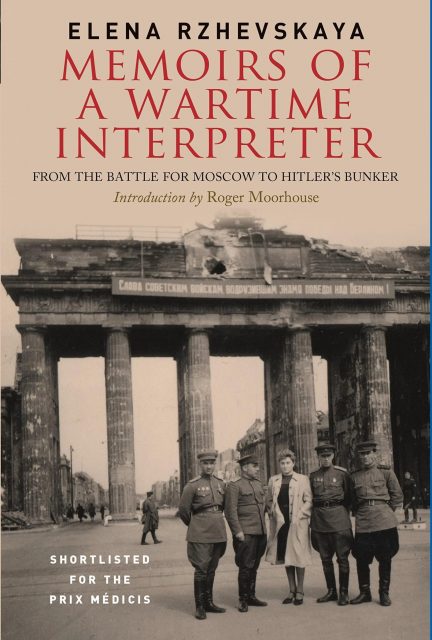

When the war ended, Elena would protest the lack of recognition for the heroes who defended Moscow in the battle at Rzhev by changing her name to Rzhevskaya.

When the Reich Chancellery was liberated, the 3rd Shock Army was sent in to the Füherbunker to find clues about Hitler’s whereabouts. They found his charred body and the body of Eva Braun outside and took them to Buch where autopsies were performed.

Because Hitler’s aids had burned their bodies after they died, their teeth became the most important way to identify the remains.

Hitler’s gold bridge and lower jaw were put in a box and given to Elena for safekeeping since she was considered the most reliable of the group.

The team then tracked down Hitler’s dentist, Dr. Hugo Blaschke; his assistant, Käthe Heusermann; and his dental technician, Fritz Echtmann. Heusermann was interviewed many times because of her familiarity with Hitler’s teeth.

Her description of Hitler’s teeth matched the autopsy report. Echtmann was able to identify the bridge he made for Hitler because it was one-of-a-kind.

The team then found one of Hitler’s bodyguards, Harry Mengershausen. He was able to describe the way they had burned the corpses and show the exact location where they had been buried.

Elena was certain that the world would know that Hitler’s body had been found within a few days. But Stalin forbid anyone to discuss it.

It was considered a state secret punishable with up to 15 years in the gulag for revealing it. Even Marshal Georgy Zhukov who accepted Germany’s surrender had no idea Hitler’s body had been found until Elena published a book containing details about her experience in 1965. In fact, Stalin had continued to pressure Zhukov to find Hitler.

In 1954, the year after Stalin died, Elena took her memoirs to the Znamya literary magazine. They published her work but edited out the part about Hitler’s death and the identification of his body.

They were afraid to be the first to release this information in case their was backlash from the government.

In 1961, Elena published a collection of her previously published novellas. She secretly included the story about Hitler in the collection and it was not discovered by the editors before going to print.

Heusermann and Echtmann were imprisoned for being witnesses to the discovery of Hitler’s remains. Heusermann wrote about her ordeal and described how she was imprisoned for six months before being placed in solitary confinement for six years.

She was then sent to a labor camp in Siberia until 1955 when she was finally freed as part of an agreement with Germany to release German prisoners.

After publication of her book Berlin, May 1945 Elena repeatedly traveled to Germany. When offered to meet Heusermann, she refused. “What could I say to her?” she writes. “I had been spared, but had evidently myself come within a whisker of her fate.” Heusermann had paid a terrible price for helping the Soviet investigation.

Another Article From Us: He Spent $660K on Nazi Memorabilia Then Gave it Away

In Memoirs of a Wartime Interpreter where she first included Heusermann’s story, Elena writes: “That burden of guilt will never leave me.”