In 90 days, seventy-five years after the world first witnessed the devastation caused by nuclear weapons, they will be illegal, according to international law.

From the end of World War II, the global community has been working to ban nuclear weapons. On the 24th October 2020, the 50th nation, Honduras, ratified the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, paving the way for these weapons to be declared illegal.

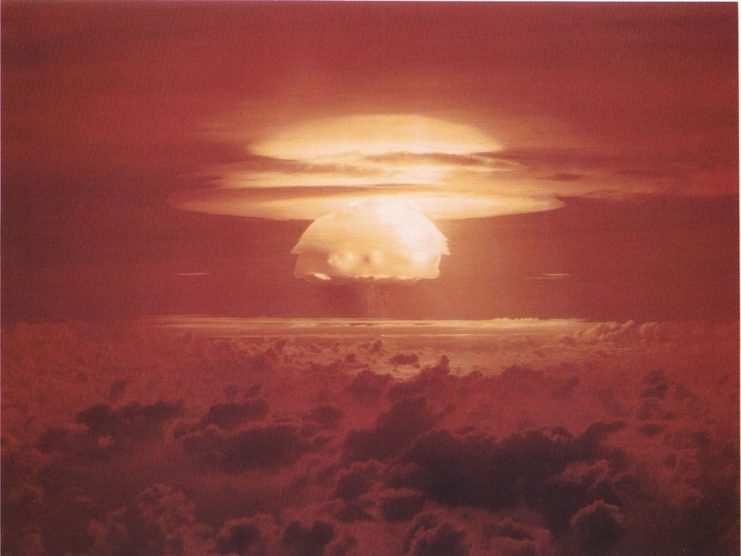

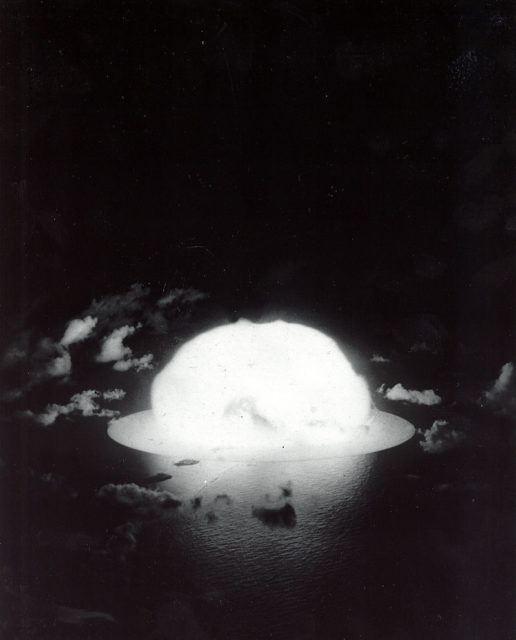

For people living across the Pacific, this is a long-awaited decision, as the second half of the 20th Century saw 315 nuclear tests conducted on land or in the waters around the Marshall Islands, French Polynesia, Australia, and Kiribati.

These tests were conducted by the French, English, and Americans, and the legacy left behind is not only harmful physical scars but also psychological and political scars.

The survivors of these tests have long raised their voices in resistance to nuclear testing and nuclear weapons. The formulation of a nuclear ban was spearheaded by the survivors of the devastating bombs dropped on Japan at the end of World War II alongside the Pacific-area residents who had long lived under the fall-out from nuclear testing.

The nations that adopted the treaty early were all based in the Pacific. Palau, Samoa, Kiribati, Fiji, Tuvalu, Vanuatu, Nauru, and New Zealand have all ratified the treaty, while the Cook Islands and Niue have acceded.

Of all the nations in this part of the world, Australia was notable by its absence. This is thought to be due to the close ties with the United States with its outdated reliance on nuclear deterrents.

It is not surprising that the original five nuclear nations, France, England, China, Russia, and the US, are vehemently opposed to the law. They have written to the treaty signatories suggesting that the treaty is a strategic error and asking them to rescind their ratifications to prevent the international law coming into effect.

The new law does not only ban the testing, use, or threat of use of nuclear weapons; it also includes obligations by those nations that tested these weapons. These obligations include assistance to victims of tests and rehabilitation of natural areas affected by the tests. The aid to victims includes medical care as well as psychological support.

The treaty will not permit those nations that undertook testing to abrogate their responsibility to the area or its peoples. Unfortunately, the countries responsible for the testing are not keen to release information about the tests.

The only way for the people of the Pacific to get the justice and assistance they deserve is if the testing nations tell the truth about the testing carried out. The testing countries must be held accountable for what happened, and they must be transparent in their dealings with the affected nations. Studies must be conducted to evaluate the effect these tests have had on the region’s people and natural resources.

Another Article From Us: Incredible Heroic Story of Grit & Determination of the 82nd AB

Nuclear justice for the Pacific is long overdue, but we can only hope that it is not far off with the new international law.