One of the casualties of World War II that gets less attention than the human plight it created is the theft of many important works of art stolen by the Nazis.

As they plundered their way across Europe, the Germans took over homes, often those belonging to Jewish families, and looted their possessions while the families themselves were shipped off to concentration camps.

Paintings, sculptures and other works were often given to high-ranking Nazi officials to keep, and many of the objects never made it back to the rightful owners at the end of the war.

Some languished in storage, while others were passed from owner to owner until tracing the original owners became an almost impossible task.

But in recent years, a movement has grown to ensure that these works are, if at all possible, returned to the families who owned them during the war–if not the actual person, then that individual’s heirs. If no family members survived, at the very least the artwork’s country of origin is given back the artwork to display in its museums and galleries.

Sometimes folks don’t even know that the painting they cherish is actually an ill-gotten gain stolen during the war. That was the case with David and Gabby Tracy, of Ridgefield, Connecticut, who recently discovered that a painting they had long prized had in fact been stolen, and rightfully belonged to Ukraine.

When David Tracy bought a home in Ridgefield in 1987, the painting The Secret Departure of Ivan the Terrible Before the Oprichnina, by Mikail N. Panin, came right along with the purchase price. (“Oprichina” means “repression” in English.)

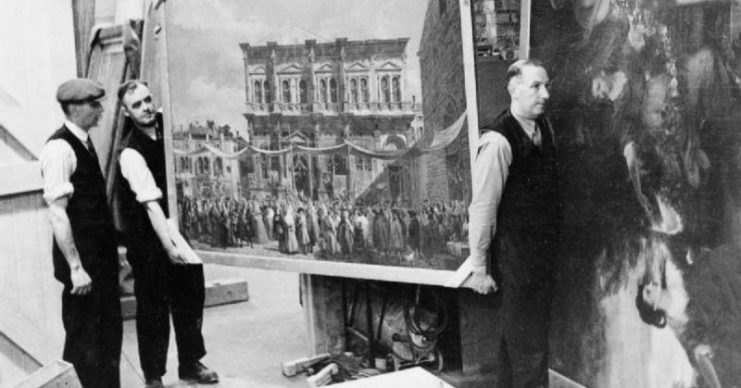

The couple enjoyed the work so much that later, when they bought a new home, they had a room especially constructed to accommodate its massive, 64-square-foot canvas.

The couple never imagined that the painting had a dark past. When they decided to downsize and move to a smaller home in Maine, they also decided to sell the artwork.

It had once been appraised at about $5,000 (U.S.), and they thought that would be a nice addition to their retirement fund. Fortunately, before it was sold at auction, a researcher in Virginia began looking into its history to see what he could discover about its origins.

When he found an illustration of the painting in a Russian publication, he contacted a museum in Ukraine. After discovering the painting was potentially looted artwork, he asked the auction house to hold off selling it, which it naturally did. The auction house then contacted the Federal Bureau of Investigation, which handles such matters.

The researcher was correct–the painting had been taken from a museum in Ukraine during the years it was occupied by the Germans.

The Tracys were stunned by the news, particularly because Gabby, now in her 80s, is a Holocaust survivor. She recently said in an interview that hearing the news of the painting’s true origins was “such a big shock to me.”

Experts believe the painting arrived in America with a Swiss man who emigrated there in 1946. He moved to Ridgefield, and when he died, there were no relatives to whom he could leave the artwork. Consequently, it stayed in the house, and the Tracys acquired it when David purchased the house.

The couple was anxious to see it returned to its home country, and Ukrainian officials said that they were thrilled with the Tracys’ cooperation.

In a statement last year, representatives of the Ukrainian embassy noted how grateful they were that the painting would be going home to a museum, and thanked the couple. “This is a perfect example,” its statement read, “where good will and art help to build bridges between nations.”

As for Gabby Tracy, she is relieved that the painting is being returned: “I’m happy it’s going back where it belongs.”