B Company of the U.S. Army’s 761st Tank Battalion closed in on the French town of Morville-lès-Vic on the morning of November 9, 1944. It was supposed to be an easy ride for the “Black Panthers,” the first all-black segregated tank company. Instead, it turned into an inferno.

Company Commander Captain John D. Long said after the event that he expected to be killed, “but I swore to myself there would never be a headline saying my men and I chickened [out].” As they rolled on to meet the SS 11th and 13th Panzer Divisions, his men were not about to let him down.

Just two and a half miles (4 km) to the east was the town of Marsal, where the Germans had established an Artillery Officer Candidate School. This school joined in defense of the town, raining shells on the advancing column of American tanks.

The weather was also against the Black Panthers as snow began to fall and settle, making the dark outline of the tanks even more visible while hiding the German bazooka positions.

Tank Commander Sergeant Roy King took a direct hit from a Panzerfaust at a crucial intersection and was shot dead as he made his escape from the blazing vehicle. There was anti-tank and machine-gun fire coming from all directions. Two of King’s crew members were wounded in the attack, but they did not back away from the fight.

Private John McNeil was able to use his sub-machine gun to good effect, holding off the Germans while his fellow crew member, technician James T. Whitby, went back into the burning tank and began firing the 30mm machine gun. The two men stayed at their post for another three hours, knocking out an enemy machine-gun post and German firing positions in second story windows.

At the end of the day the German occupiers were routed from the town. One prisoner was recorded as saying he had not come up against such bravery since he had been at the Eastern front. One American officer and nine enlisted men lay dead in the snow, but the town had been taken.

“After Morville-lès-Vic there wasn’t a white outfit that wasn’t damned glad to have us,” said Captain John D. Long, who would go on to pick up the nickname “The Black Patton.”

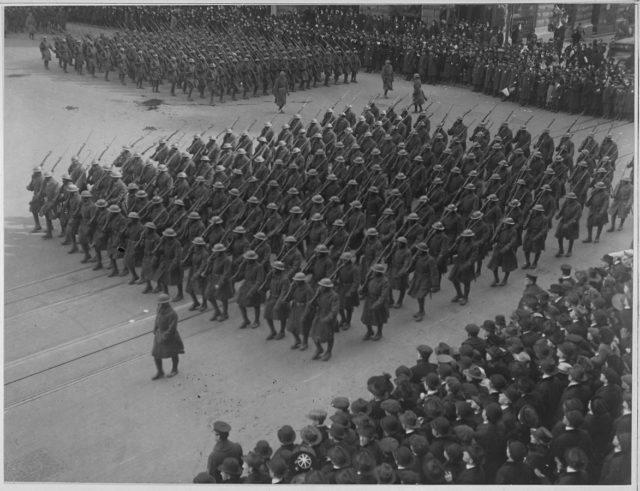

It hadn’t always been so. Before the war, African Americans were not thought to be up to the challenges of mechanized warfare. That all changed after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, and segregated air force units and tank commands were established.

In June 1942 Life magazine ran the headline “All they want now is a fair chance to fight,” while reporting on the first black soldiers training for tank warfare.

Between late 1944 and May 1945, the 761st was engaged in continual combat for 183 days straight. During five days of fighting in the bitter cold at the Battle of the Bulge, Staff Sergeant Frank Cochrane radioed a message back to headquarters from inside his tank. “They’ve hit me three times,” he said, “but I’m still giving them hell!”

On January 9, 1945 they pushed the German’s 13th Panzer Division back down the main supply route that had been used by the enemy to bombard the U.S. 101st Airborne at Bastogne. They then blasted a hole through the Seigfried Line in March.

By the end of the war, the Black Panthers had fought their way further east than any other U.S. fighting unit, playing a key role in the Battle of the Bulge and crossing the Rhine. They liberated Gunskirchen, which was a sub-camp of the Mauthausen concentration camp system. Members of the 761st received 391 individual decorations for heroism.

Their fighting record helped give President Harry Truman the impetus to push through the desegregation of U.S. fighting forces in 1948. But it was not until 1978 that President Jimmy Carter would honor the 761st with an official Presidential Unit Citation, recognizing the Black Panthers’ contribution to winning the war in Europe.