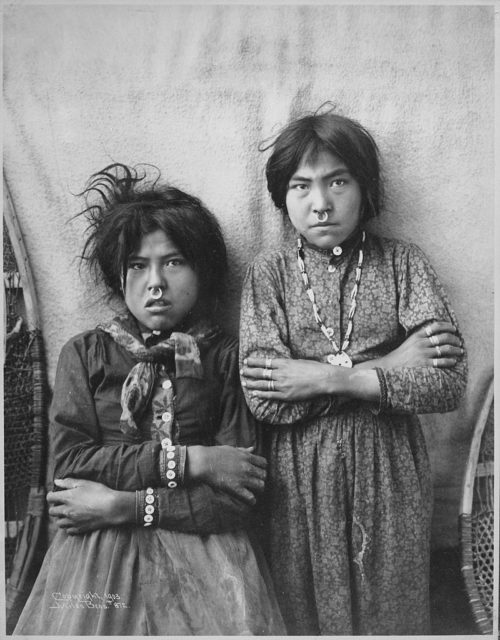

In the early 1900’s Russian traders trying to gain a foothold in Alaska clashed with the indigenous peoples that had lived there for thousands of years. The Tlingit and Haida peoples had learned to live in this inhospitable environment. With the expansion of the Russian trading enterprise, conflict was inevitable.

The Russian traders had already clashed with the Aleut as they hunted fur seals and sea otters, as these pelts carried a premium price in the fur trade. Toward the end of the 17th Century, Tsar Paul I granted The Russian American Company a monopoly license to exploit Alaska’s east coast’s fur trade. In 1799 the Russian traders arrived in the territory belonging to the Tlingit people.

The Russian American Company decided that a location on the Bay of Alaska would suit their trading post. They met with resistance from the Tlingit community, who valued their independence. In 1802, a clan of the Tlingit people, the Kiks.ádi, launched an attack on the Russian trading post named Redoubt Saint Michael. Situated neat Sitka. The clan was victorious and slaughtered nearly all the Russians and Aleut people living in the outpost.

The clan’s shaman predicted that the Russians would retaliate against the clan and that the Russians would be led by Alexander Baranov. To defend their territory, the Kiks.ádi built a fort. They withstood the initial assault, but after six days of bombardment and food running low, the clan’s elders decided to withdraw and undertake a march to the north to protect the clan members. The Russians took this as a victory, established a fortified presence in Sitka, and declared Alaska as a Russian colony. In 1867, the Russians sold Alaska to the Americans for $7 million.

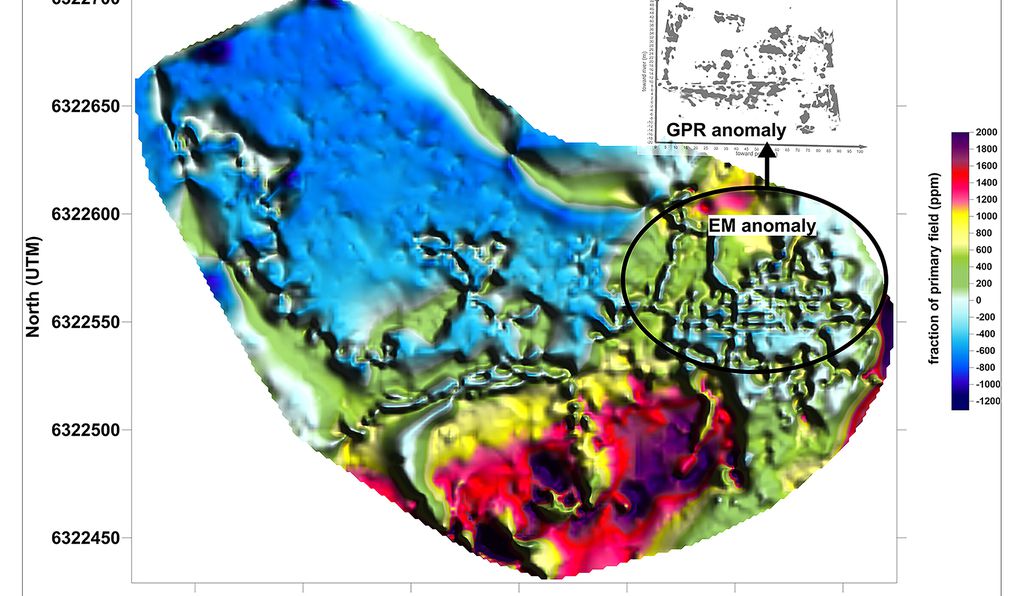

To commemorate the battle, authorities declared the area part of the Sitka National Park, but the exact location of the Kiks.ádi fort had remained a mystery. Almost 200 years later, archaeologists have pinpointed the fort’s site using electromagnetic instrumentation and ground-penetrating radar.

Baranof Island, where the fort was located, has been an archaeological study site for a long time and, since 1910, has enjoyed federal protection by the American Government. When the Russians destroyed the fort, they documented where it was. The US National Parks Service (NPS) had indicated a specific clearing as the fort’s probable site, but this was not confirmed.

Thomas Urban, a research scientist from Cornell University, in association with Brinnen Carter of the NPS, published the account in the archaeological magazine Antiquity. He said that there had been several investigations into the fort’s location, all of which produced clues to its location but no definitive place. The heavy forestation of the island made any study a tedious and challenging task.

Urban was in Sitka on another project when the NPS asked if he would be interested in locating the fort. Investigating past searches, he found that in the 1950s, trenches were dug, and some pieces of rotting wood were found that could have come from the fort. Cannonballs and other artifacts that indicate this could be the battle site were found by the NPS between 2005 and 2008. All of this was circumstantial evidence and did not definitely prove the location of the fort.

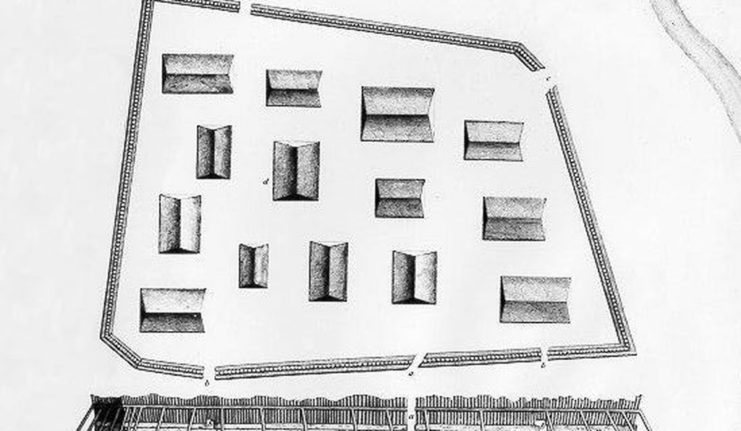

In the summer of 2019, Carter and Urban scanned large areas of the park with Geophysical tools, and they located the footprint of the fort. Trapezoidal in shape, 300 feet long and 165 feet wide, the perimeter surrounds the clearing the NPS had designated.

The design of the fort, named Shís’gi Noow, is unique in Tlingit history and seems to have been built specifically to repel the colonizers. Translated into English, the fort’s name is sapling fort, again a change from the norm. It seems the Tlingit people learned that the young trees would provide some protection against cannonballs as they would absorb the impact better.

A dean at the University of Alaska Southeast, Thomas Thornton, an authority on Tlingit history, has collected oral history from the Tlingit people. Part of the oral history compiled was an account of the survival march undertaken by the Kiks.ádi. An elder of the clan, Herb Hope, spent a great deal of time in the 1980s and 1990s trying to retrace this march’s route. He was determined to show that this was not a retreat but survival.

Speaking at a Tlingit Conference held in 1993, he said that their ancestors followed a coastal path and that the march was from the fort to a planned location. He emphasized that at that time, the Russian traders, with their support, could not suppress the Tlingit people.

The oral history of the Tlingit tells us that around 900 people took part in this march. They moved from one camp to the next as they marched north along Baranof Island until they reached Chichagof Island, where they inhabited a deserted fort called Chaatlk’aanoow. This fort gave them the ability to blockade the Sitka Sound, which complicated the Russian fur trade.

When American traders learned of the Tlingit move and their blockade, they quickly moved in to exploit the Russian difficulties. They established a trading post on Catherine Island, close to the Tlingit fort. People from all over Southeast Alaska came to trade with the Americans at this post. Today, this bay is still known as Traders Bay.

The Tlingit people returned to Sitka in 1821 but would never regain sovereignty over their land.

Another Article From Us: Iconic American Colt Firearms Now Owned by a Czech Company

The NPS has no plans for further investigation of the site.