The Volkswagen Beetle is an iconic reminder of the skill and ingenuity of German engineering and stands out as a seminal vehicle in the history of the automobile.

A car that has become a cultural signifier from a company that has built upon a reputation for innovation and excellence since the end of the war.

However, the story might have been completely different had it not been for British Army officer Ivan Hirst.

The company was in pieces in the summer of 1945 with much of its manufacturing supply chain and production capacity wrecked by the fierce fighting that finally brought down the Nazi regime.

Once the dust had begun to settle the remaining industrial assets across Germany were taken and divided up between the Allies, the USA, Britain, France and the Soviet Union.

The Potsdam Agreement allowed for factories to be dismantled and machinery repatriated under the terms of war reparations.

The Volkswagen Beetle factory in Wolfsburg was handed over to the British by the Americans. The British handed the reins to a twenty-nine-year-old Major who had trained to be an optician before the war and was now a civilian Military Governor.

Ivan Hirst was not dismayed by his new role. He had come from a family of Northern industrialists; his father and grandfather had built modern factories near Manchester and their clocks and optical instruments had been exported around the world.

Following the Allied invasion of Normandy, in September 1944 Major Ivan Hirst found himself in charge of a tank repair plant in the Belgian town of Lot, South West of Brussels.

Within four weeks the plant was turning out twenty-five repaired armoured vehicles, ready to go, some with a new coat of paint.

He was managing a workforce six-hundred strong including local Belgian men and British welding crews, responsible for their accommodation, food and welfare.

The repair work was often hampered by a lack of spare parts and many times these had to be either improvised or made from scratch.

By the time he arrived in Wolfsburg in August 1945 Hirst was well versed in the problems associated with setting up a production line and in dealing with a diverse workforce.

The town was under-populated and resembled a building site but was home to refugees and former forced laborers from all across Europe.

The factory was being used by the Royal Engineers as a repair shop, one for engines and one for spare parts employing up to eight per cent of the workforce.

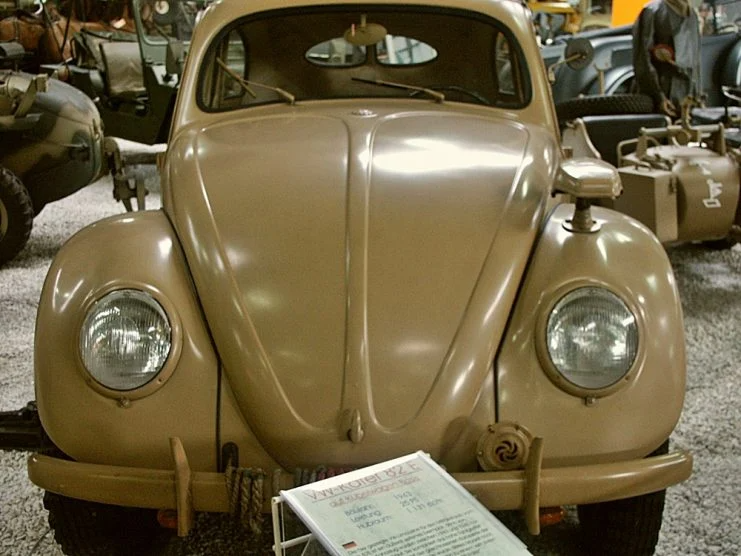

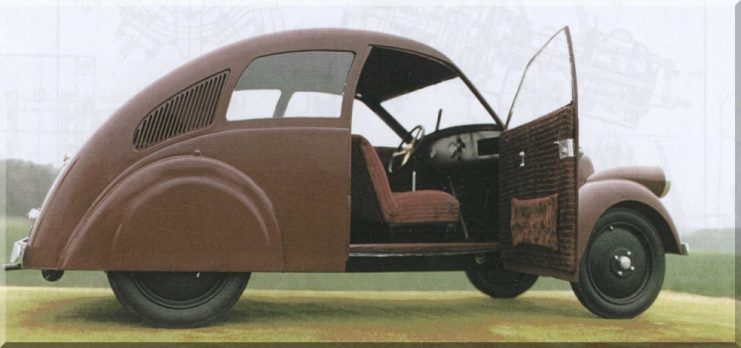

The Volkswagen plant had been used by the Americans to produce Kübelwagens, or tub-trucks as they were known, and the machinery earmarked for export to the UK or Australia. There was little or no commercial interest in producing the Beetle.

British car maker Sir William Rootes told Hirst he expected car production to fail inside two years with the observation that the vehicle, “…is quite unattractive to the average motorcar buyer, is too ugly and too noisy…”

When the British offered the plant to US company Ford, Henry Ford II, son of the founder Edsel Ford, visited with the Chairman of the Board, Ernest Breech who said, “Mr. Ford, I don’t think what we’re being offered here is worth a dime.”

Undeterred, Hirst set out to prove the naysayers wrong. By the end of 1946 the plant was producing 1,000 vehicles a month for local occupying forces and by 1947 began exporting, first to the Netherlands, then all across Europe.

In 1948 he recruited German assistant Heinz Nordhoff, who had run factories for German car manufacturer Opel.

Hirst left Volkswagen in 1949 as a going concern for a career with the Foreign Office based in Paris, where he remained until his retirement in 1975. He died in 2000.

When the 101st Airborne Saved Friend and Foe

Since the war the Volkswagen Beetle has sold more than 21 million units across the world, becoming the most-built motor vehicle in history.