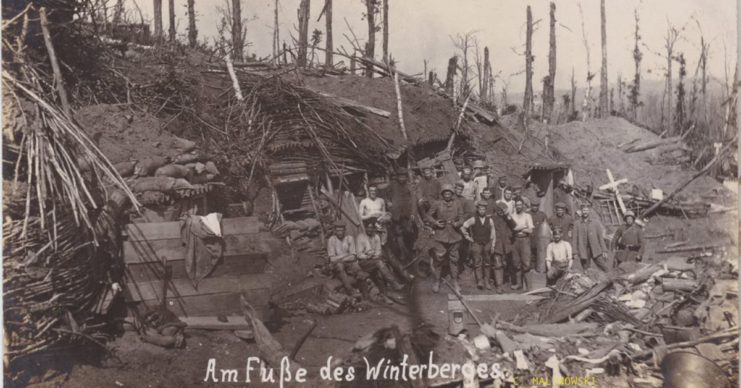

War is an ugly business. The only redeeming reality for soldiers on the ground caught in fierce fighting is that, often, their deaths are mercifully quick. Alas, that was not the reality for 270 German soldiers during World War I, who were fighting near the town of Craonne in Northern France and resting near the outside of the Winterberg Tunnel. Down below, inside the tunnel, munitions for the battle lay protected, or so the soldiers thought.

Then, on May 4th, 1917, the unthinkable occurred.

Winterberg Tunnel bombed

The area was shelled by French forces, and the tunnel — and its contents — were destroyed, then sealed, trapping almost 300 fighting soldiers from Germany’s 111st Reserve Infantry in the process. The tunnel’s collapse produced, in essence, a tomb with men who were still alive but with only enough oxygen for six days. By the time their ordeal was over, only three men were retrieved from the rubble still breathing and begging for water.

The war was not going well for Germany, and their forces soon retreated from the region, leaving the dead men behind.

Once the war was over in 1918, the 270 bodies were simply forgotten, ignored, or both.

Now, however, thanks to the efforts of a father-and-son team of historians, the bodies have been uncovered, 4 meters below the surface. The men, Alain and Pierre Malinowski, risked charges from the police for disturbing the remains, but they followed through on their commitment to uncovering the soldiers, saying that they hoped the soldiers’ families can be contacted and the remains returned home.

Today, the area is popular with dog walkers and others just out for a hike or a stroll. In all probability, few knew what lay beneath the ground they walked over every day.

The tunnel is about 1,000 feet in length, and it lies beneath the Chemin des Dames, or Ladies’ Path. It sits not too far from the city of Reims.

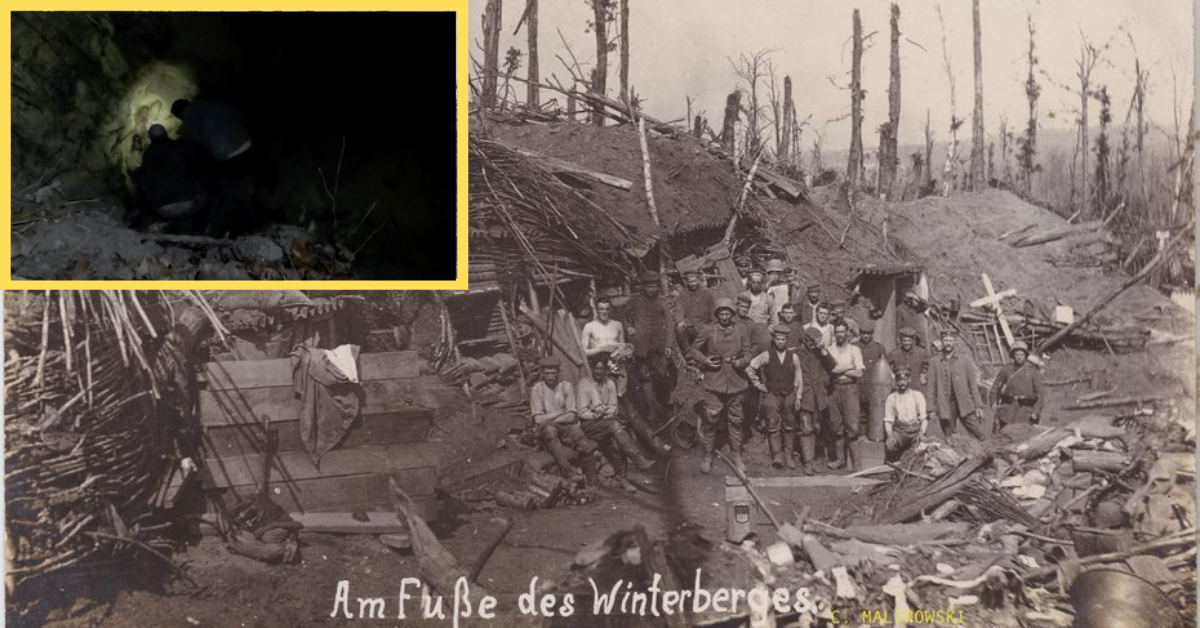

Malinowski and his father excavated the tunnel

Malinowski told the BBC that he excavated the site and took photographs, but left the bodies undisturbed. As he explained, he thinks France has a “moral duty” to authorize a full excavation and return the soldiers to their homes and families, if that is at all possible. They died in a way “we cannot begin to comprehend,” he added, and just because they were not French citizens does not mean they shouldn’t be treated with the respect and honor afforded all veterans.

Both the French government and German officials are (at the time of this writing) undecided about how to proceed. Some argue the tunnel should be a memorial, while others support a full excavation and repatriation of the bodies back to Germany.

However, what happens next is still uncertain.

Although the tunnel is horrific in some ways, it is not a rare find in a country where many battles of two world wars were waged. There are places in France, particularly in rural regions, where there are still shells and unexploded bombs not far below ground.

According to reports of the BBC, looters have already tried to dive into the site, though accessing the tunnel itself has, so far, proved impossible. It will take heavy equipment, managed by archaeologists, to get down to where the men lay. But time is of the essence, because if there is a way for the site to be raided illegally for war memorabilia, no doubt thieves will find it.