Glenn Gallagher was fishing for prawns in his boat, The Two Boys, just days before Christmas 2018 when he felt something heavier than normal in his nets.

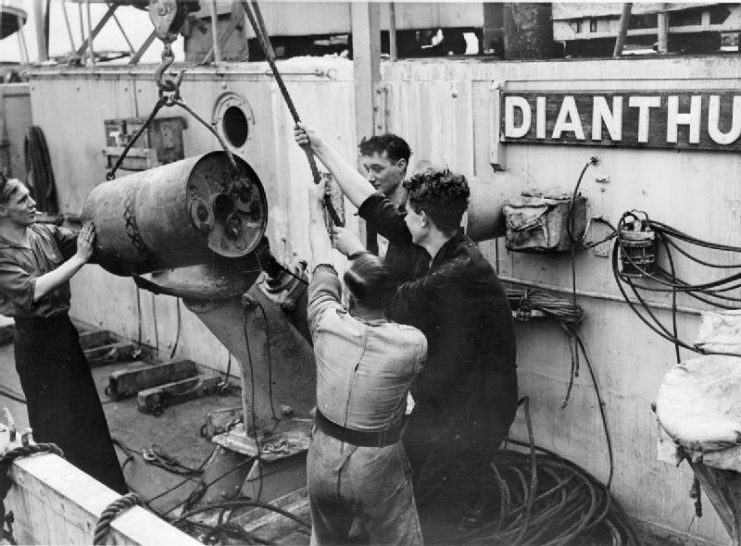

Together with his colleague, crew-man Ross Dunn, they hauled on board what looked like an old boiler tank. Then the unmistakable smell of ammonia and old paint told them that this was something much more dangerous.

“The smell of explosives was horrific,” said Gallagher, “I am just glad it never went off on us to be honest.”

The Belfast Coastguard, coordinating with the Royal Navy, told the fishing boat to rendezvous with a ship just north of Great Cumbrae where the unexpected catch was transferred to a dive team.

Divers from the Northern Diving Group (NDG), based at HM Naval Base Clyde, examined the item. It was positively identified as a Mark 7 WWII depth charge.

The Coastguard put out repeating broadcasts to warn shipping of the hazard and to alert them to the disposal procedures that were to follow.

WWII ordnance is not an entirely unusual catch in this area as there was a munitions dump close by in the Clyde Estuary during the war.

On the 20th December, the dive team took the bomb a mile out to sea to an area of deep water where they removed it to the sea-bed at a depth of 27 meters.

The Royal Navy emergency response team put a 700-meter exclusion zone around the area before the divers placed explosive charges next to the bomb and carried out a controlled explosion.

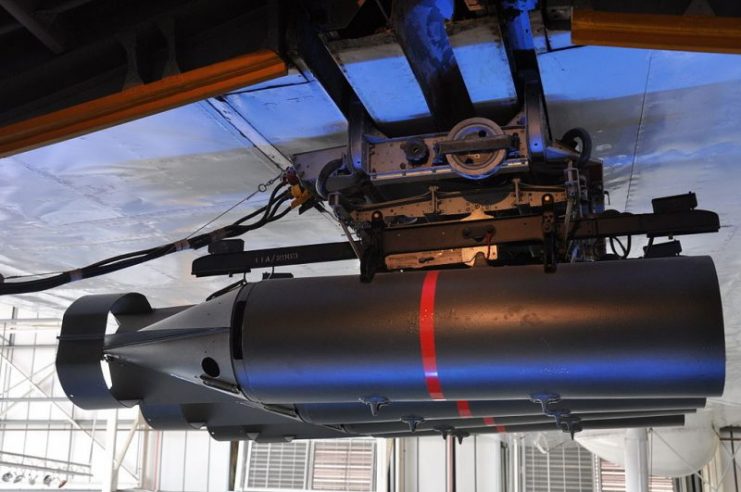

The Royal Navy Type D Depth Charge was designated the Mark 7 in 1939. With an initial sinking speed of just over 2 m/s (7 ft/s), it could reach 3 m/s (9.9 ft/s) by 75 meters. It was primarily designed for anti-submarine warfare.

By 1940, the Navy was attaching 150lb weights to almost double the sinking speed with a maximum detonation depth of 270m (900ft).

The Mark 7’s 290lb payload was designed to split a submarine’s 22mm steel hull at a distance of 20 feet, and at 40 feet the detonation was expected to force a submarine to the surface.

The science around depth charge deployment is based on the use of serial shockwaves in order to produce the most damaging effects.

During the Battle of the Atlantic, British and Commonwealth vessels became adept at locating and destroying German U-Boats and developed the first submarine hunter-killer strategic groups.

Depth charges were usually launched in pairs and timed to detonate at different depths so that shockwaves could be set up to act from opposing directions on the enemy craft.

The initial shockwave produced by the explosive material was expected to cause damage to personnel and equipment.

The secondary shockwave, resulting from cyclical expansion and contraction of the gas bubble produced by the bomb, would bend the submarine back and forth.

This second shockwave was the one most likely to cause a hull breach, especially if there was another depth charge close by.

Largs, the hometown of prawn fisherman Mr. Gallagher, was used as a flying boat reception facility during World War Two and played an active supporting role in the Battle of the Atlantic.

Consolidated PBY Catalinas flew from Largs where they were serviced and fitted out with specialist equipment used in the search for German U-Boats.

While the slipway remains, the airfield where the seaplanes were serviced is now a putting green.

During WWII, Catalina seaplanes were credited with destroying 40 enemy submarines by dropping depth charges like the one discovered by Mr. Gallagher.