During World War II, the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) constructed several notable warships, among which the IJN Shinano stands out. Initially intended to be a Yamato-class battleship, strategic shifts following the Japanese fleet’s defeats at the Battle of Midway resulted in her transformation into an aircraft carrier.

Shinano is historically important as she is the largest warship ever sunk by a submarine.

Construction of the IJN Shinano

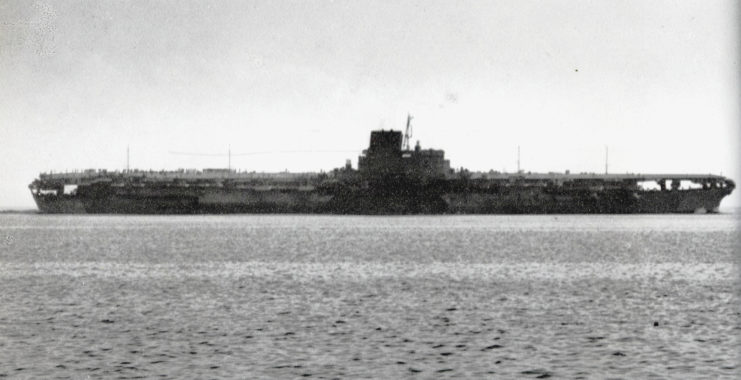

Construction of the IJN Shinano began on May 4, 1940, at the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal and progressed smoothly until 1942. However, that year, a series of strategic defeats by the Americans necessitated her conversion from a battleship to an aircraft carrier. Rather than becoming a fleet carrier, Shinano was reconfigured as a heavily-armored support carrier with a displacement of 65,800 tons, primarily designed to store reserve aircraft and fuel.

Shinano‘s construction was conducted under a veil of secrecy, with a high fence erected around the site to prevent any public visibility. Workers were bound by strict confidentiality agreements, with severe penalties, including execution, for any breaches.

As a result, Shinano stands as the only major warship of the 20th century with no known construction photographs. Even after completion, it was only captured on film twice: once by a Boeing B-29 Superfortress during a reconnaissance mission and once by a civilian during sea trials.

Armor and armament

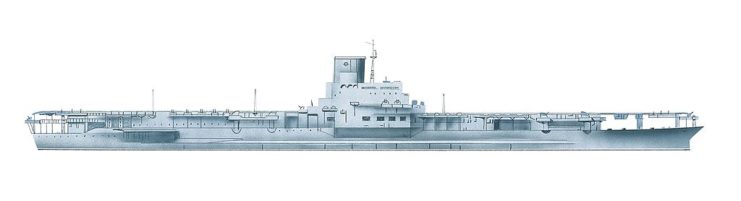

The IJN Shinano was based on the design of the Yamato and Musashi. Initially, she was meant to have slightly thinner armor, reduced by 10-20 mm, and newer anti-aircraft guns. However, these plans changed when she was converted into an aircraft carrier. This led to major changes from the Yamato-class, with Shinano losing much of her armor and large main guns.

As a carrier, Shinano adopted the flat top typical of her new role, featuring a streamlined flight deck. She was massive, measuring 872 feet long with a beam of 119 feet and a draft of almost 34 feet. Her propulsion system had 12 Kampon water boilers powering four steam turbines. This setup produced 150,000 shaft horsepower, giving Shinano a top speed of 27-28 knots in ideal conditions.

Shinano was designed to carry many aircraft and had strong defenses for her time. She was equipped with eight twin five-inch dual-purpose guns, 35 triple one-inch anti-aircraft guns, and twelve 28-barrel 4.7-inch anti-aircraft rocket launchers. Her waterline armor was between 160-400 mm thick, and her flight deck had 75 mm of armor.

Traveling toward certain destruction

Initially slated for commissioning in early 1945, the construction scheduled for the IJN Shinano was expedited following the Battle of the Philippine Sea. The engagement inflicted major losses on the Japanese Navy, including two fleet carriers, one light carrier and two oilers, with several smaller vessels sustaining damage.

The accelerated construction of Shinano resulted in compromised workmanship on later components. Despite this, she was launched on October 8, 1944, and commissioned on November 19 of the same year.

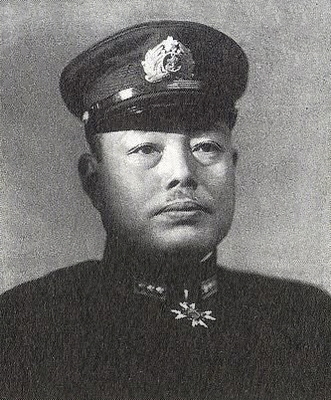

Following her commissioning, Shinano was scheduled to transit from her shipyard to Kure Naval Base, where she’d be armed and receive aircraft under the command of Capt. Toshio Abe. Despite pressure from superiors to depart immediately, Abe requested a delay, due to incomplete bailing pumps and fire mains. Unfortunately, his plea was denied, and he was forced to set sail at night, contrary to his preference for a daytime departure.

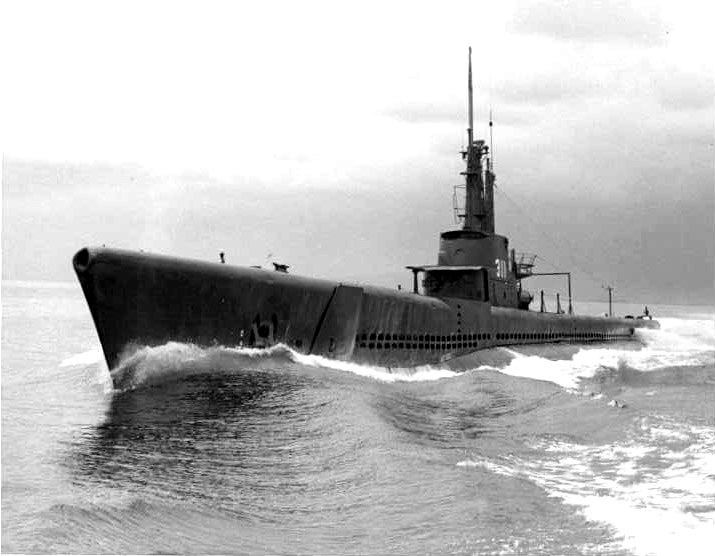

Leaving at 6:00 PM on November 28, 1944, Shinano was accompanied by Isokaze, Yukikaze and Hamakaze. While en route, the ships detected radar signals that indicated the presence of an American submarine nearby, prompting them to employ evasive maneuvers. Unbeknownst to the crew, these inadvertently placed Shinano directly in the path of the USS Archerfish (SS-311).

Sinking of the IJN Shinano

Joseph Enright, commanding the USS Archerfish, detected the IJN Shinano two hours before the aircraft carrier became aware of the submarine’s presence. Mistaking the vessel for part of an American wolfpack, Cmdr. Abe of the Japanese forces ordered his ships to change course to evade Archerfish. Despite Shinano‘s superior speed, she was required to slow down to avoid any likely damage.

At 2:56 AM on November 29, Abe initially steered toward the submarine, but then veered southwest, inadvertently exposing Shinano‘s entire flank to Archerfish. At 3:15 AM, Enright ordered the launch of six torpedoes, two of which struck their target before the submarine dove to a depth of 400 feet to avoid counterattack.

Shinano was hit by four torpedoes, leading to her sinking. Enright and his crew didn’t learn the carrier’s identity until the end of World War II and were unaware that it took over seven hours for the Japanese vessel to sink after being struck.

Hindsight is 20/20

Initially, those aboard the IJN Shinano underestimated the severity of the damage caused by the torpedo strikes, meaning minimal effort was made to salvage the ship. Abe, in particular, directed her to maintain maximum speed, inadvertently accelerating the flooding of the aircraft carrier.

Unfortunately, by the time they grasped the gravity of the situation, it was too late. The ship had become too heavy to be towed by escort vessels, too inundated to be pumped out and too irreparably damaged for the majority of her crew to evacuate. Out of her 2,400-man crew, 1,435 perished with the ship, including Abe and both navigators.

The survivors were sent to Mitsukejima until January of the subsequent year, preventing the widespread dissemination of news about Shinano‘s sinking. Following the conclusion of the war, the US Navy analyzed the aircraft carrier, along with other Yamato-class ships, and identified significant design flaws that rendered specific joints susceptible to leakage. It was concluded that the torpedoes from the USS Archerfish happened to strike these vulnerable joints, contributing to Shinano‘s demise.

Are you a fan of all things ships and submarines? If so, subscribe to our Daily Warships newsletter!

Regarding Enright, US Naval Intelligence initially doubted his claim of sinking a Japanese carrier, believing all had been identified. However, this was rectified after the war, and Enright was duly honored with the Navy Cross for his victorious achievement.