The Japanese surrender in World War II signaled the conclusion of one of the most harrowing and destructive periods in human history. Although Germany capitulated in May 1945, it took Japan several additional months to admit its defeat. While many argue that the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were the primary reasons for the country’s capitulation, the reality is that a variety of factors influenced this decision.

Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Two key events that led to Japan’s surrender were the atomic bombings on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. On the morning of August 6, 1945, the former was subjected to an attack that decimated the city and inflicted a devastating human toll, with between 90,000-146,000 killed both during Little Boy‘s detonation and after, due to the effects of radiation exposure and burns to the skin.

Just three days later, on August 9, Nagasaki experienced a similar fate, with the Boeing B-29 Superfortress Bockscar dropping the atomic bomb Fat Man on the city, located some 261 miles from Hiroshima. Just like the latter, Nagasaki suffered extensive losses, with between 60,000-80,000 citizens perishing within four months of the attack.

Between both detonations, it’s estimated around 129,000-226,000 people lost their lives – a truly devastating number.

The atomic bombs not only demonstrated the US military’s superiority, but also signalled the emergence of a new and terrifying era in warfare. The realization that further nuclear attacks could obliterate Japanese cities forced leadership to reconsider their position; the fear of additional devastation, coupled with the understanding that conventional defenses were futile against such power, significantly influenced Japan’s decision to surrender.

Declaration of war by the Soviet Union

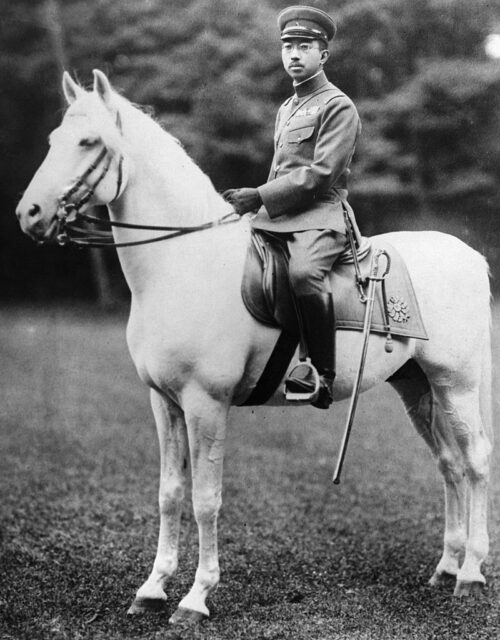

Adding to the devastation of the atomic bombings was the Soviet Union’s declaration of war on Japan on August 8, 1945. This was a crushing blow to the Japanese military’s already dwindling hopes. Japanese officials had underestimated the threat posed by the Red Army, believing they wouldn’t have to confront Soviet forces until spring 1946. Emperor Hirohito had even sought Joseph Stalin’s help as a mediator between Japan and the United States.

The sudden Soviet invasion of Manchuria caught Japan off guard, with 650 of the 850 occupying troops killed or wounded in the first two days of fighting. This unexpected assault shattered any remaining hope for a negotiated peace and underscored Japan’s deepening geopolitical isolation.

Facing the grim reality of a two-front war, Japanese political and military leaders realized their situation was untenable, and even Emperor Hirohito urged officials to reconsider surrender.

Japan’s military resources were beginning to dwindle

By 1945, Japan found itself in an increasingly untenable position. Years of sustained conflict had severely diminished its military capabilities, with the United States particularly to blame. The country’s strategic island-hopping campaign had effectively isolated Japan, severing its connections to occupied territories in the Pacific. This isolation was compounded by a stringent naval blockade and a relentless aerial bombing campaign that targeted Japanese cities and industrial centers, crippling the nation’s war effort.

The scarcity of vital resources caused by this led to widespread suffering and hardship among the Japanese populace. Food and fuel shortages became acute, with the average civilian’s caloric intake dropping to an unhealthy 1,680 per day. There was also a shortage in working-age males, given the majority of those able to fight had been recruited into the military.

The realization that the war was unwinnable, given the dire state of the nation’s military and resources, became a key factor in leadership’s decision to surrender.

Japan wanted to preserve its Emperor system

A unique feature of Japan’s surrender negotiations was the emphasis on preserving the emperor system; the government maintained this position as a non-negotiable condition. The anxiety that unconditional surrender might result in the abolition of the monarchy was a major concern that shaped the decision-making at the highest levels.

The outcome of these discussions was the “Humanity Declaration,” in which Hirohito consented to a “Symbolic” emperor system. This arrangement involved a rejection of the emperor’s divinity and instead established him as “the symbol of the State and of the unity of the people.”

In essence, although the emperor would remain a figurehead, he would no longer wield the primary political authority. Instead, a new constitution would be enacted.

Facilitating Japan’s surrender

The process of facilitating Japan’s surrender was marked by significant diplomatic and communicative efforts. Behind the scenes, diplomats and intermediaries worked tirelessly to establish a channel of communication between Japan and the Allied forces. These efforts were aimed at finding a mutually acceptable solution that would allow the country to surrender while addressing the concerns of all parties involved.

With all the aforementioned factors piling on top of the each other, the decision was ultimately made for Japan to surrender, with Emperor Hirohito announcing the news to the public via a radio broadcast on August 15, 1945.

The first time he’d spoken to average citizens directly, the emperor explained, “The war has lasted for nearly four years. Despite the best that has been done by everyone – the gallant fighting of the military and naval forces, the diligence and assiduity of our servants of the state, and the devoted service of our one hundred million people – the war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan’s advantage, while the general trends of the world have turned against her interest.”

More from us: Paul Tibbets Dropped the Atomic Bomb on Hiroshima and Was Given No Funeral or Gravestone

Want War History Online‘s content sent directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter here!

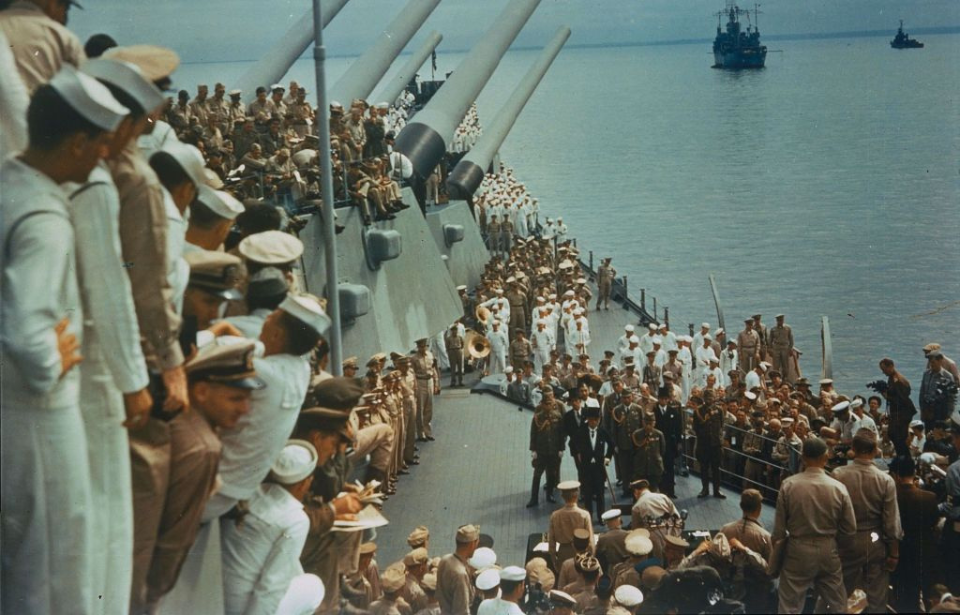

Just over two weeks later, aboard the American battleship USS Missouri (BB-63), the Japanese Instrument of Surrender was signed. Those present included representatives from the Empire of Japan and the Allied nations, with the most notable being Gen. Douglas MacArthur, Fleet Adm. Chester Nimitz and Chief of the Japanese Army General Staff Gen. Yoshijirō Umezu.