During wartime, it is nearly inevitable that people will push themselves to their limits, achieving acts of remarkable bravery and heroism. Individuals who accomplish such feats are typically celebrated. However, war also demands the testing and surpassing of other limits, often requiring individuals to face and overcome challenges far beyond ordinary imagination.

A prime example of this is George Ray Tweed, a radioman 1st class in the US Navy, who demonstrated extraordinary stealth and resilience by surviving and escaping the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) on Guam for two years and seven months.

Japanese invasion of Guam

George Ray Tweed had been in the US Navy for 16 years when Japan invaded Guam in December 1941. In fact, he’d lived on the island with his family since mid-1939. Family of service members stationed on Guam had already been evacuated, so when the Japanese launched their attack on December 8, the only ones on the island were sailors and US Marines, along with a few nurses.

The numerically superior Japanese quickly swamped any resistance on the part of the Americans, with the garrison surrendering on December 10. However, six sailors decided not to give in. Instead of resigning themselves to spending the rest of World War II in a Japanese prison camp, they chose to flee.

Four of them were stationed at the Radio Communications Center, including Tweed. The other two were crewmen from the USS Penguin (AM-33), a minesweeper that had been sunk by the enemy at the start of the invasion.

George Ray Tweed refused to surrender to the Japanese

Upon learning of the American surrender, George Ray Tweed and Radioman 1st Class Albert Tyson quickly fled. Before leaving town, Tweed stopped by his home to pack essentials into a pillowcase, a task Tyson also did. However, in their rush, they neglected to bring one of the most vital resources for survival: water. This oversight was especially dangerous given Guam’s lack of fresh water.

After trekking through the dense trees and getting cut from the island’s thick vegetation, the two eventually paused to rest. They were discovered by a native Chamorro named Francisco, who took them to his home and provided them with much-needed food and water.

Their rest was short, as the Japanese were already searching for the escaped Americans. Determined to help, Francisco went to great lengths to help Tweed and Tyson, guiding them to a safe hiding spot in the bush for the night and giving them another meal the next morning.

Helping the escaped Americans remain hidden

The local Chamorro people’s help proved to be a crucial factor in terms of George Ray Tweed’s evasion of the Japanese. Without their assistance, he probably would’ve been captured and executed.

Enemy troops initially tried to get the native islanders to assist in their efforts to capture the Americans by offering a monetary reward for information. This started out as ¥10 for each American, and ¥50 for Tweed, because of his skill for repairing radios. However, nobody helped; the Chamorros hated the Japanese and only cooperated with them when threatened.

Ramping up efforts to capture George Ray Tweed

After their first week of evading the Japanese, George Ray Tweed and Albert Tyson realized that efforts to catch them were being ramped up. They moved to a new, more remote hideout: an excavated dirt shelter dug by another local, Jesus Quitugua. Another Chamorro, Juan Cruz, managed to smuggle them an old radio, which Tweed managed to get working

Tweed and Tyson survived for a few months in their dugout shelter. Meanwhile, the Japanese upped the rewards for information to ¥100 per American and ¥1,000 for Tweed, but, still, nobody turned the men in.

By this point, the other four Americans had been hidden by a Chamorro named Miguel Aguon, and Cruz helped Tweed and Tyson meet up with them. When all six were together once more, they decided their best bet for long-term survival was to split up. Each went their own way and, from this point on, Tweed was on his own.

Splitting up wasn’t the best idea

Things didn’t go so well for the other Americans after this. Three were captured almost immediately and made to dig their own graves before being executed. Tyson and another man, Machinist Mate 1st Class C.B. Johnston, held out longer, but, eventually, the Japanese discovered them hiding in a chicken coop. They shot Johnston, and when Tyson came out with his hands up, they shot him, too.

Tweed was now the last one left alive, having hidden himself in a cave. However, the enemy was pulling out all the stops to locate him. He’d also been typing out a local Resistance newsletter on a small typewriter that one of the locals had smuggled to him.

With the help of another Chamorro man, Antonio Artero, Tweed found his new and final hideout on Guam: a hidden opening at the top of a high cliff overlooking the ocean, on the northern part of the island. This was where he stayed until his rescue.

George Ray Tweed was rescued after more than two years

During this time, Antonio Artero regularly brought George Ray Tweed food and water. The latter promised to repay him for his help one day, even though the Chamorro people refused to entertain the idea of payment. Meanwhile, the Japanese had taken to torturing and executing local islanders whom they believed were withholding information about Tweed. Even in the face of such atrocities, nobody gave him up.

Tweed continued to hold out as the weeks, months and years passed. Finally, on June 11, 1944, he saw American aircraft flying over Guam. A month later, on July 10, ships got close enough for him to signal. However, instead of begging for his own rescue, he flashed them a coded message, warning them of the location of Japanese gun batteries on the island.

Only after they had acknowledged receiving this information did he ask for help.

What happened after World War II?

George Ray Tweed was rescued on July 10, 1944. He received the Legion of Merit with “V” device and the Silver Star. Following the Second World War, he not only returned to Guam to thank the locals who’d helped him, he also fulfilled his promise to Antonio Artero. The man had mentioned a dream of owning a brand new Chevrolet – and that’s exactly what Tweed gifted him.

More from us: Operation Catechism: Demise of the German Battleship Tirpitz

Want to become a trivia master? Sign up for our War History Fact of the Day newsletter!

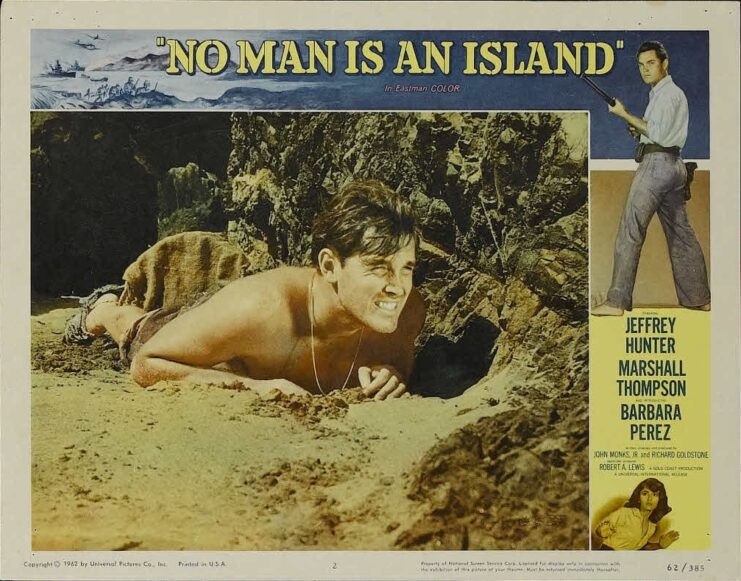

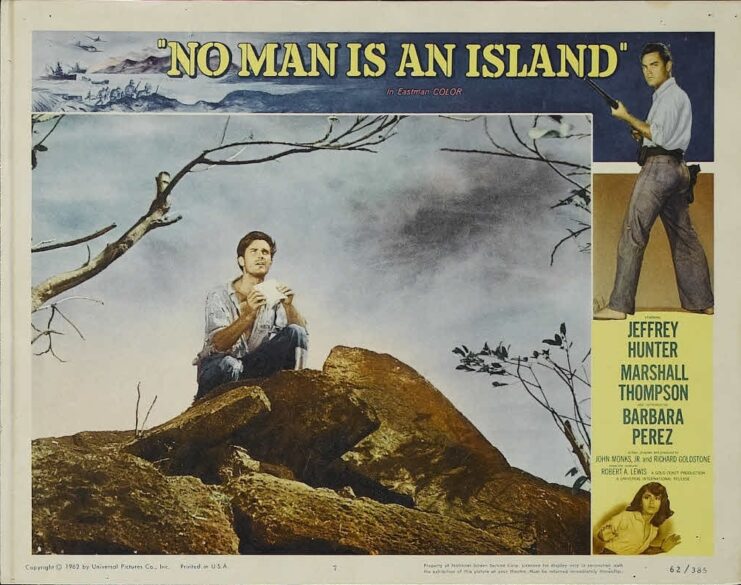

George Ray Tweed retired from the US Navy as a lieutenant in 1948, and he passed away in 1989. Prior to his death, he’d become a best-selling author for his book, Robinson Crusoe, U.S.N: The Adventures of George R. Tweed, Rm1 on Japanese-Held Guam. He also had his story portrayed in the 1962 film, No Man Is an Island, starring Jeffrey Hunter.