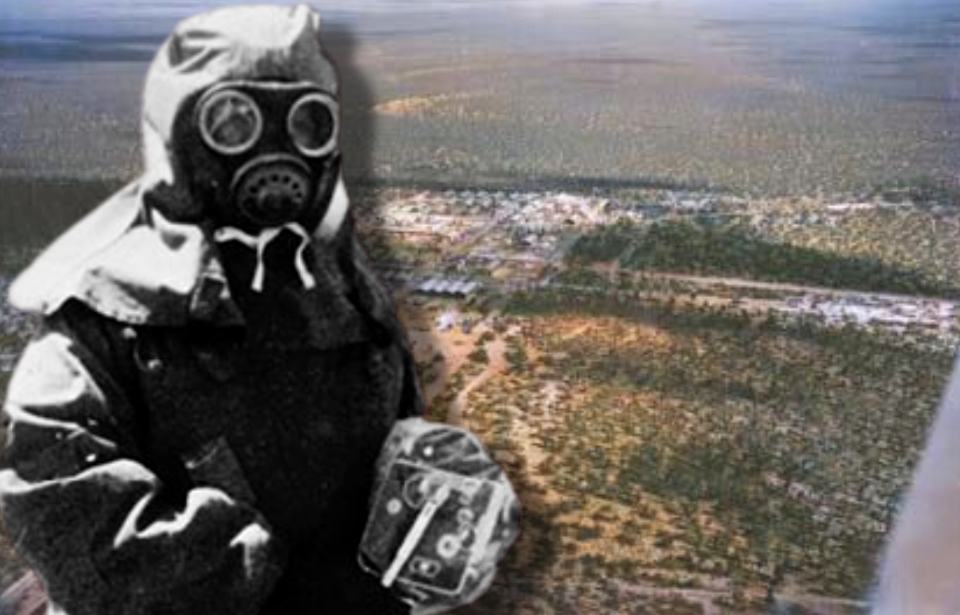

At the end of World War II, atomic arsenals began to emerge, notably in Britain. To improve its nuclear technology, the UK turned to Australia to carry out trials in its isolated bushland. Although Australia granted the United Kingdom permission, the lasting impact of these nuclear tests on the Outback remains evident even seven decades later.

British nuclear tests in the Australian Outback

Between the 1950s and ’60s, Britain conducted 12 nuclear tests in Australia, along with hundreds of smaller trials. Seven tests took place in Maralinga, a remote region in South Australia’s Great Victoria Desert, aimed at evaluating the performance and safety of the nuclear technology being developed.

The primary tests were known as Operation Buffalo and Operation Antler. While these two were the most significant trials, the smaller tests are reported to have caused greater nuclear contamination. Some of these tests produced mushroom clouds that soared to 47,000 feet, with radioactive fallout reaching as far as the city of Townsville.

The most severe testing took place in 1960, ’61 and ’63 as part of the Vixen B trials at the Taranaki site. These British nuclear tests were designed to examine the effects of fire on nuclear weapons, leading to the release of more than 40 kg of uranium and 22.2 kg of plutonium.

In comparison, the atomic bombs dropped on Japan during World War II – Little Boy and Fat Man – contained 64 kg of uranium and 6.4 kg of plutonium, respectively.

Cleaning up the Australian Outback after the nuclear tests

Britain concluded its nuclear testing in the Australian Outback in 1963, following the signing of the United Nations Partial Ban Treaty by both nations. Cleanup efforts began in 1967, with contaminated materials buried in trenches sealed with concrete. After British physicist Noah Pearce’s report was published in 1968, Australia absolved Britain of further liability at Maralinga—though we now know that the report was flawed.

The full extent of the nuclear tests wasn’t uncovered until 1984, amid increasing public scrutiny. A 1984-85 Royal Commission report revealed that the site still posed “significant radiation hazards” and criticized Australia’s oversight of the trials’ safety, particularly regarding the impact on the Indigenous population in the area.

Although the Tjarutja people were granted native title to the land in 1985, a thorough, large-scale cleanup didn’t occur until a decade later. The Australian government spent five years completing the task, with the final cost exceeding $170 million. Britain agreed to contribute to the expenses on an ex gratia basis, offering €20 million in 1993.

By 2000, all but 120 square kilometers of the roughly 3,200 square kilometers were deemed safe for unrestricted access.

Radiation concerns still remain

The Maralinga Rehabilitation Technical Advisory Panel (MARTAC) reported in the early 2000s that the plutonium contamination at the Taranaki site had been incorrect by a factor of 10. They wrote, “A comparison between the levels reported by the U.K. at the time and the field results reported by the Australian Radiation Laboratory […] demonstrates an underestimate of the plutonium contamination about an order of magnitude.”

Recent research conducted by Melbourne’s Monash University found that “hot particles” still exist in the soil. These are microscopic remnants of uranium and plutonium, which, due to the harsh environment of the Australian Outback, are slowly releasing plutonium into the soil and groundwater.

The chemicals present are between a few micrometers and nanometers in size. Some have created “a plutonium-uranium-carbon compound that would be destroyed quickly in the presence of air, but which has held stable by [an iron-aluminum] alloy.” These chemicals are likely the result of the cooling of molten metal droplets from the initial nuclear explosions.

Researchers found the plutonium has resulted in the continued release of radiation into the environment, where it’s absorbed and ingested by humans, animals and plant life. While more research is needed regarding the breakdown of these particles and the impact of weather on their release, the study overall is a guide for environmental protection.

The contamination has caused long-term health effects

Those residing in the area of the Australian Outback where the nuclear tests were conducted complain of the health effects they’ve suffered due to the plutonium contamination. Experts say long-term exposure to plutonium-emitted alpha radiation can cause many issues, including DNA damage, lung cancer and radiation sickness.

Such exposure isn’t absorbed through the skin. It occurs through breathing, eating and drinking contaminated material, meaning those affected are likely getting it from local resources.

Since they were granted access to the land again, the local Indigenous people have faced numerous emotional, social and physical hardships. Food grown near the site is too dangerous to consume, and many find plants are unable to survive in the now-sterile soil. They hope the study will allow for support measures to be put in place to not only protect the environment, but also address the health issues they face.

More from us: The Nuclear War Between Russia and China That Almost Happened

Want War History Online‘s content sent directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter here!

While the Australian government agreed in 2017 to provide increased healthcare for Indigenous people and veterans affected by the nuclear testing conducted at Maralinga, more is needed to ensure the land becomes safe for future habitation and use.