Japan’s surrender in World War II marked the end of one of the most destructive and challenging periods in history. Germany had already surrendered in May 1945, but Japan continued to fight for a few more months before finally giving in. While many believe the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were the main reason Japan surrendered, other major events also influenced the decision.

Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Two key events that led to Japan’s surrender were the atomic bombings on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. On the morning of August 6, 1945, the former was subjected to an attack that decimated the city and inflicted a devastating human toll, with between 90,000-146,000 killed both during Little Boy‘s detonation and after, due to the effects of radiation exposure and burns to the skin.

Just three days later, on August 9, Nagasaki experienced a similar fate, with the Boeing B-29 Superfortress Bockscar dropping the atomic bomb Fat Man on the city, located some 261 miles from Hiroshima. Just like the latter, Nagasaki suffered extensive losses, with between 60,000-80,000 citizens perishing within four months of the attack.

Between both detonations, it’s estimated around 129,000-226,000 people lost their lives – a truly devastating number.

The atomic bombs not only demonstrated the US military’s superiority, but also signaled the emergence of a new and terrifying era in warfare. The realization that further nuclear attacks could obliterate Japanese cities forced leadership to reconsider their position; the fear of additional devastation, coupled with the understanding that conventional defenses were futile against such power, significantly influenced Japan’s decision to surrender.

Declaration of war by the Soviet Union

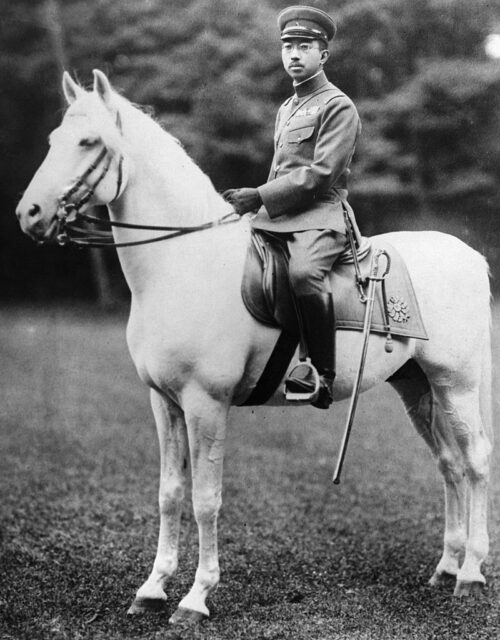

The impact of the atomic bombings was intensified by the Soviet Union’s declaration of war on Japan on August 8, 1945, delivering a decisive blow to the already dim prospects of the Japanese military. Japanese leaders had underestimated the threat posed by the Red Army, assuming they would not face Soviet forces until the spring of 1946. Emperor Hirohito had even sought assistance from Joseph Stalin, hoping he could help mediate between Japan and the United States.

The sudden Soviet invasion of Manchuria caught Japan off guard, leading to 650 of the 850 occupying troops being killed or wounded within the first two days of fighting. This unforeseen attack killed any lingering hopes for a negotiated peace and showed Japan’s growing geopolitical isolation.

Faced with the grim reality of a two-front war, Japan’s political and military leaders realized their position was unlikely to hold, prompting even Emperor Hirohito to encourage them to reconsider surrender.

Japan’s military resources were beginning to dwindle

By 1945, Japan was in a dire situation. Years of intense fighting had greatly weakened its military, largely due to relentless American attacks. The U.S. strategic island-hopping campaign had effectively cut Japan off from its occupied territories in the Pacific. On top of that, a strict naval blockade and relentless aerial bombing campaigns targeted Japanese cities and industries, crippling the country’s ability to continue the war.

With critical resources running low, life became extremely difficult for the Japanese people. Food and fuel shortages were severe, and the average civilian’s daily calorie intake dropped to just 1,680. Meanwhile, most able-bodied men had already been drafted into the military, leaving the nation with few remaining defenders.

Realizing that victory was no longer possible under these conditions, Japan’s leaders ultimately decided to surrender.

Japan wanted to preserve its Emperor system

A key part of Japan’s surrender talks was the insistence on keeping the emperor system. The Japanese government made it clear that giving up the monarchy was not an option. Leaders were afraid that an unconditional surrender might mean removing the emperor entirely, which heavily influenced their decision-making.

Eventually, this led to what’s known as the “Humanity Declaration,” in which Emperor Hirohito agreed to stay on as a symbolic figure. This meant he was no longer viewed as a god but instead as “the symbol of the State and of the unity of the people.”

Simply put, the emperor would still represent the country, but he wouldn’t have any real political power. A new constitution would be introduced to reflect these changes.

Facilitating Japan’s surrender

The process of facilitating Japan’s surrender was marked by significant diplomatic and communicative efforts. Behind the scenes, diplomats and intermediaries worked tirelessly to establish a channel of communication between Japan and the Allied forces. These efforts were aimed at finding a mutually acceptable solution that would allow the country to surrender while addressing the concerns of all parties involved.

With all the aforementioned factors piling on top of the each other, the decision was ultimately made for Japan to surrender, with Emperor Hirohito announcing the news to the public via a radio broadcast on August 15, 1945.

The first time he’d spoken to average citizens directly, the emperor explained, “The war has lasted for nearly four years. Despite the best that has been done by everyone – the gallant fighting of the military and naval forces, the diligence and assiduity of our servants of the state, and the devoted service of our one hundred million people – the war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan’s advantage, while the general trends of the world have turned against her interest.”

More from us: Paul Tibbets Dropped the Atomic Bomb on Hiroshima and Was Given No Funeral or Gravestone

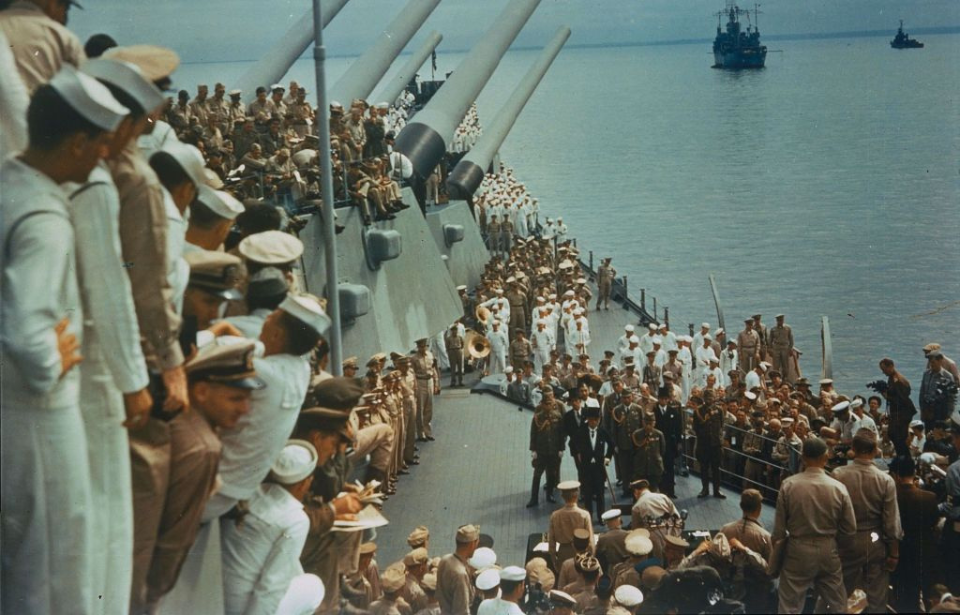

Just over two weeks later, aboard the American battleship USS Missouri (BB-63), the Japanese Instrument of Surrender was signed. Those present included representatives from the Empire of Japan and the Allied nations, with the most notable being Gen. Douglas MacArthur, Fleet Adm. Chester Nimitz and Chief of the Japanese Army General Staff Gen. Yoshijirō Umezu.