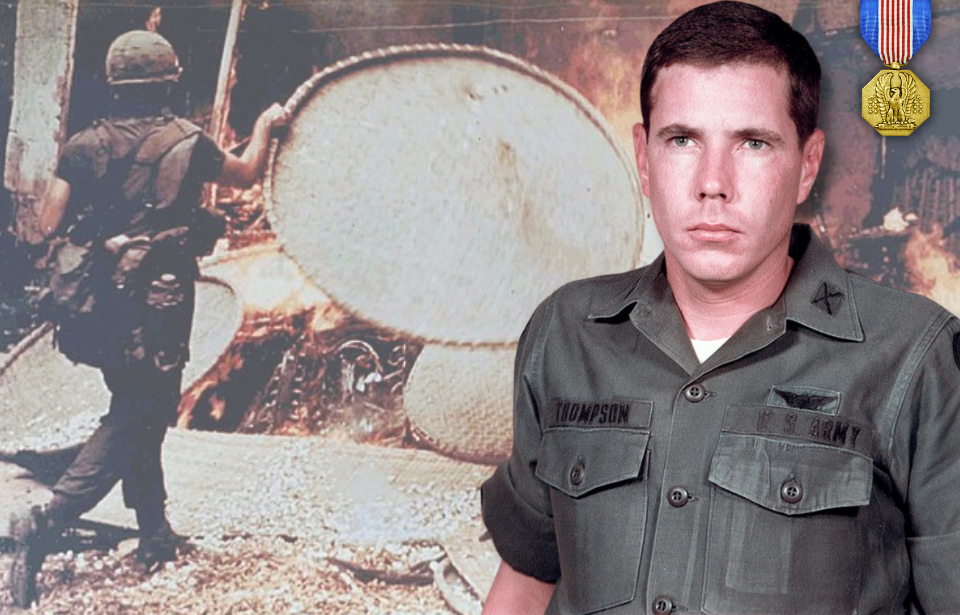

During the Vietnam War, the US military used several controversial tactics in the name of safeguarding the American public. One of the most tragic events of this time was the Mỹ Lai Massacre on March 16, 1968, when US Army soldiers killed hundreds of innocent Vietnamese civilians. The death toll could have been even greater if not for the brave actions of Chief Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson, Jr. and his helicopter crew, who stepped in to stop the killing.

Hugh Thompson Jr.’s entry into the US military

Hugh Thompson, Jr. was born on April 15, 1943, in Atlanta, Georgia, to a US Navy veteran who had served in World War II. His brother, like Hugh, would also serve in Vietnam, deployed with the US Air Force.

In 1946, the family relocated to Stone Mountain, Georgia, where Thompson became involved in the Boy Scouts of America. His parents emphasized maturity, discipline, and a strong sense of justice, reinforcing their values by speaking out against racism and supporting ethnic minorities in their community.

As a teenager, Thompson worked at a funeral home and plowed fields. After graduating from Stone Mountain High School in 1961, he enlisted in the Navy, serving as a heavy equipment operator in a naval mobile construction battalion at Naval Air Station Atlanta (now the General Lucius D. Clay National Guard Center). He was honorably discharged in 1964 and returned to Stone Mountain to begin a family.

Returning to service during the Vietnam War

When the Vietnam War began, Hugh Thompson Jr. was working as a licensed funeral director, having studied mortuary science. Despite being discharged from the military, he felt it was his obligation to serve alongside his fellow countrymen and enlisted in the US Army.

Prior to being deployed, Thompson completed the Warrant Officer Flight Program at both Fort Wolters, Texas and Fort Rucker, Alabama. In December 1967, he made his way to Vietnam as part of Company B, 123rd Aviation Battalion, 23rd Infantry Division.

Mỹ Lai Massacre – four hours of terror

On March 16, 1968, Hugh Thompson Jr. and his Hiller OH-23 Raven crew, Crew Chief Glenn Andreotta and Gunner Lawrence Colburn, were ordered to travel to Mỹ Lai, Sơn Mỹ, Sơn Tịnh district, Quảng Ngãi province, South Vietnam to support a search and destroy operation being undertaken by Task Force Barker. Nicknamed “Pinkville” by the American forces, the hamlet was believed to be a Viet Cong stronghold, despite its population being primarily comprised of rice-farming families.

At approximately 7:24 AM and continuing for four hours, 100 men from Company C, 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry Regiment, 11th Brigade, 23rd Infantry Division, and 100 from Company B, 4th Battalion, 3rd Infantry Regiment, 11th Brigade, 23rd (Americal) Infantry Division began shelling Mỹ Lai. Thompson’s OH-23 and other reconnaissance aircraft flew overhead, but suffered no enemy fire – and neither did the forces on the ground.

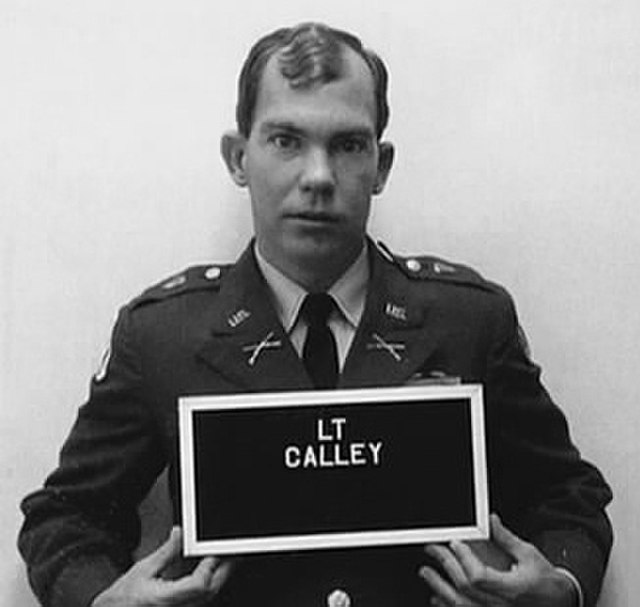

Upon entering the village, the members of Company C began rounding up and murdering civilians, going so far as to sexually assault women and set their huts on fire. In one of the more horrific incidents to occur during the massacre, the men of 1st Platoon, commanded by Second Lt. William Calley, rounded up 70-80 villagers into an irrigation ditch and killed them with grenades, machine gun fire, knives and bayonets.

Hugh Thompson Jr. and his helicopter crew intervene

Flying overhead, Hugh Thompson Jr. and his OH-23 crew began to suspect something was wrong with the scene below, with him telling radio station KPFK in Los Angeles decades later, “We started thinking what might have happened, but you didn’t want to accept that thought because if you accepted it, that means your fellow Americans, people you were there to protect, were doing something very evil.”

Thompson’s suspicions were confirmed when he witnessed Capt. Ernest Medina, who’d led the ground forces into Mỹ Lai, kill a wounded and unarmed woman. The helicopter pilot then noticed the irrigation ditch filled with deceased civilians. When he confronted Calley about the dead, the second lieutenant simply responded that he was just “following orders.”

In disbelief, Thompson, Andreotta and Colburn took to the air to search for civilians they could evacuate. They spotted a group of children, elderly men and women who were being pursued by a platoon. Thompson landed his OH-23 and ordered his crewmen to point their guns at the advancing American soldiers while he tried to persuade the Vietnamese civilians to follow him to a safer location.

Eventually, the helicopter began to run low on fuel. After transporting an injured child to hospital, Thompson flew to Landing Zone Dottie, the headquarters for Task Force Barker, and reported what he’d witnessed to his superiors. This prompted Lt. Col. Frank Barker to radio the ground forces to halt the massacre, with Medina telling his mean to “cut [the killing] out – knock it off.” After this, Thompson and his crew returned to Mỹ Lai to ensure the wounded had been evacuated.

Known as the “Mỹ Lai Massacre,” the event is considered “the most shocking episode of the Vietnam War” and was the largest publicized massacre of civilians by American forces during the 20th century. While US numbers place the total dead at 347, the Vietnamese state the amount is closer to 504.

The US Army tried and failed to cover up what happened

At 11:00 AM on the day of the massacre, Hugh Thompson Jr. filed an official report, which led senior officials to cancel similar operations that were planned against other villages in Quảng Ngãi province.

Initially, the US Army tried to frame what had happened as a victory against the Viet Cong, with initial reports claiming “128 Viet Cong and 22 civilians” had been killed during a “fierce fire fight.” Thompson was even awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his actions on March 16, 1968, but he threw the citation away, as it presented a fabricated version of events.

It wasn’t until November 1969 that the true nature of the Mỹ Lai Massacre became known to the public, when journalist Seymour Hersh published an interview with Specialist 5 Ron Ridenhour. A door gunner in Vietnam, Ridenhour relayed what he’d been told by members of Company C, adding that he’d previously appealed to the Pentagon, Congress and the White House to address what had happened.

Around this time, Thompson was summoned to appear before a special closed hearing by the House Armed Services Committee, during which he was criticized by Congressmen who tried and failed to have him court-martialed. Following Ridenhour’s revelations, a military commission investigated the massacre and found there to be widespread failures in Task Force Barker’s leadership, morale and discipline.

William Calley was the only one convicted for his actions in Mỹ Lai

In 1970, 26 officers and enlisted soldiers, including Ernest Medina and William Calley, were charged with numerous criminal offenses in relation to the Mỹ Lai Massacre. Hugh Thompson Jr. testified against the defendants, of whom only Calley was convicted. At the end of the trial, the second lieutenant was found guilty of murdering 22 civilians. Initially given a life sentence, he only wound up serving three-and-a-half years under house arrest after President Richard Nixon commuted his sentence.

While there was overwhelming evidence to show Calley was personally responsible for the deaths of numerous civilians, a survey found that four out of five Americans disagreed with the verdict. In fact, within three months of him being found guilty, the White House received over 300,000 telegrams and letters, with Calley himself the recipient of 10,000 packages and letters a day.

Thompson, on the other hand, was seen as a traitor by both the American public and Army personnel, who were upset at his testimony. He frequently received death threats, with the negative attention causing him to suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), severe nightmare disorder and alcoholism. The stress over Calley’s conviction also led him and his wife, Palma Baughman, to divorce.

Hugh Thompson Jr.’s military service following the Mỹ Lai Massacre

Hugh Thompson Jr. continued to serve in Vietnam following the Mỹ Lai Massacre, flying numerous observation missions. He was hit by enemy fire a total of eight times, losing his helicopter on four different occasions. In the final incident, he was brought down by machine gun fire and broke his back in the crash. This ended his combat career in Vietnam.

Following his rehabilitation, Thompson was assigned to Fort Rucker, where he served as a pilot instructor, as well as Fort Jackson, South Carolina; bases in Hawaii; Fort Hood, Texas; South Korea; and Fort Ord, California. He later received a direct commission, and retired in 1983 with the rank of major.

Hugh Thompson Jr.’s later life and death

Following his retirement, Hugh Thompson Jr. became a helicopter pilot for the oil industry in the Gulf of Mexico. Following the release of the documentary Four Hours in My Lai and the book of the same name, the Army veteran found himself the subject of a campaign to have his heroism and that of his crew recognized. A number of politicians and military officials supported the movement, including President George H.W. Bush.

In 1998, Thompson, Colburn and Andreotta were awarded the Soldier’s Medal, the Army’s highest award for bravery not involving direct contact with the enemy. That same year, he traveled to Mỹ Lai to visit with the civilians he’d saved during the massacre. Speaking with CNN at the time, he said, “Something terrible happened here 30 years ago today. I cannot explain why it happened. I just wish our crew that day could have helped more people than we did.”

Today, a memorial stands in the South Vietnamese hamlet, in honor of Thompson and those who lost their lives on March 16, 1968.

More from us: Despite Being up Against 2,000 Enemy Troops, Bernard Fisher Risked His Life to Save a Fellow Airman

Want War History Online‘s content sent directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter here!

Following his work in the Gulf of Mexico, Thompson served as a counselor with the Louisiana Department of Veterans Affairs. On January 6, 2006, after treatment for cancer, the 62-year-old was taken off life support and passed away at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Pineville, Louisiana. He was buried in Lafayette with full military honors.