In August 1945, the United States dropped two atomic bombs on Japan, marking the only time in history that nuclear weapons have been used in conflict. The destruction caused by these devices was catastrophic – and a third bomb was set to be dropped. Fortunately, Japan surrendered just days before it could be used, saving tens of thousands of lives.

While this explosive didn’t claim any lives, its plutonium core later tragically resulted in the deaths of two US physicists, earning it the ominous nickname, “Demon Core.”

A third bomb

It’s easy to assume the Manhattan Project, the American program designed to produce atomic weapons, was always intended to develop only two bombs. However, this wasn’t the case. The project evolved into a comprehensive production line for atomic weapons. Most of the resources in this multi-billion dollar effort were dedicated to acquiring enriched uranium and plutonium, which were particularly difficult to produce at the time.

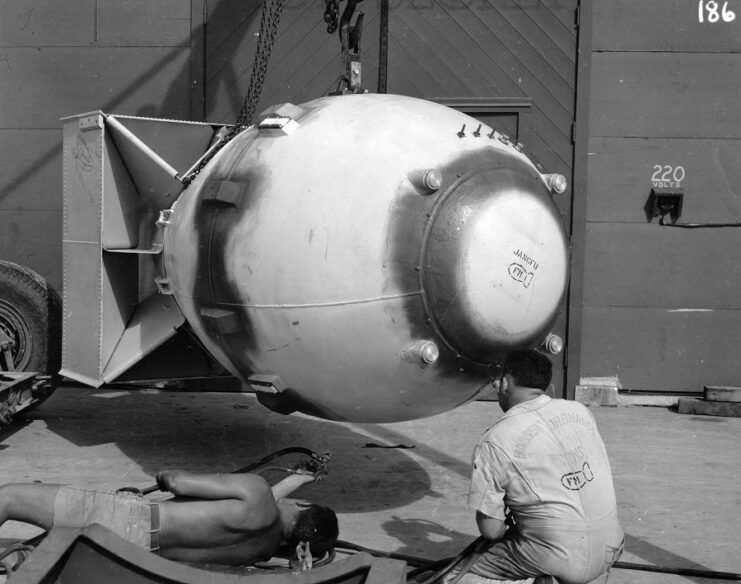

By summer 1945, the project had generated enough material for three bombs, with a fourth in development. This was earmarked for the Trinity Test, as well as the deployment of the Little Boy and Fat Man bombs. Japan didn’t surrender immediately after the two were dropped, prompting the US military to prepare a third, which was scheduled for release on August 19.

However, Japan surrendered on August 16.

At that time, few involved in the Manhattan Project expected such a limited number of bombs to be used. Many believed more would be necessary to compel Japan to surrender, and there were concerns that even if they did surrender, the war could easily resume. Ultimately, the third device was never used, leaving the US with its 6.2 kg, nine-cm wide plutonium core. It was later repurposed for testing and incorporated into other projects.

Demon Core

One notable experiment aimed to determine the core’s criticality – the stage at which the fissionable material can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. During these tests, scientists partially surrounded the core with neutron reflectors, which redirected neutrons back into the core, amplifying the reaction.

Had the core been fully surrounded by neutron reflectors, it would have rapidly achieved supercriticality, resulting in a huge burst of radiation.

The safety protocols at the time were alarmingly lax, permitting scientists to conduct these experiments manually.

First accident

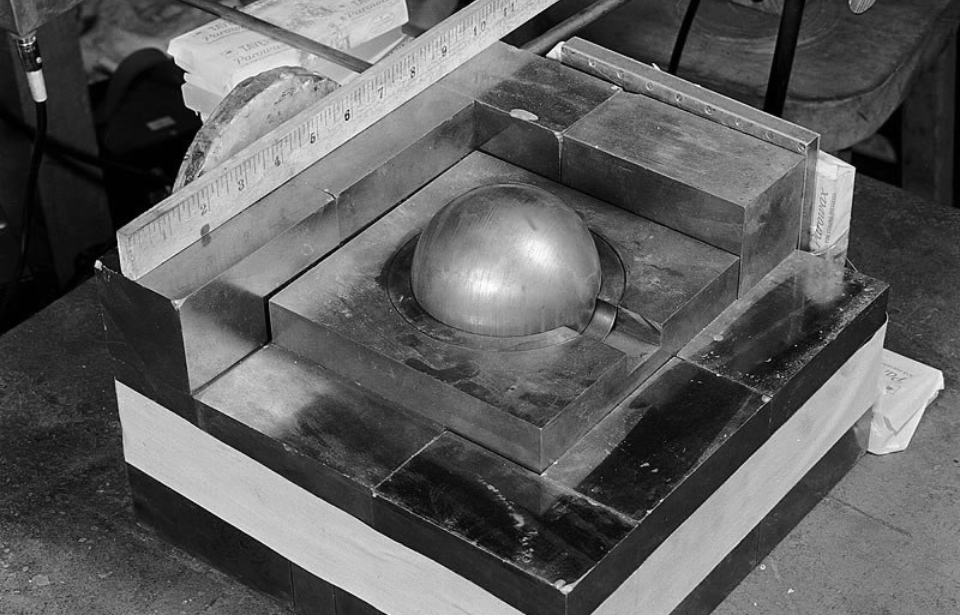

Physicist Harry Daghlian was performing this experiment in 1945 when it went fatally wrong. He was placing neutron-reflecting tungsten carbide blocks around the core to bring it closer to criticality when he accidentally dropped one of the blocks onto the core. Daghlian removed the block as fast as he could but it was too late. In that brief moment, the core entered super criticality and released a lethal amount of radiation.

Daghlian spent the next three weeks battling radiation sickness before finally passing away. After Daghlian’s death, much stricter safety protocols were brought in to prevent it from happening again.

The following year one of Daghlian’s colleagues, Louis Slotin, took over the experiments. Slotin was a brilliant physicist but was known to disregard safety.

Slotin’s experiments with the core were similar to Daghlian’s but this time two half-sphere neutron reflectors would be slowly closed around the core to increase the core’s activity. However, to prevent another accident, metal spacers were placed between the half spheres to stop them from enclosing the core fully.

Second incident

Quite the risk-taker, Slotin ignored the protocol and did away with the spacers, using his own method instead. His method was faster but was also much more dangerous. Slotin would use a simple flathead screwdriver to maintain the gap between the reflectors, adjusting it by hand as necessary. He became quite proficient at this technique and became known among his colleagues for “tickling the dragon’s tail,” as it was called at the time.

Slotin’s colleagues were aware that this technique was extremely risky, and even tried to warn him, but he continued anyway.

On May 21, 1946, Slotin was performing the experiment in front of a small group of people in a Los Alamos laboratory. Using his usual technique, he lowered the two neutron reflecting half-spheres around the core, using the screwdriver to keep them from fully closing.

However, on this occasion, the screwdriver slipped by a tiny amount, allowing the two neutron reflectors to completely enclose the core. The core immediately entered super criticality, emitting a bright blue flash of light and a powerful blast of radiation.

End of the ‘Demon Core’

Slotin quickly removed the neutron reflectors, but like Daghlian, the damage was already done. He had been showered by an extremely high dose of radiation. As he was leaning over the core at the moment the accident happened, he absorbed much of the radiation, likely saving the lives of the others in the room.

Within minutes of the accident, Slotin was already showing signs of radiation poisoning. He died just 9 days later.

New! Want to become a trivia master? Sign up for our War History Fact of the Day newsletter!

After the plutonium sphere claimed two lives, it became known as the “demon core.” It was meant to be used Operation Crossroads nuclear tests, but this never happened and it was eventually melted down and recycled into other cores.