Just after 11:00 AM on July 19, 1918, the USS San Diego (ACR-6), originally called the USS California, was hit by a powerful explosion on her port side, close to the port engine room. Within half an hour, she had settled on the floor of the Atlantic Ocean.

For nearly a century, the cause of the catastrophe was unknown, fueling considerable debate among historians. A century later, however, an underwater archaeologist uncovered a new crucial piece of evidence.

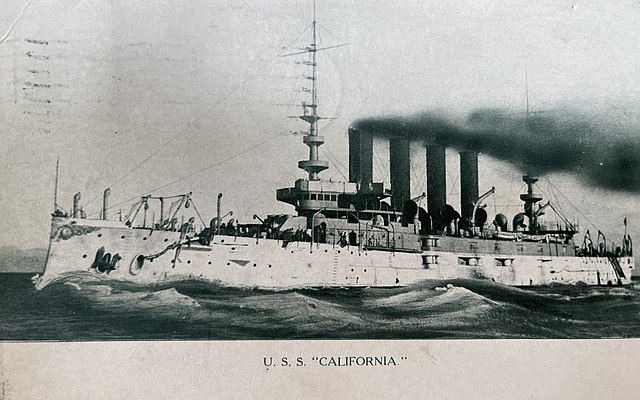

Service as the USS California

The USS California was launched on April 28, 1904, and commissioned just over three years later. It was assigned to the 2nd Division of the Pacific Fleet, where it participated in various exercises and drills along the West Coast.

By March 1912, the California had become part of the Asiatic Station, a fleet of US Navy vessels stationed in East Asia. During this period, the ship safeguarded American interests in Nicaragua, maintained a military presence off the coast of Mexico, and helped sustain peace amidst political unrest.

In 1914, the armored cruiser was renamed the USS San Diego.

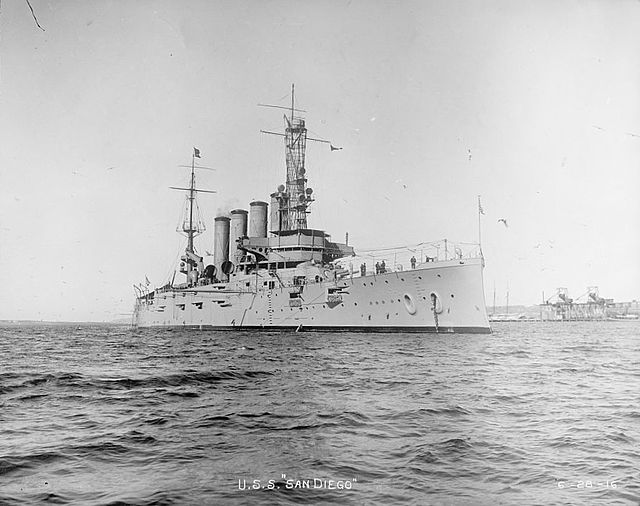

Renamed the USS San Diego (ACR-6)

The following year, the USS San Diego was put on reduced commission after a boiler explosion – a hint at future troubles. She resumed duty as the flagship for the Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Fleet, until February 1917, when she was put in reserve until the United States entered World War I that April.

One day after the US declared war on Germany, San Diego was fully commissioned as the flagship of the Commander, Patrol Force, Pacific Fleet. On July 18, she was ordered to join the Atlantic Fleet, tasked with escorting convoys through the perilous ocean routes to Europe, where the North Atlantic was heavily infested with U-boats.

Exactly one year later, she encountered the full dangers of the ocean.

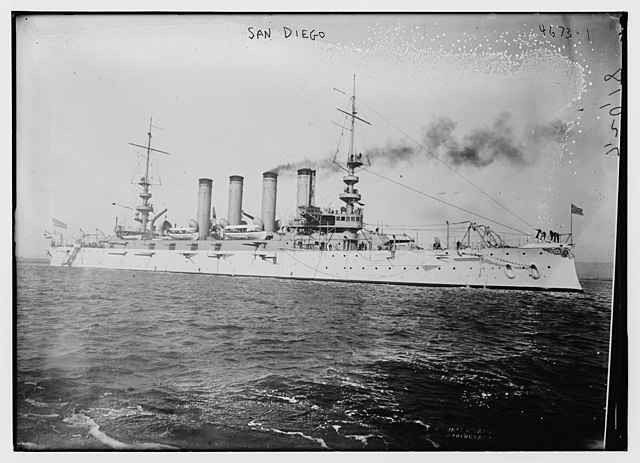

Shaken by an explosion at-sea

On July 18, 1918, the USS San Diego set out from the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Maine, bound for New York, with Harley H. Christy in command. During the journey, the crew remained on high alert; lookouts, fire control teams, and gun crews stayed vigilant as the ship followed a zigzag course.

The following morning, a powerful explosion hit the port side of the ship. The crew acted quickly to stop the San Diego from flooding, but they encountered a major obstacle: the blast had distorted the bulkhead, preventing the watertight door between the engine room and the No. 8 fireroom from sealing.

Sinking of the USS San Diego (ACR-6)

As the flooding continued, Capt. Christy ordered the ship to proceed full speed ahead, anticipating they were under attack by a German U-boat. Not only was the USS San Diego unable to accelerate, she could barely move at all – both engines were disabled and her machinery compartments were filling with water.

San Diego began to list, and, within 10 minutes of the explosion, was sinking. Christy ordered his crew to lower the lifeboats and abandon ship, and, within 28 minutes, the cruiser was at the bottom of the Atlantic, making her the only major American warship lost during World War I.

Of the over-1,000 crewmen onboard, six died in the tragic incident.

Survivors were left with no answers

After the sinking, Capt. Christy remained convinced they’d been struck by a torpedo, but there was no evidence that a U-boat had been in the area at the time, and none of the lookouts saw the wake created when a torpedo is fired.

Others speculated it could have been a sea mine, but it’s unlikely one would explode at the stern, instead of the bow of the ship. An official inquiry concluded the sinking was caused by such an explosive, as six contact mines had been located in the vicinity, but the true reason wasn’t that simple.

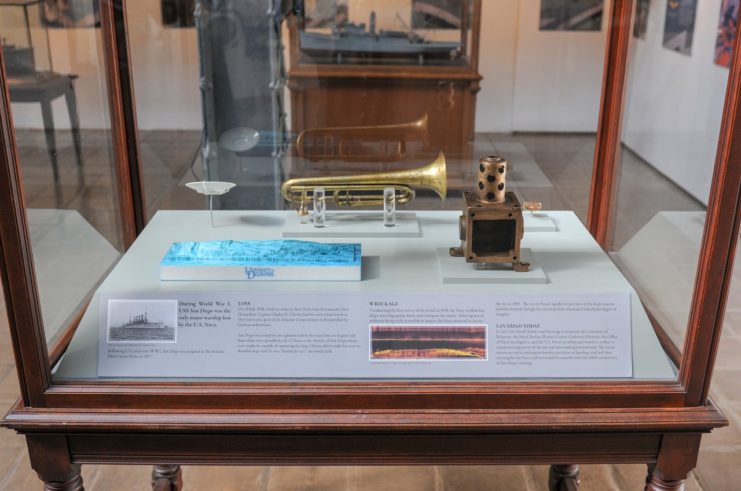

In 2018, 100 years after the USS San Diego sank, USNI News announced that the cause of the explosion was still inconclusive. Luckily, the American Geophysical Union (AGU) was about ready to hold its annual conference, where a bombshell revelation a century in the making would be dropped.

What really happened to the USS San Diego (ACR-6)?

After two years of research using archival documents, 3D scans and high-tech models, a team of researchers from the Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC) announced their findings. At the 2018 AGU conference, underwater archaeologist Alexis Catsmabis declared, “We believe that U-156 sunk San Diego.”

Catsmabis explained that the flooding patterns didn’t look like an explosion was set inside the vessel, and the hole ripped into the USS San Diego‘s hull “didn’t look like a torpedo strike,” either. It was concluded that the armored cruiser was struck by a U-boat mine placed by SM U-156.

“Torpedos of the time carried more explosives than mines – and would have shown more immediate damage,” shared marine scientist Arthur Trembanis. The explosion itself wasn’t that powerful, but San Diego was filled to the brim with coal, making her top-heavy enough to easily capsize as she took on water.

“With this project, we had an opportunity to set the story straight,” Catsmabis said in a press release, “and by doing so, honor [the memory of the six crewmen who died] and also validate the fact that the men onboard did everything right in the lead up to the attack as well as in the response.”

Are you a fan of all things ships and submarines? If so, subscribe to our Daily Warships newsletter!

Today, the wreck of San Diego lies upside down off the coast of New York’s Fire Island, some 110 feet below the water’s surface. Since the highest parts are just 66 feet down, the wreck has become a popular scuba diving attraction. It’s also been nicknamed the “Lobster Hotel” for the large community of lobsters that call the armored cruiser home.